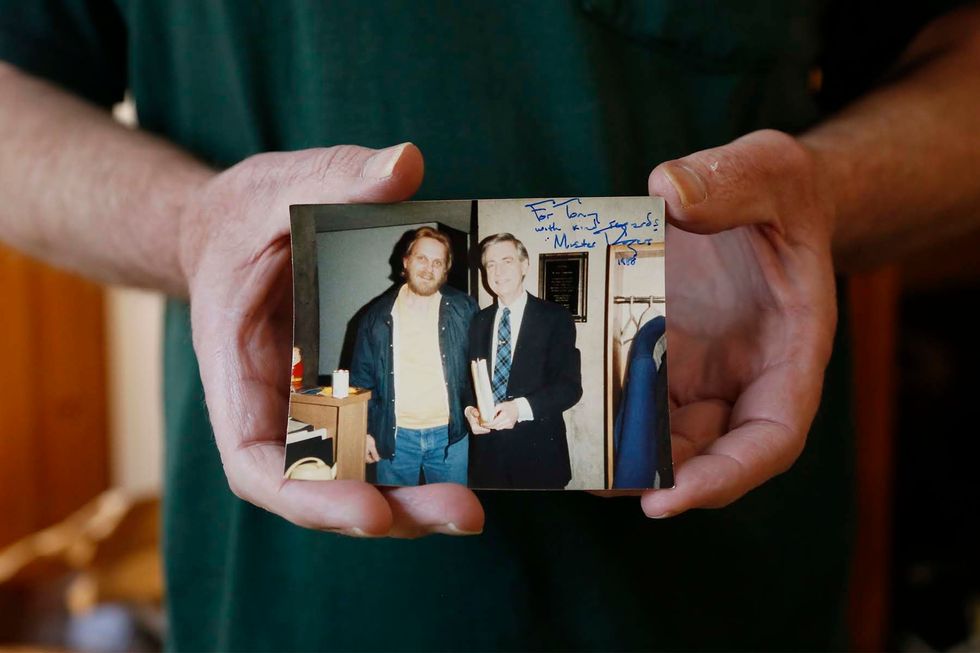

Anthony Wolkiewicz had his picture taken with Fred Rogers while working at WQED in 1977.

Rogers made a special point to ask about Wolkiewicz’s youngest son. “Who is this? I don’t remember him in my neighborhood,” Wolkiewicz remembers him saying in the same voice he used on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

It’s sheer luck that Wolkiewicz still has that photo: he lost many of his cherished photographs when his basement flooded in June 2017. More than 2 inches of rain fell in an hour, he said, and Saw Mill Run Creek behind his house “became a raging rapids.”

“It crested over its banks, and I got 4 feet of water in my basement,” Wolkiewicz, 65, recalled.

He watched as a television was carried along the stream behind his house. The street in front of his house flooded, too, so water was pouring in from both directions.

“It’s like if a dam was up the road and someone opened the floodgates. Up it came and over the bank, and done deal,” he said. Insurance money covered his major appliances but not many of his other smaller items, including his electronics, which filled a dumpster. He estimates he lost $20,000 worth of items. The flood water was mixed with sewage, so his five nephews helped to spray the entire basement down with bleach water. He was without air conditioning for two weeks, which exacerbated a breathing condition.

Wolkiewicz bought his home along Provost Road in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Overbrook in 2011 for about $34,000. He said his neighbors told him then that flooding wasn’t a big problem. But in June 2018, his house flooded again.

Now when it rains, he stays home to pile sand bags and make sure debris from the flooding in his basement doesn’t block up the sewage drain.

None

More rain has fallen in the Pittsburgh area over the last two years than at any other time in recorded history. Two of these storms have resulted in deaths in the past decade, as drivers were caught on roadways that flooded.

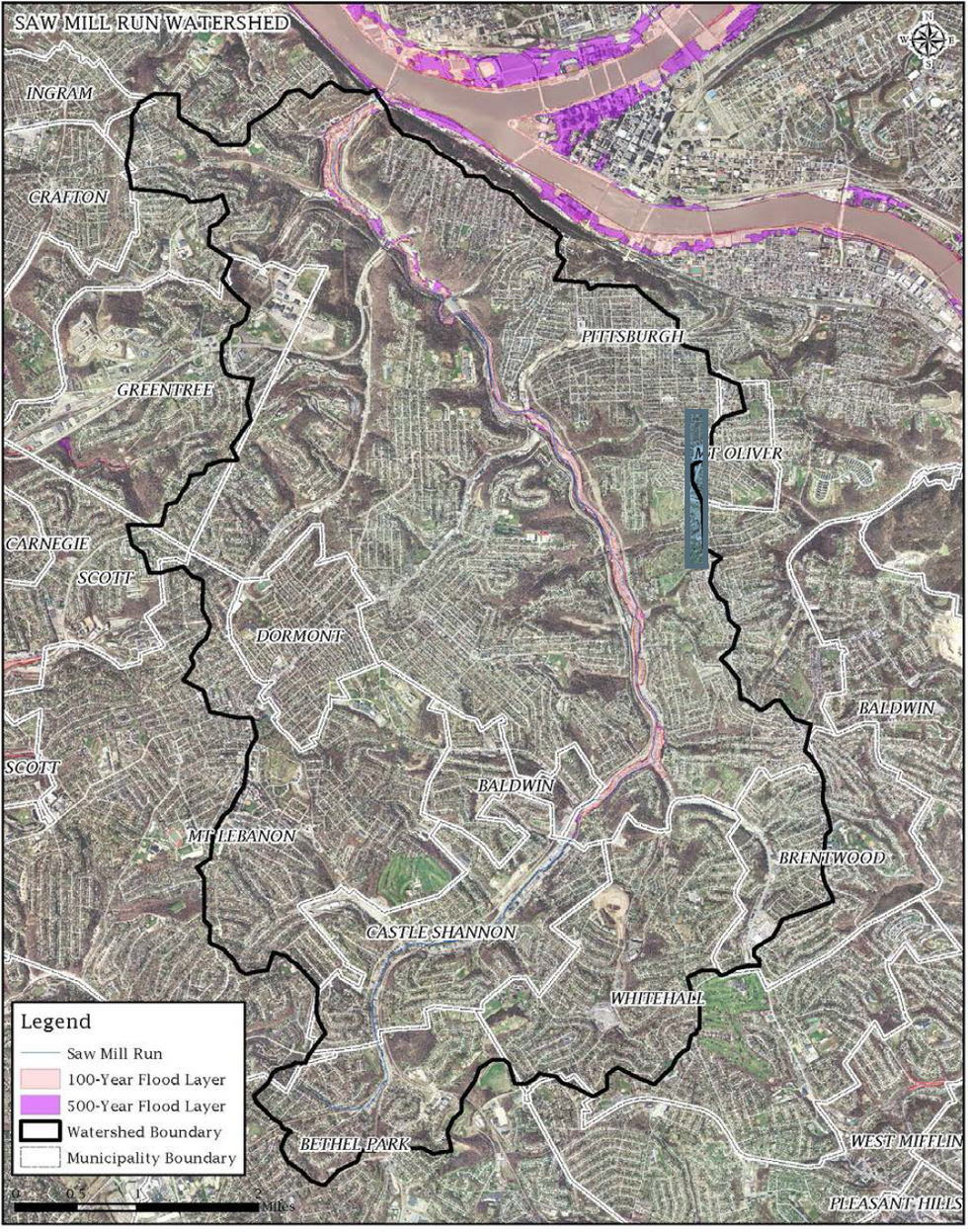

The area where Wolkiewicz lives along Saw Mill Run in the South Hills is one of the worst in the Pittsburgh region for flood risk. But it’s not the only area. Flooding has become pervasive, with massive damage to the suburbs of Bethel Park and Upper St. Clair and whole sections of towns like Etna and Millvale.

Stories like Wolkiewicz’s have become common across the region.

Wolkiewicz could build a wall in his backyard, he said, but that would just push the flooding down into his neighbor’s yard. That’s the same problem facing local boroughs and agencies like the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority [PWSA]. If you stop flooding in one location, how do you create a permanent fix that doesn’t just make rushing water your neighbor’s problem?

And in Saw Mill Run, it’s particularly complicated: the houses across the street from Wolkiewicz are located in the borough of Whitehall, with a totally different local government. Saw Mill Run has become one of the region’s most important test cases for what the whole region may need to consider: working proactively across political boundaries to address the flooding.

Experts and local community leaders have been developing plans but still don’t have the support to implement them at the scale that is needed. Possible solutions include buying up perpetually flooded houses and businesses, turning sections of the watershed back into natural floodplains instead of concrete lots, and developing flood control projects that cross municipal boundaries. But doing so is easier said than done in a county that’s one of the most fragmented in the country.

Otherwise, residents like Wolkiewicz and his neighbors are left dreading rain that could mean a loss of property, or worse. Last summer, he paid $1,000 to turn his garage door into a brick wall in the hopes it will keep the water out. He won’t know if it will work until the next flood comes.

Overbrook

In July, about 40 concerned citizens from Overbrook showed up for a community meeting to hear what local leaders plan to do about Saw Mill Run.

Residents often interrupted presentations from PWSA to talk about flooding problems on their own streets.

Kate Mechler, the deputy director of engineering for PWSA, said the agency would try to respond to each of the specific complaints. “We have started a stormwater investigation team,” she said. “This team is hammered. We get a lot of calls.”

PWSA couldn’t quickly fix each of their complaints, Mechler said, without looking at how those fixes would affect their neighbors and others in the watershed. “We don’t want to keep pushing water where it can’t go,” she said.

Anthony Coghill, the Pittsburgh city councilman for most of the Saw Mill Run area, sees the problem as nearly beyond repair. As a roofer, he said he understands how water moves across roofs, down gutters and into the streets and sewers. He thinks there is only one answer.

“I’m tired of saying, ‘We’ll get an engineer out here,’” Coghill said. “The bottom line for me, when I see the devastation going on … Buy out.”

The Saw Mill Run watershed includes more than 14 Pittsburgh neighborhoods and a dozen municipalities. Coghill proposed that the city allocate $2.1 million to buy out the homes of city residents with the most flood-prone properties on Provost Road. Although Coghill pushed for the idea with the city, its 2020 budget did not include this funding.

Steve Kaduck, who runs an auto upholstery business in the neighborhood, agreed with Coghill that the best solution was to buy out the Provost Road homes and turn it into a basin to catch floodwater. “Until they find a retaining space or a new pipe going to the river, it ain’t going to stop,” he said.

But he’s seen flooding there for 50 years and nothing has been done. He said he feels frustrated that their problems have recently taken a backseat to flooding in suburban communities, like Bethel Park and Mt. Lebanon. “We don’t make the news anymore,” he said. “We’re not news. We’re old news.”

Saw Mill Run

Back in October 2018, Lisa Werder Brown, the executive director of the Watersheds of South Pittsburgh, drove along Saw Mill Run Boulevard and started counting used car lots, which she perceives as a sign that new businesses are wary of flooding risks.

To really turn Saw Mill Run around, she said, the region needs to turn large chunks of the valley next to the creek back into a natural floodplain. She said it should become natural parkland that would become an amenity people would want to visit rather than avoid.

But doing so would require a large investment to buy properties already there. According to Brown, the federal government finds more value in buying out property in wealthier neighborhoods, like the agency recently did in Upper St. Clair, an affluent suburb outside of Pittsburgh, she said.

In October, Ana Flores, the Ohio River sewer shed coordinator for PWSA, visited a small stretch of Saw Mill Run Creek. So much water pours into the stream during storms, moving at such a high speed, she said, that it’s ripping soil from the bank and pulling it into the stream. That’s exposing tree roots and causing whole trees to fall in.

She pointed to a tree log that was jammed up against a small bridge. The water in a previous storm was strong enough to carry the trunk downstream, she said. So much soil is eroding that eventually the roadway next to the stream may start to cave in.

PWSA’s plan for this 200 feet of creek is to change the angle of the bank to rise gradually, like a skateboard ramp, rather than like the vertical wall it is now. That will slow the water down and prevent erosion. It’s a small project for a creek that has problems all along its 9-mile length.

Flores hopes to return to build a more ambitious stormwater project. On the other side of the bank, 5 acres of gravel and brush have sat empty for more than two decades. The federal government purchased 20 properties there that flooded repeatedly in the mid-1990s, with the stipulation that the land could only be used for natural purposes.

None

The City of Pittsburgh now owns the property, known as Ansonia Place. If turned into a natural floodplain, the abandoned neighborhood could function like a giant bowl in heavy rain, soaking up and slowing down rainwater before it floods the streets and homes downstream.

Brown said PWSA’s projects so far have been relatively small and even the smaller communities in Saw Mill Run have realized they need to build bigger projects closer to the stream. “Folks have realized that they could dump exorbitant amounts of money into projects within their own communities and still not make a dent,” she said.

PWSA has been meeting with 11 other municipalities upstream of Pittsburgh since 2015, trying to create a single vision for the watershed. The “integrated watershed” group is looking to get regulatory approval for a pollution credit system, so each municipality could get credit for cleaning up the creek with regulators, even if a project is sited outside its own boundaries.

One hope, Flores said, is that the integrated watershed plan they are developing will allow them to start building stormwater projects upstream. “We’re waiting to see how much work we can do up at the top, so we can slowly make our way down and do it in an order that makes sense for the watershed,” she said.

PWSA is also negotiating with the City of Pittsburgh to determine who will be responsible for which aspects of flood control. Right now, PWSA only has authority from the state to take on projects that improve the water quality above ground or stop flooding in basements and its underground pipes.

Beth Dutton, the senior group manager for stormwater at PWSA, said the current lack of clarity about which agency is in charge of flooding in the region means there isn’t a coordinated response.

“It’s kind of the Wild Wild West for flood management,” she said.

Individual actions

Several community watershed groups have formed in the recent past to tackle flooding challenges, but not all communities have one.

Back in 2005, after heavy flooding from Hurricane Ivan, residents formed a watershed association for Big Sewickley Creek, about 20 miles northwest of Pittsburgh. The group fizzled quickly.

Last summer, about 25 community members showed up to talk again about the future of Big Sewickley Creek after two years of dramatic rainfall. Gary Sherman and Frank Akers, two residents who attended, are not typical environmentalists who live on the creek: they are hunters who hope to get royalties from fracking on their land.

They’re worried that new housing developments upstream are causing more water and construction material to end up in the stream. The flooding problem keeps getting worse, they said, and they want to protect the land near their homes.

In 2018, Donna Pearson and Melissa Mason decided that they needed to do something to protect their community after heavy rains during a July storm flooded Millvale, a town next to Pittsburgh and Etna. They formed Girty’s Run Watershed Association.

Pearson said she spent whole days working on the watershed association in its initial days and would be interested in working on the issue more if she could get funding. For now, she is focused on educating residents. “We are never going to fix the flooding,” she said. So instead she hopes to “improve the response to it, and improve the health of the stream and the communities around it.”

Although these actions, on their own, may not lead to great change, a report released last year by the Water Center at the University of Pennsylvania and The Heinz Endowments* suggests these individuals may be paving the only path forward for the region. The report recommended investing in an incubator and an activist network.

“Within these local laboratories are the next generation of water leaders who, in the absence of political will among large institutions, must be nurtured and equipped to lead in 10, 20 or 30 years when generational changes are likely to change the political calculus,” the report said.

Some changes are being made regionally. In 2020, the Allegheny County Sanitary Authority [ALCOSAN] is taking over responsibility for the region’s largest sewage lines from local governments after years of recommendations and negotiations. It’s the beginning of a more centralized sewage system. Increasing pressure from government regulators to clean up polluted water is also spurring between $2 billion to $6 billion in investments over the next two decades by local municipalities and agencies like ALCOSAN and PWSA.

Etna Borough Manager Mary Ellen Ramage said she believes local leaders will have to give up some control. Etna’s borough offices flooded up to its light switches in 2004. Since, Ramage has learned that stemming the flooding in Etna depends on fixes made by municipalities miles upstream. Etna is at the end of a sieve, she said: with less than 1% of the land in her watershed, most of the floodwater originates upstream.

While experts have recommended changes to Allegheny County’s fragmentation for decades, there is precedent for regionalization. In 2018, the Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority in northeastern Pennsylvania brought together 32 small communities to collectively manage their stormwater responsibilities. The agency’s leaders noted that they’re collectively saving as much as 50% of their costs by working together.

The new authority can build stormwater projects “anywhere in the watershed,” Adrienne Vicari, a consultant for the authority, said at an October 2018 sewage conference in Monroeville. That freedom allows the authority to tackle the region’s biggest water problems at the lowest price.

But local leaders aren’t so optimistic.

Researchers of the 2019 Water Center/Heinz report interviewed more than 40 of the region’s key water stakeholders and found little to no interest in moving forward with a regional stormwater agency.

Instead, the report said, the region must foster a bottom-up approach that will pave the way. The fragmentation of local government is often thought of “as a source of political inertia and a hindrance to action,” the report said. “However, opportunity comes not from obliterating these boundaries … but in leveraging local energies.”

Data ahead

Thomas Batroney attends a lot of public meetings in the Pittsburgh region for his job as a senior project engineer for a global engineering, management and economic development firm. He started noticing that “everyone is talking about the same problem.” In August 2019, he began cataloguing all of Allegheny County’s major flooding events in a blog he calls The Pittsburgh Urban Flooding Journal.

He created detailed illustrations of rainfall patterns and inserted links to news stories and videos. He’s in the process of adding a map layer that shows what streets flooding has been reported on.

While each of the individual storms can seem like isolated incidents, Batroney’s blog organizes them into a larger narrative of a region battered by persistent, unrelenting flooding. “Localized flash flooding in the Pittsburgh region is a serious epidemic and chronic illness,” he wrote in his first blog entry.

Batroney said he thinks the region needs a flood control or stormwater district, like the ones found in Houston, Phoenix, Denver or Chicago.

After a giant flood in Pittsburgh in 1936, Batroney said, the region came together to solve the flooding problems from its three major rivers. The flood killed 62 people, injured 500 and left more than 135,000 homeless in the region. The Flood Commission of Pittsburgh, which originally only covered the city, expanded to include more than 400 groups across the region. Together, they built support for the construction of 13 large-scale flood protection projects upstream of Pittsburgh.

Batroney said it’s time for the region to come together again before another tragedy.

“It’s not going to get any better … unless we do something, especially with the way the climate projections are looking,” he said. “This isn’t going to fix itself. It’s only going to get worse.”

None

*The Heinz Endowments also provides funding to PublicSource.

Oliver Morrison is PublicSource’s environment and health reporter. He can be reached at oliver@publicsource.org or on Twitter @ORMorrison.

This story was fact-checked by Sierra Smith.

Good River: Stories of the Ohio is a series about the environment, economy and culture of the Ohio River watershed, produced by seven nonprofit newsrooms. To see more, please visit ohiowatershed.org.