More than half of the United States is underwater: a sunken landscape of canyons, volcanic ranges, coral reefs, and kelp forests.

That’s been true since 1983, when then-President Reagan proclaimed national sovereignty over the ocean within 200 miles of the coastline, and banned foreign fishing fleets from fishing them.

The Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, which provides guidelines for the management of U.S. fisheries by eight regional councils, aims to protect species from overfishing so the U.S. can derive the maximum economic benefit from them year to year. That mandate doesn’t always fit with conservation goals, which are pursued through a matrix of federal agencies and programs that work with, and sometimes parallel to, the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

This level of bureaucracy makes for many acronyms and little action. It’s just one respect in which marine conservation in the U.S. remains murky. There’s wide acknowledgement of the vulnerability of marine ecosystems in an ocean that’s rapidly warming and acidifying, but the collective will to enact protective measures in the ocean is often lacking.

Compromise and conflict between environmental and commercial fishing interests leads to slow implementation of urgently needed protection, and creates hurdles for research and enforcement in protected areas. And under the Trump Administration, marine conservation—already a contentious project—has become politicized to an unprecedented degree.

“Significant hurdles”

As we’ve continued to burn fossil fuels and release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, the oceans have faced a triple threat: warming, acidification, and loss of oxygen. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report on the ocean and cryosphere states that since 1970, the oceans have absorbed roughly a third of carbon dioxide emissions, warming by a global average of one degree Celsius and becoming 30 percent more acidic. Marine heatwaves, which devastate kelp forests and coral reefs, have become far more frequent and intense.

Oxygen-depleted “dead zones,” caused by stagnating circulation and algal blooms, have ballooned in the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Northwest. In hot coastal waters, marine viruses and shell disease have decimated valuable American fisheries: abalone in Northern California, and lobster in southern New England. Meanwhile, acidification eats away at the mineralized shells of invertebrates and weakens reefs, and may also have complex physiological effects on fish.

Marine life has responded to these tumultuous changes by migrating, invading new ecosystems, or seeking refuge in deeper water.

Not all the damage is climate induced. Even in the U.S., where most fisheries are sustainably managed, low populations and winnowed biodiversity—the results of decades of industrial overfishing—have eroded the resiliency of marine species to climate change. The fragmentation of Atlantic cod populations in New England, to cite the most famous example of fishery failure under rigorous management, has made the fishery’s rebound in a warming environment an uphill battle.

Offshore drilling for oil and gas has long posed existential threats to marine ecosystems, but offshore wind and hydroelectric power, a growing industry, may also have a variety of unintended and poorly-understood effects on wildlife, particularly on animals that use sonar or electromagnetism to navigate.

To combat these emerging threats and impacts, marine protected areas, or MPAs, were developed as an ocean conservation tool in the 1990s. Their proponents argued that habitat in the oceans should be protected in the same way that national parks protect land, by blocking off large areas where disturbances to wildlife are minimized. The idea, bolstered by studies that showed creating marine reserves in biodiversity hotspots could help fisheries rebuild, gained traction internationally.

In 2010, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity set a target to place 10 percent of the world’s oceans in MPAs by 2020. The U.S., for its part, has surpassed that goal, putting 26 percent of its exclusive economic zone into MPAs. There are currently nearly 1,000 MPAs in the U.S., encompassing an area greater than Alaska, Texas, and California combined.

But not all of that space is protected equally, nor is it evenly distributed. Only 3 percent of U.S. waters are in “no-take” reserves that prohibit fishing, the most protective MPAs. Nearly all of those are in the remote marine national monuments around Hawaii and U.S. territories in the Pacific, established unilaterally under the Antiquities Act—far from the coast of the contiguous U.S., where most human-caused pressures are centered.

Commercial fishing gear can devastate marine life and habitat. The lines on lobster traps and crab pots can fatally entangle whales, and heavy bottom trawls and dredges disturb everything in their path on the seafloor, pulverizing corals and indiscriminately killing non-target species.

Marine sanctuaries, a type of MPA managed by the National Marine Sanctuaries Program under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), are designed through consultation and compromise with many users of the environment and may permit commercial and recreational fishing, military exercises, dredging, and drilling—activities that fall within the jurisdiction of several different government agencies.

These MPAs have a much lower level of protection than national monuments do, even though there are many layers to their management.

James Lindholm, a professor of marine science and policy at California State University who used to work for the National Marine Sanctuaries Program, told EHN that it isn’t always clear “which legislation can be brought to bear on which issue in which location.” Given the program’s mandate to protect biodiversity, it would try to create no-take research reserves within sanctuaries, “only to hit significant hurdles from NOAA Fisheries, because of Magnuson and its charge.”

“Protected areas that aren’t closed to fishing have a role to play,” Peter Auster, a fish ecologist at the University of Connecticut, told EHN. “But I think the general public thinks that a place that’s called a sanctuary actually protects everything.”

Even MPAs with high levels of protection are only effective if people follow the rules, a big “if” in remote parts of the ocean. “The ugly underside is when you talk about enforcement, which then becomes a different challenge altogether,” said Lindholm.

One example is the Oculina Bank, a limestone ridge off Florida’s east coast that hosts slow-growing deep-sea corals. Recognizing the reef’s importance as a spawning ground for grouper, bottom fishing was prohibited in 1984. Without enforcement, however, rock shrimpers continued to trawl illegally. When scientists visited the reef in 2001, they found that 90 percent of corals had been destroyed.

“It was a wasteland,” Sandra Brooke, a deep-sea coral researcher at Florida State University’s Coastal and Marine Laboratory, told EHN.

Continuous monitoring is essential to make sure that protections in the ocean are having their desired effect. But getting a complete picture of conservation outcomes is a challenge. Lindholm, who is on a team that monitors the deep waters in California’s MPAs, said the most frustrating lack of data is from the commercial fisheries. Where a fisherman finds his catch is proprietary information, and any data that could reveal the identity and location of a fishing boat is off-limits to scientists.

There is even less information about recreational fishing, though recent studies have suggested that the activity has a greater impact on fish populations than managers acknowledge. In 2018, recreational anglers took an estimated 42 million fishing trips in Florida. Recreational fishermen don’t report their catches; instead, the National Marine Fisheries Service relies on surveys to estimate their landings.

This year, the quota for red snapper in the Gulf of Mexico is higher for recreational anglers than it is for commercial fishermen—and the recreational fishery is notorious for exceeding its limit, contributing to overfishing of the rebuilding stock.

“We’re bending over backwards to produce the best science we can about where things are,” said Lindholm. “But what we really need is equivalently detailed spatial resolution on the fishing effort so we can truly demonstrate the extent to which the effort interacts with ecosystems. And we don’t have anything like that.”

Essential fish habitat

The Endangered Species Act is the most powerful check on commercial fishing, but it leaves a large gray area where species that are not commercially fished are unprotected.

“Most regimes that support fisheries management do not directly address elements of biodiversity until species have become endangered,” said Auster.

Species that may be rare but aren’t endangered and aren’t commercially fished—for example, deep-sea corals—don’t have any legal protections. All the same, corals are irreparably damaged by trawls that drag along the ocean floor to scoop up bottom-dwelling fish and crustaceans. “These animals are hundreds to thousands of years old,” said Auster. “Once destroyed, they’re not going to recover in any meaningful period of time.”

In the case of corals, an argument can be made that in some places they provide habitat for commercially fished species, like orange roughy or grouper, and therefore constitute “essential fish habitat,” areas that commercially-fished species use for spawning, breeding, foraging, and migrating.

Essential fish habitat, designated by the eight councils that enforce the Magnuson-Stevens Act, is the legal bedrock for MPAs, but is just a prelude to actual conservation. On July 7, the Center for American Progress released a report reviewing the protected status of U.S. waters. They found that, although functionally the entire exclusive economic zone in the U.S. has been designated as essential fish habitat, only a small portion has any restrictions on fishing, and of those areas, 75 percent are only minimally protected.

The Councils are only required to in-state restrictions or protections for essential fish habitat if they deem it practicable to do so; many designations simply come with citations of actions that have already been taken to regulate fishing gear.

The Center for American Progress report calls the Councils’ distinction “toothless,” and advises that Congress amend the Magnuson-Stevens Act to require that essential fish habitat be protected in some way.

This isn’t a new complaint. In 2000, several environmental groups sued NOAA and the National Marine Fisheries Service on the grounds that they violated the National Environmental Policy Act by not adequately assessing the detrimental impacts of fishing to essential fish habitat.

They won the suit, sending the Councils back to the drawing board. “If fish could speak, they would be shouting for joy,” Phil Kline, the fisheries director for the American Oceans Campaign, said at the time of the settlement.

The shouts would have been premature. “NOAA hasn’t really held their feet to the fire,” Alison Rieser, environmental attorney and professor at the University of Hawaii, told EHN. The courts didn’t stipulate a timeframe for the Councils, and it took 14 years for the New England Fishery Management Council to amend its essential fish habitat designations. In the process it rolled back protections for nursery and spawning grounds for Atlantic cod.

Within essential fish habitat, “habitats of particular concern” are meant to focus conservation efforts on wetlands and marine sites that are especially vulnerable to human activity such as coastal pollution, development, or damage from fishing gear. In addition to informing gear restrictions and fisheries closures, the habitats of particular concern designation carries weight in negotiations between the Councils and other users of the environment, like coastal development and offshore energy.

But habitats of particular concern don’t necessarily come with formalized protections of their own. “Just designating these areas doesn’t do squat for them,” said Brooke. “There’s no automatic regulation that comes with any of these things.”

Troubled waters under Trump

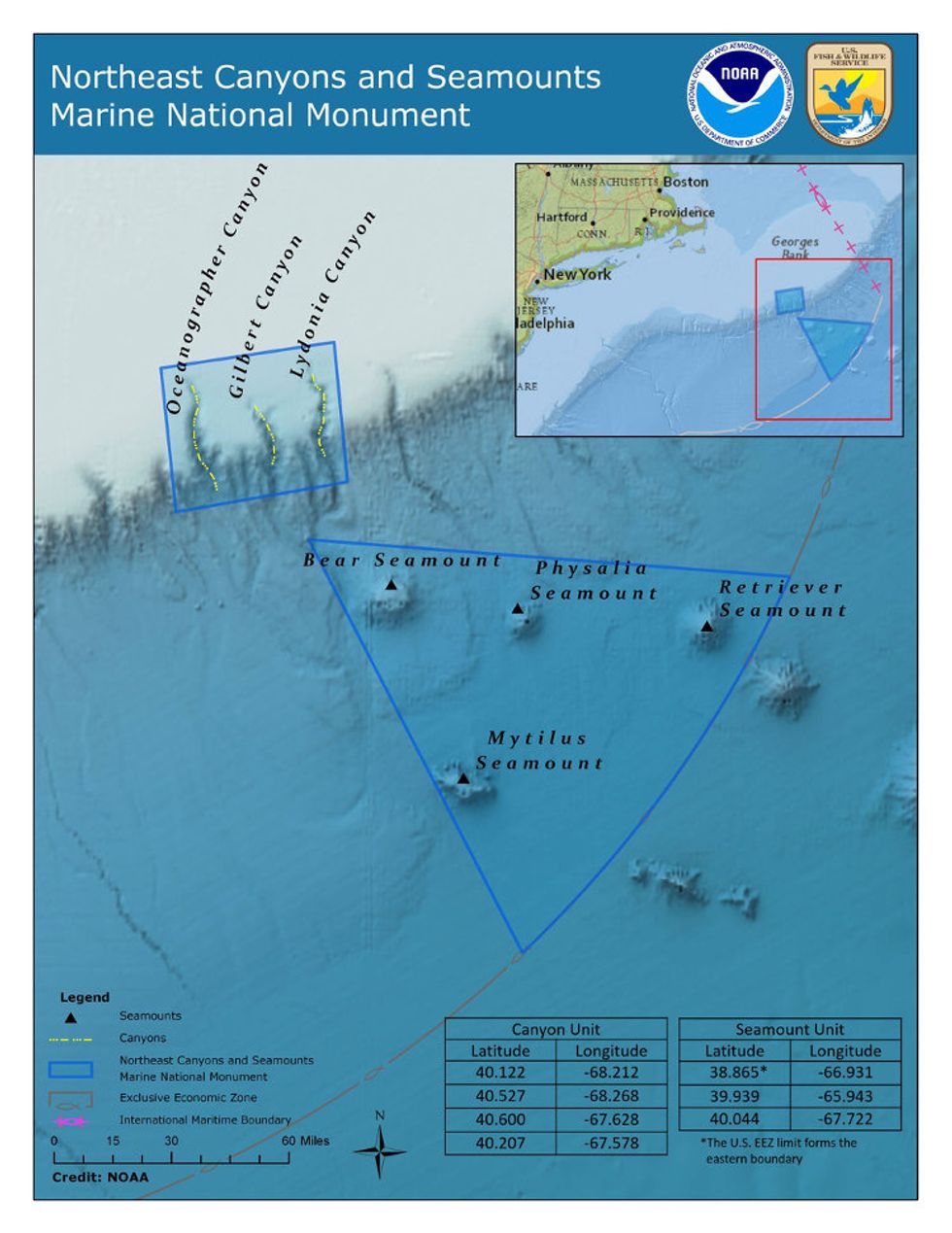

At the beginning of June, President Trump issued an executive order to open the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts National Monument to commercial fishing, chipping away at one of former President Obama’s last acts in office: the closure, in supposed perpetuity, of 5,000 square miles of ocean off the coast of Massachusetts.

The monument, straddling the edge of the continental shelf, is the only marine reserve on the Eastern Seaboard. The canyons and seamounts shelter 54 species of deep-sea corals and provide habitat to lobster, tuna, deep-diving beaked whales, and the now-critically endangered North Atlantic right whale.

“This would be the only place along the entire Eastern Seaboard that has no vertical lines for entangling marine mammals,” said Auster.

The Antiquities Act affords the president unilateral power to protect the ocean. Unlike conservation through restrictive management or multi-use sanctuaries, a national monument protects everything it encompasses.

It does not require a process of approval by stakeholders, which for sanctuaries can drag out for many years—time that is precious for ecosystems on the brink of collapse. That’s precisely why the Councils, while they haven’t taken a stance against the use of the Antiquities Act in the ocean, have lobbied to remove fishing restrictions from the marine national monuments, which together constitute more than 99 percent of all the highly protected marine habitat in the U.S. If there are going to be national monuments in the ocean, they argue, the fisheries within them should be managed with the same multi-stakeholder consensus that applies throughout the rest of federal waters.

“The ban on commercial fishing within Marine National Monument waters is a regulatory burden on domestic fisheries, requiring many of the affected American fishermen to travel outside U.S. waters with increased operational expenses and higher safety-at-sea risks,” wrote Regional Fishery Management Council representatives in a May letter to the Secretary of Commerce, Wilbur L. Ross Jr.

Though few boats fish in the northeast canyons, and none fish on the seamounts, control over the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts is a matter of principle, and precedent, for the New England Fishery Management Council. Shortly after Trump’s executive order in June, the Council created a deep-sea coral amendment that imposed fishery closures and gear restrictions on a substantial portion of the monument.

“Which is great! I worked on that,” said Auster. “But it is reversible.”

The New England Fishery Management Council declined to comment on the record for this piece.

Despite pressure from the Councils, Rieser doubts there’s much political incentive for President Trump to open the Pacific monuments; Hawaii is unlikely to vote to reelect him in November, while Maine’s second district is less certain. It’s also unclear whether Trump can legally undo his successors’ protections under the Antiquities Act. The Conservation Law Foundation, Natural Resources Defense Council, and the Center for Biological Diversity have challenged his executive order in court.

Meanwhile, the Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association has filed a petition to the Supreme Court that disputes the use of the Antiquities Act in the ocean.

During his time in office, Trump has made unprecedented overtures to the commercial fishing industry, promising in May to “identify and remove regulatory barriers restricting American fishermen and aquaculture producers.” And he has been testing the vulnerabilities of the nation’s MPAs since he took office. In 2017, at the same time that he ordered the review of the national monuments that culminated in the Northeast Seamounts and Canyons rollback, he threatened to open the marine sanctuaries up to offshore drilling.

This set off a flurry of advocacy for MPAs, but the results of that review, delivered by the Secretary of Commerce later that year, were never made public.

In 2018, Trump replaced the National Ocean Council, established in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, with a new Ocean Policy Committee that stripped language of environmental stewardship and the protection of biodiversity from its goals.

Last September, the MPA federal advisory committee, which was chartered by President Bush in 2003, was terminated along with a slew of other federal committees that the Trump administration has declined to renew.

“It’s cliché at this point, but prior to the Trump Administration, there was kind of a protocol with the way things were done,” said Lindholm. “A lot of those safeguards have really kind of dropped away.”

Banner photo: Reef Shark and fish in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. (Credit: NOAA)