PITTSBURGH—A group of local physicians, researchers, community advocates, and elected officials released a declaration today calling for action on cancer-causing pollutants in southwestern Pennsylvania.

The declaration, signed by more than 30 local organizations and 25 individuals so far, explains that rates of several kinds of cancer are “strikingly high” in the region—higher than state and national rates—with disproportionate burdens on people of color and marginalized communities. It calls on leaders across a diverse range of sectors—local businesses and elected officials, foundations and nonprofits, research institutions and health care facilities—to take concrete actions aimed at reducing people’s exposure to cancer-causing chemicals in the region.

“We all know someone who has been affected by cancer, whether it’s an immediate family member or a partner’s cousin or a friend,” Alyssa Lyon, a co-author of the declaration and director of the Black Environmental Collective, an environmental and racial equity advocacy group, told EHN. “This is an issue that permeates everyone’s communities and sits right at the intersection of equity and environmental justice.”

While there are local initiatives aimed at reducing smoking and promoting healthy lifestyles, the declaration’s authors note other factors play a role in cancer rates. A recent study estimated that even if everyone in Allegheny County (which encompasses Pittsburgh) had quit smoking 20 years ago, lung cancer rates would only be 11 percent lower—due in part to the region’s long-standing problems with carcinogenic pollution in air and water.

The group that authored the declaration, the Cancer & Environment Network of Southwestern Pennsylvania, grew out of a national symposium on cancer and the environment hosted in Pittsburgh in 2019.

“I’ve never experienced anything quite like what happened at the end of that symposium,” Dani Wilson, executive director of Our Clubhouse, a Pittsburgh-based cancer patient support organization, told EHN. “After learning what we did, no one there wanted to just walk away.”

Two years and one pandemic later, the group is calling for “bold action on a cancer prevention strategy that is often overlooked: reducing environmental chemicals that are put into our air, water, food, homes, workplaces, and products,” according to the declaration.

“We want this to be transformational—not just a promise toward a better future, but an actual blueprint for a way forward,” Lyon said. “If everyone does their own small part, we can collectively create big changes.”

“Unnecessary” exposures to cancer-causing toxics

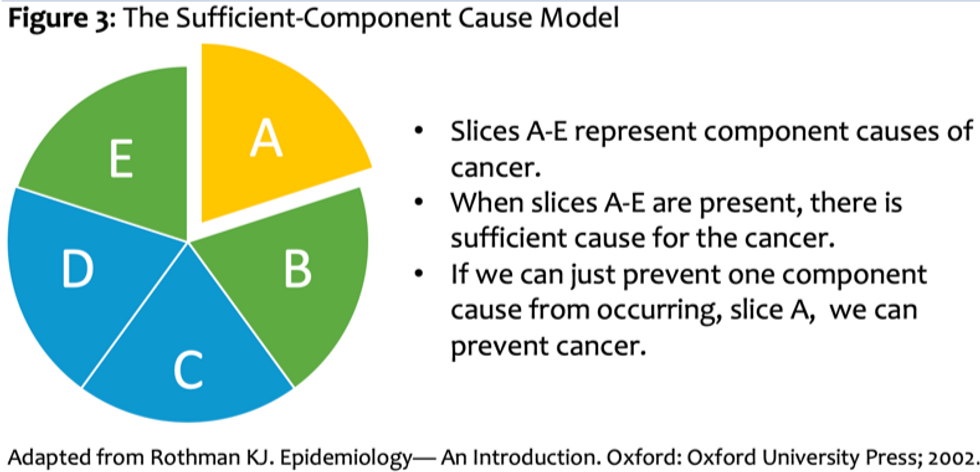

The declaration states that residents of southwestern Pennsylvania are “exposed unnecessarily to environmental carcinogens,” and explains that while exposure to any one pollutant may only pose a small increased risk of cancer for an individual, widespread exposures can result in a significant rise of cancer cases in the region.

Among those exposures they list:

- Air pollution, pointing to research showing that 96 percent of counties nationwide have lower cancer risks from hazardous air pollutants than Allegheny County.

- Emissions from oil and gas wells, which have been shown to increase rates of childhood leukemia

- Carcinogens, such as bromodichloromethane and Hexavalent chromium, in the region’s drinking water

- Radon, which is the second leading cause of lung cancer in the U.S. behind smoking and is ubiquitous in Pennsylvania

- Carcinogens in consumer products like cosmetics, furniture, building materials, and home and garden pest control products

“These issues didn’t just go away during the pandemic,” Olivia Benson, chief operating officer for the Forbes Funds, a foundation that supports southwestern Pennsylvania nonprofits, told EHN. “We know these types of environmental exposures disproportionately affect marginalized people and people of color.”

The Forbes Funds signed onto the declaration, but Benson signed as an individual, too. Her grandmother and an aunt who lived in southwestern Pennsylvania died “too young” as a result of breast cancer and ovarian cancer, respectively. She pointed to research showing that Black women in southwestern Pennsylvania have some of the highest mortality rates in the country.

“I can’t help but wonder, if environmental justice and racial equity were centered here…would they still be here today?”

Following the science on cancer

The declaration references 15 scientific studies, and the group also published a companion document with more in-depth science.

“Everything in the declaration is driven by science,” Polly Hoppin, one of the researchers who helped organize the 2019 symposium on cancer and the environment that spurred the creation of the Cancer and Environment Network of Southwestern Pennsylvania, told EHN. Hoppin is a former Senior Advisor at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Environmental Protection Agency and the program director at the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production at the University of Massachusetts. She also serves as a facilitator for the Network.

In the science document, the authors used data from the National Cancer Institute’s cancer registry to describe national trends in cancer rates and show how locally cancer rates generally mirror national trends, but several cancer types associated with environmental exposures are higher than state and national rates.

These include elevations in lung cancer, leukemias, and thyroid cancer across multiple counties in the region (although not always in both males and females), and elevated rates of childhood cancers in Greene County, Washington County, and Westmoreland counties.

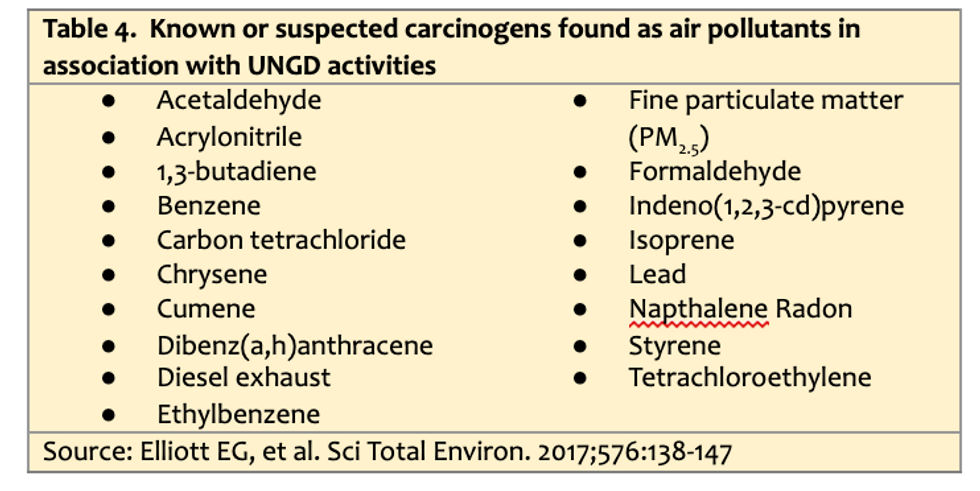

The document points to research showing that among the more than 200 air pollutants detected in emissions from oil and gas wells, nearly two dozen are considered known or suspected carcinogens (an investigation into the cause of numerous cases of rare childhood cancers in the region is ongoing).

The science companion document also delves into the most recent science on the ways exposure to air pollution, water pollution, pesticides, and carcinogens in consumer products can cause cancer to develop, then reviews the specific exposures happening in southwestern Pennsylvania.

For example, it references data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s National Air Toxics Assessment showing that Allegheny is in the worst 4 percent of counties in the nation for cancer risk from all forms of toxic air pollution (including traffic and industrial emissions), and in the worst 1 percent of counties nationwide for cancer risk specifically from air pollution caused by industrial manufacturing—and notes that nearly 90 percent of those emissions come from U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works facility.

In a discussion about the region’s drinking water, the science companion document points to research showing that public drinking utilities in Pittsburgh and its suburbs frequently report potentially dangerous levels of suspected carcinogens like bromodichloromethane, hexavalent chromium and chloroform. In rural parts of the state, there have been more than 300 confirmed cases of private drinking water wells being contaminated by the oil and gas industry.

Because these issues are so widespread and come from such diverse sources, Benson said, no single group can tackle the problem on their own.

“This is a problem that requires system-level change to address,” she said.

Finding solutions to the pollution

The declaration lays out a series of priorities for diverse groups, including:

- Speak up about exposures to carcinogens, and mobilize community institutions—including childcare centers, schools, businesses and places of worship—to take their own steps to reduce pollution and create healthy environment (for community leaders)

- Protect workers and fence-line communities from exposure to toxic chemicals used and released in manufacturing by implementing state-of-the-art operations that reduce pollution and preserve resources (for businesses)

- Enforce laws and regulations and issue substantial and escalating fines to companies that repeatedly violate regulations and pollute the food we eat, the air we breathe and the water we drink (for public officials)

- Advocate for health care institutions—for example via procurement policies—to purchase safer products and specify healthy building materials for construction and renovation (for health care professionals)

- Hold government decision makers accountable for implementing and enforcing policies that protect public health and increase reliance on safer alternatives over time (for environmental and public health advocates)

- Encourage collaboration across sectors and systems approaches to catalyze change at the scale needed (for philanthropic organizations)

- Prioritize research and development to meet necessary societal needs with materials, technologies and chemistries that do not contribute to cancers and other health problems (for research institutions)

The authors believe southwestern Pennsylvania is uniquely positioned to make meaningful changes to reduce local cancer rates because of the region’s high volume of research institutions, healthcare facilities, and effective nonprofit organizations.

Lyon noted that Pittsburgh is among the top metropolitan areas in the U.S. for both number of charitable foundations and per capita investment by foundations.

“Pittsburgh is so small that means we all have one degree of separation from the top person at a foundation,” she said. “That means we can afford to put all the right minds in a room together and figure out what equity for everyone in the city really looks like.”

Banner photo: 2019 cancer and environment symposium. (Credit: Kristina Marusic for EHN)