I remember the feelings of newness, possibility, and responsibility as I sat with classmates in Harvard’s Tosteson Medical Education Center in 2012, each of us staring at a blank sheet of paper.

As one of our first medical school assignments, we were tasked with writing a letter to ourselves that we would open – four, five, or in my case, nine years later – right before graduation.

What could I tell an older, more experienced, and more knowledgeable version of myself, who would have the titles of Doctor of Medicine (MD) and Doctor of Philosophy (PhD)?

I mustered up some thoughts, jotted them down, placed and sealed the letter in an envelope, and handed it in. After about a week, I forgot all about my letter.

This essay is part of “Agents of Change” — see the full series

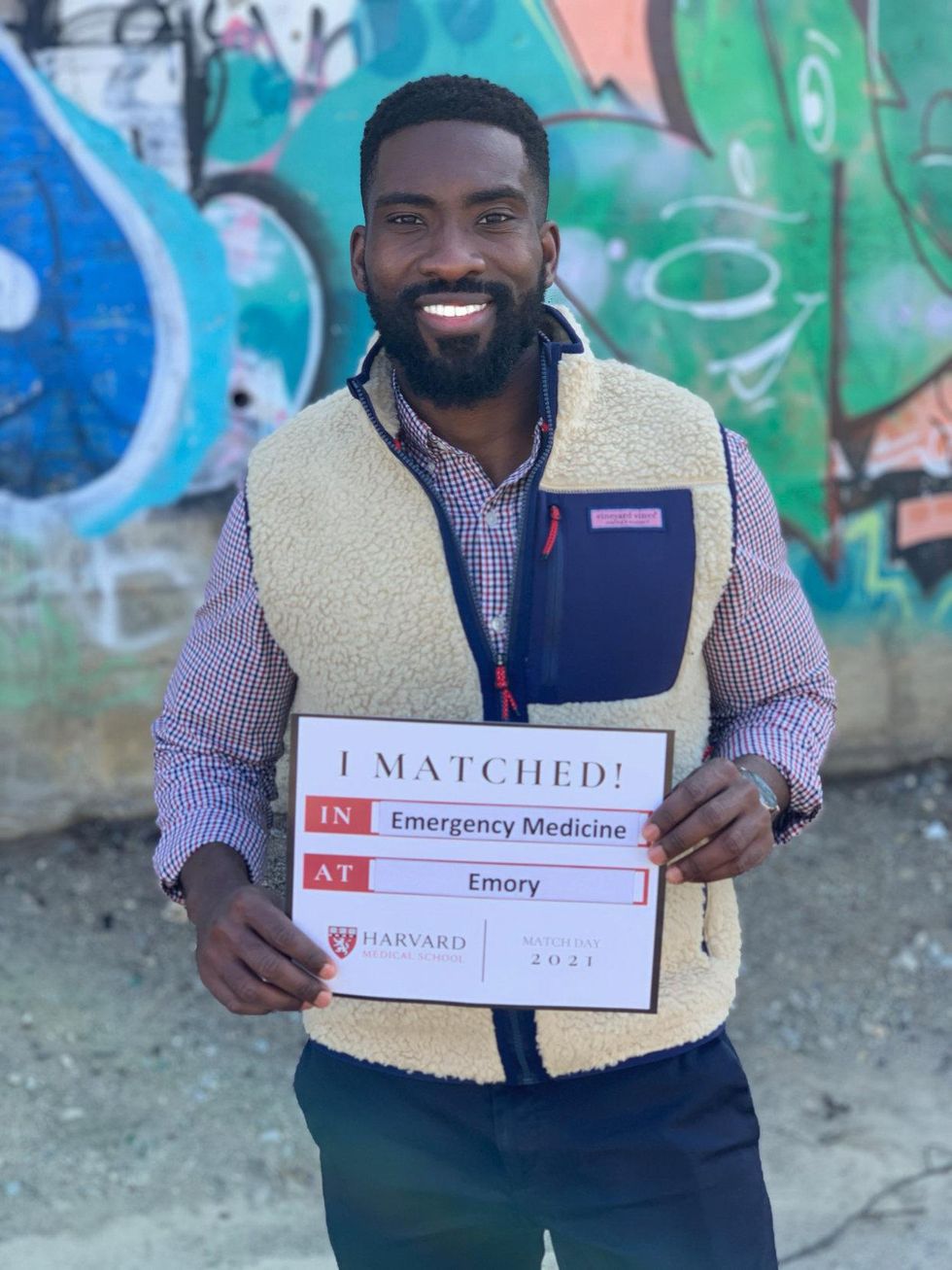

This past March, all graduating medical students received emails telling us we would each receive our letters just in time for Match Day – the day when medical students around the country find out where they have been placed for residency training.

Now, as I sit prepared to open this written time capsule, I think about the journey that has brought me to this point. Since writing that letter, I’ve become even more aware of the privileges that I have received and the responsibility that I am tasked with. People trust me with their lives, and I see many at their most vulnerable. I’ve worked to build skills at the intersection of research, policy, and medicine because I want to treat illnesses while fostering community health and highlighting current systems that leave certain groups to shoulder the burden of environmental exposures and other ills.

Throughout my training, I’ve worked to keep hold of what first inspired my journey and continues to guide and inspire my work – people.

Higher education to serve communities

Match Day and the residency application process was demanding. I found myself in an ongoing state of personal reflection.

I reflected on my own immigration story, moving from Nigeria to North Carolina with my parents as an infant. My parents immigrated to the U.S. in the hopes of obtaining an education to better their family, their community, and the world. From an early age, I too adopted the principle of “higher education for community service.”

Observing ill family, community members, and friends in Nigeria and the U.S. gave me an early appreciation of global health disparities and inspired my pursuit of medicine. I entered Morehouse College, the nation’s only historically Black men’s liberal arts college, intending to pursue medicine. However, through the Hopps Scholars Program and other initiatives, I fell in love with scientific research. I came to appreciate that by informing and advancing public health practices and clinical care, research has a boundless ability to help people. Upon graduation, I enrolled at Harvard to become a physician scientist.

Each of my patients in medical school served as a “professor of life” leaving me with unforgettable lessons about how their health status was often entwined with social factors, including the environments in which they lived. It is difficult to manage a young girl’s asthma or a young man’s depression if you don’t consider the air quality in her neighborhood or the safety of his home. I learned to see people, not just their disease.

In my PhD research I studied the relationships of human health with outdoor air pollution. I emphasized working on biomarkers, molecular indicators that can help us better detect harmful environmental exposures. The sooner we can detect harms, the sooner we can intervene. Potentially before individuals become ill.

This essay is also available in Spanish

In my postdoctoral work at UC Berkeley, I added approaches to my study designs to better appreciate the social systems embedded in environmental exposures. Whether we are discussing metal in water or air pollution, these exposures don’t simply appear and meet people in isolation. They meet people in the places they live, eat, play, and work. For instance, when someone is exposed to harmful lead levels, it’s likely from the water they drink, old paint, or contaminated soil. Thus, studying the harmful effects of lead in these people is incomplete if their water sources, homes, and neighborhoods are also not considered. Understanding this interconnectedness is particularly important when trying to prevent additional harms. Similar to caring for patients beyond their disease, through my science, I work to see the people and communities, not just the data.

I also added a Master’s degree in public policy to develop skills in areas like negotiation, stakeholder analysis, and implementation. As the COVID-19 pandemic has reminded us, science does not operate in a silo. Scientific discoveries, including those in public health, need the attention and buy-in of those working in areas like business and government to fully benefit the public.

This may seem like a lot of schooling, but each step focused on being an effective changemaker in the real world. These investments were made with the hope that when faced with real challenges, practice will have made me better – even if not perfect – and I can confidently answer any call to serve.

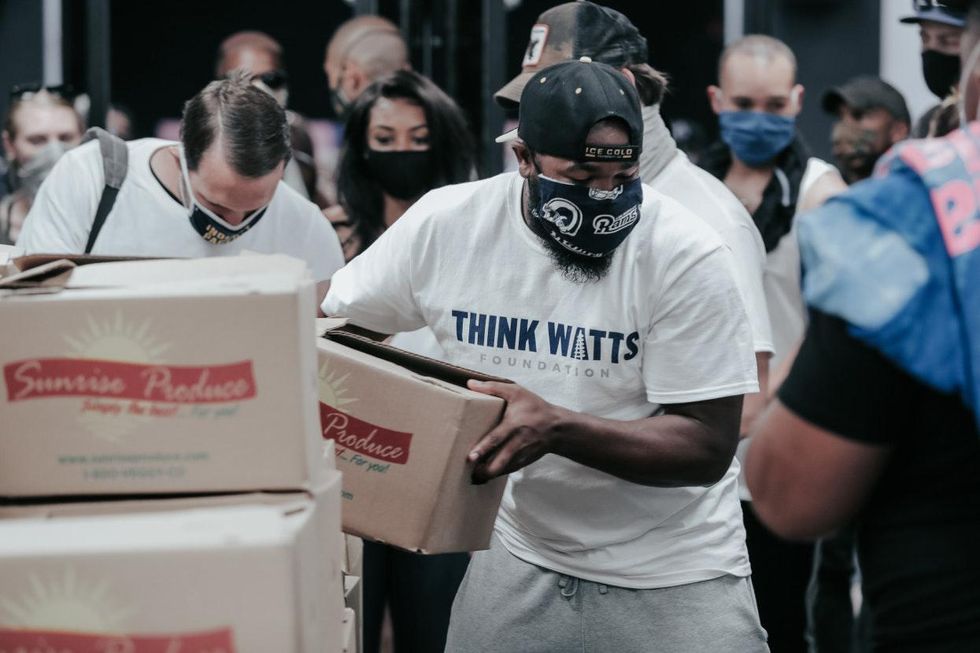

“In support” with communities

Just as the residency interview process was wrapping up, I received invitations to give research talks. I centered one talk on the idea of “being in support with communities.”

I called on listeners to think about a time when they were supported by a community. I also called on listeners to think about a time when they were supporting a community. Then, I called on the listeners to hold both of these ideas at once—this is what is meant by being in support with communities.

My entire personal and professional journey has been about being in support with communities. Relatives, community members, instructors, patients, and so many others sacrificed to make my journey possible. They continue to support me. For instance, if not for the exposure to research, graduate school tours, and other experiences that I received as a Hopps Scholar at Morehouse College, I may not have pursued PhD training. If not for the health disparities I observed in communities in North Carolina and Southeast Nigeria, I may not have pursued medical training. If not for the gaps in the health systems and lack of diversity and inclusivity in research that I have become aware of through my MD/PhD training, I may not have pursued policy training.

This particular presentation also provided me with a real-time opportunity to be supportive of my community. Toward the end of the presentation, I received a question from a Black student that reminded me of the importance of representation in the environmental health space.

Student: “I know for a lot of us who are looking to go into academic careers, sometimes it’s hard finding institutions and spaces who are willing to hear our stories and sometimes you can get caught up doing research that maybe you’re not necessarily interested in or maybe you’re not personally affected by. But you seem to do a really good job of relating your experience to your research. Can you talk a little bit about how you do that?”

In response I said, “When you go back and reflect on things it’s like ‘oh this fits here and here,’ but as you’re walking through those steps it’s not that straightforward … I would say, don’t get frustrated on the front end. The learning of basic research skills and building up your own acumen helps regardless. Once you build yourself up, there is room for you to pivot and directly pursue things that fit your story or your experiences.”

Serving communities through emergency medicine

After years of training, and reflection on how I can use it to best serve people most in need, I’m headed to the emergency room.

When most people think about emergency medicine, they think about ambulances, sirens, and gory trauma. However, the emergency room also serves as a safety net for many vulnerable populations (individuals without primary care providers, the uninsured, patients lost to follow-up). Although it is not ideal for an emergency room to serve this purpose, these patients still show up and need help.

Many of these same individuals experience the brunt of health system failures and health disparities worldwide. They bear a disproportionate burden of toxic exposures and other environmental injustices. They are disenfranchised by racism and other forms of systemic oppression in our society. Again, these people exist beyond their diseases and to be truly effective, their “treatments” must be holistic – potentially requiring medicine, research, and policy solutions.

For this reason, emergency departments are an ideal place to continue learning, advocating, and serving for someone with my skill set.

“You have a duty to help everyone”

On March 19, 2021, I was thrilled and grateful to learn I’d be a resident physician in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Emory.

I also opened my letter from nine years prior. I wondered if I would even recognize myself in it. I did.

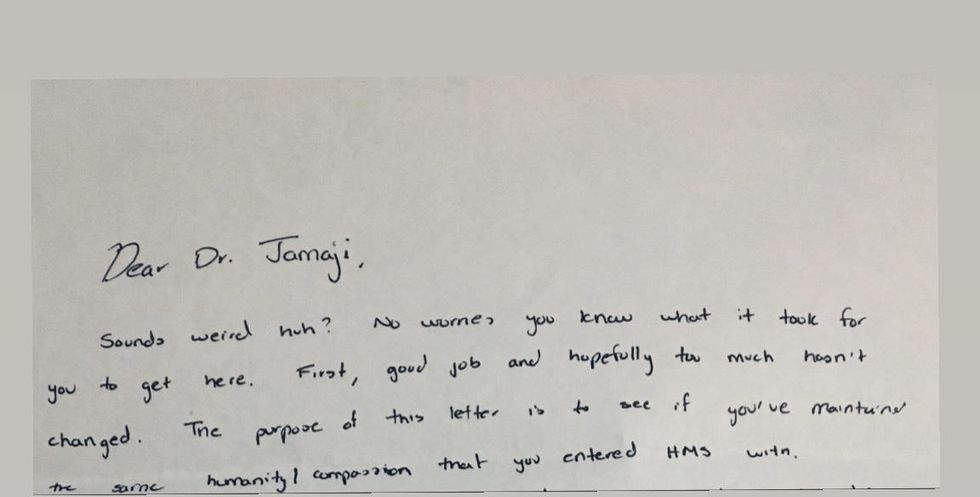

“Dear Dr. Jamaji,

Sounds weird huh? No worries, you know what it took for you to get here. First, good job and hopefully too much hasn’t changed. The purpose of this letter is to see if you’ve maintained the same humanity/compassion that you entered HMS with … it’s not all about you and I want to make sure that you never forget that … by starting your life as a doctor, you have a duty to help everyone. Maintain your strong relationship with God as he has made everything possible. Also, never stop mentoring. Always remember the importance of fostering the future … Very few make it and are given the opportunities that you have so NEVER FORGET …

Live, Love, Laugh,

Jamaji August 30, 2012 1:27 PM TMEC Amphitheater”

As I transition to my new role, I take these words, my experiences, and all that I have learned with me.

There is so much work to be done to make the world more equitable. I remain energized and committed to doing my part and working with communities to help actualize this healthier and more equitable future.

Jamaji Nwanaji-Enwerem is an Emergency Medicine Resident Physician at Emory University School of Medicine and an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Environmental Health at Emory Rollins School of Public Health. You can contact him on twitter @JNwanajiEnwerem

This essay was produced through the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice fellowship. Agents of Change empowers emerging leaders from historically excluded backgrounds in science and academia to reimagine solutions for a just and healthy planet.

Banner photo credit: Matheus Ferrero/Unsplash