Food banks in the U.S. are on course for a preventable collision between record-setting food insecurity and lead-contaminated meat.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic and related economic hardships, 1 in 7 adults with children reported their households lacked sufficient food last month. Reliance on food banks has surged. Each year, hunters donate over 2 million pounds of hunted meat to food banks across the U.S., providing critical nutrition for families in need. However, most states do not implement a lead-inspection program for the meat, even though most of it has been shot with lead bullets.

The implications for lead exposure are significant. According to annual lead inspection results that EHN obtained from Minnesota, other state agencies are likely exempting hundreds of thousands of lead-contaminated meals from inspection each year. Recipients include people who may be most at risk to experience health effects from lead, including children and pregnant women.

Earlier this year EHN reported on the absence of information for hunters about the health effects of lead, and the lack of recognition that eating lead-shot meat is a risk factor for lead exposure. Now, interviews with multiple state agencies have revealed a similar lack of recognition that lead-shot meat is at risk for lead contamination. Experts say that exempting lead-shot meat from lead inspection is a matter of science denial and environmental injustice.

Uninspected meat

Each winter, after the last shot of Minnesota’s hunting season has been fired, a refrigerated truck distributes hunter-harvested deer meat to food pantries. The driver stops at meat processors throughout the state, picking up packages of frozen venison. Within a week, the truckload is delivered to an X-ray facility, where an assembly line of staff from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture (MDA) takes over.

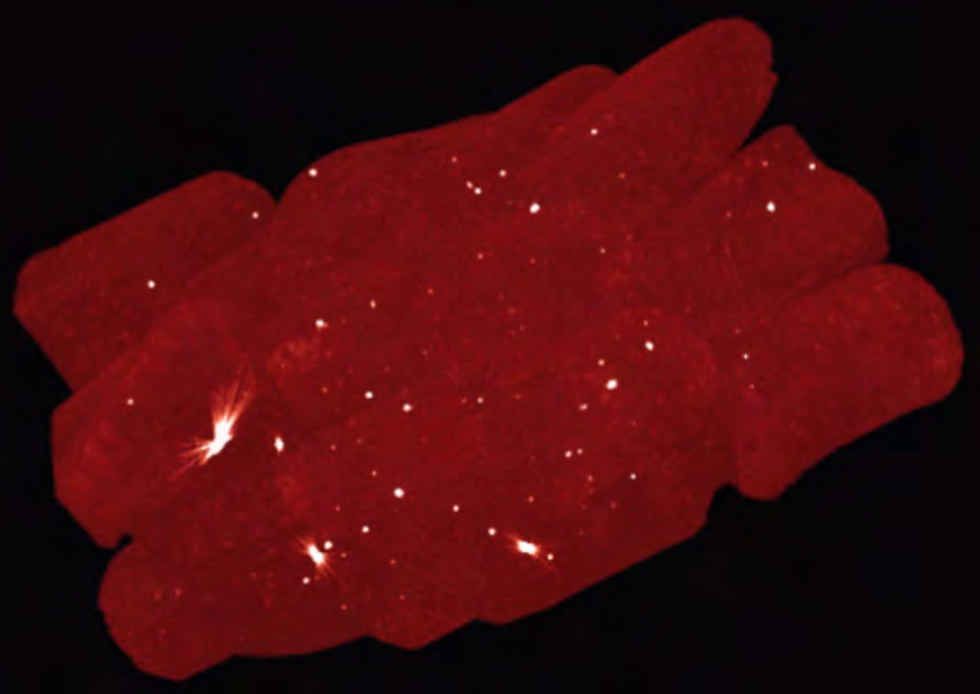

The team unboxes the meat, placing packages on a conveyor belt of an X-ray machine. Inspectors watch for the unmistakable glowing specks of lead, left behind from lead bullets. Contaminated packages are discarded. Meat that passes inspection is loaded back on the refrigerated truck and redistributed to food banks in the region where it was harvested. The X-ray process for more than 10,000 pounds of meat takes approximately 3-5 hours.

The system works—people in need receive several tons of meat that has been screened for lead contamination.

According to the state’s inspection results obtained by EHN, during the past 6 years, an average of 9 percent of packages were contaminated with lead and discarded. Last year alone, 946 pounds of lead-contaminated meat were prevented from reaching vulnerable people in Minnesota.

Related: Lead in hunted meat—who’s telling hunters and their families?

The MDA provides meat processors with inspection results from their donated venison, along with suggestions of how to reduce lead contamination. Experts from the MDA have testified that before the inspection program was implemented, tests found lead in nearly 25 percent of donated venison samples.

The volume of venison donated in Minnesota is an order of magnitude lower than many other states, where lead inspection programs are nonexistent. According to the National Rifle Association’s (NRA) Hunters for the Hungry initiative, the top 5 states for venison donations are Missouri, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Iowa, and Ohio. The states combined for nearly 1 million pounds of venison donated in 2019—all of it uninspected for lead contamination.

The majority of deer hunters use lead ammunition, and several variables influence the extent of lead contamination in hunted meat. These include choice of firearms, choice of bullet type, whether a bullet strikes the animal’s bones, and whether the resulting meat is ground. Without X-ray inspection or chemical analysis, the extent of lead contamination in donated meat is unknown and can vary from year to year. In addition to Minnesota’s ongoing inspection program, past efforts to X-ray samples of donated meat in North Dakota, Iowa, and Wisconsin have also found lead contamination.

“I’m really concerned about the amount of venison that’s being donated unchecked, understanding that most of the ammunition that is used contains lead. I think it’s a serious issue,” Na’Taki Osborne Jelks, assistant professor at the Spelman College in Environmental and Health Sciences, told EHN.”There should not be meat that is accepted and then distributed to families in need if it has not been screened. Especially given the fact that we know there’s perhaps a high probability that some of this meat can be contaminated with lead, which we know to be a neurotoxicant. I’m just kind of blown away by this.”

There is no safe level of lead in the blood. In 2008, a study in Wisconsin calculated whether the average level of lead detected in donated meat would influence the blood lead levels of children who consume it. They estimated that blood lead levels would rise above 10 micrograms per deciliter (ug/dL) in 80 percent of children who ate two meals of the contaminated meat per month. That level of lead in the blood is associated with a loss of 7 IQ points in children. Even levels below 5 ug/dL put children at risk for decreased cognitive performance and behavioral problems.

For pregnant women, a blood lead level of 10 ug/dL has been estimated to nearly quadruple the odds of miscarriage, and to increase the likelihood of preeclampsia, a life-threatening high blood pressure condition, by 16 percent.

Osborne Jelks pointed out that the lack of inspection for lead undermines hunters’ contributions. “I’ve heard of the Hunters for the Hungry program and I know that lots of folks are really proud of those programs. They should be proud for the contributions that folks are making to help alleviate hunger in our country. But we’ve got to be able to look at whether or not the food that is being supplied to families is safe.”

In 2008, former Minnesota Department of Agriculture assistant commissioner Joe Martin released a statement making a similar case for inspection: “Minnesota sets the bar high when it comes to food safety. The donated venison program must meet the same standards we set for regulated food businesses.”

Since then, the inspection program has been paid for with the same funds that support the donation program itself.

“This is a program that is sponsored and funded by the DNR [Department of Natural Resources] here in Minnesota,” Jennifer Stephes, the agency’s meat inspection supervisor told EHN. “We administer the program, and our staff works on the logistics – the trucking, the distribution, the X-ray. MDA incurs those costs, and then we are reimbursed for that through the DNR.”

The cost to inspect roughly 13,000 pounds of donated venison in 2019 was just over $100,000.

Minnesota’s venison donation program is also unique in discouraging grinding meat during firearms season, because the vast majority of lead contamination has been found in ground venison. Typically, ground meat is the main kind of venison distributed by donation programs.

According to Stephes, “Lead is much more likely to be in ground product because grinding it can spread it into multiple packages. Lead is very soft as a metal, so even if there’s one piece of lead, the steel grinding equipment can actually fragment the lead and spread it throughout the venison in the grinding process.” As a result, processors in Minnesota are instead encouraged to donate cuts including small roasts and loin chops.

In states where agencies have not developed an inspection program, a lack of regulation of venison at the federal level has resulted in a lack of inspection at the state level.

The Ohio Department of Agriculture provided EHN with a statement indicating that since venison is not regulated on a federal level, “…it is exempt from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Safety and Inspection and the Ohio Department of Agriculture Division of Meat Inspection inspection.”

In Pennsylvania, the Department of Agriculture referred EHN to the USDA, who pointed out that venison is exempt from their inspections. The agency said the issue is instead in the jurisdiction of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), who replied, “The FDA is available to our state partners for consultation, but we are not directly involved in establishing state policies for the donation of game meats to food banks.”

The Virginia Department of Health provided EHN with a Memorandum from 1992 that states, “Venison which has been donated by the Hunters for the Hungry program is exempt from state and federal meat inspection.”

While agencies in Missouri and Iowa have not provided EHN with an explanation of why lead-shot meat in their states is not inspected for lead, meat processors in both states confirmed that the donated meat they process is not required to be X-rayed for lead contamination. In the past, the Iowa Department of Public Health justified accepting uninspected lead-shot meat by pointing out that concerning cases of blood-lead levels in the state’s children had no history of being attributed to lead in venison. However, it was revealed that the department had no history of asking families whether they ate hunted meat. Other factors add uncertainty to extrapolations from blood test results. Most children tested in Iowa’s program are 0-3 years old, and blood-lead levels tested months after eating hunted meat can be deceptively low since the half-life of lead in the blood is about 30 days.

In response to questions about accepting lead-shot meat that is not inspected for lead, the Central PA Food Bank responded, “We trust the high standards set by the PA Department of Agriculture and the USDA and will take our cues from them on lead contamination in donated meat.”

Food banks in Missouri, Virginia, Iowa, and Ohio did not respond to EHN’s request for comment.

Science denial and the NRA

“Nobody can say that it’s ok to distribute meat contaminated with lead – I don’t think any official authority can say that. Not even in the U.S. It’s a problem.” Jon Arnemo, a wildlife veterinarian, professor at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, and a leading expert on lead-hunted meat around the world, told EHN.

“If you know that someone injected poison into a tomato, you don’t want to eat that. Most likely nobody would want to eat that. But that’s what’s happening when you go hunting with lead,” Dr. Arnemo said, adding that the lack of a policy for inspecting lead-shot meat for lead contamination is consistent with science denial pushed by organizations such as the National Rifle Association (NRA).

In 2017, the NRA encouraged members to oppose a proposed amendment to a House Bill under consideration by the Oregon Senate Committee on Environment and Natural Resources. The amendment proposed to deem donated game meat “unfit for human consumption” if it contained visible lead ammunition. The NRA claimed the amendment was “anti-hunting”, “an attempt to demonize the use of traditional lead ammunition”, and said that “the myths surrounding the use of traditional lead ammunition are based on faulty science made by anti-hunting advocates.”

“If you oppose lead ammunition, you are immediately regarded as anti-gun and anti-hunting. I am a hunter. I have been hunting all my life, for more than 45 years. So I’m not anti-gun. I’m not anti-hunting. I’m simply anti-lead because it’s poisonous,” Dr. Arnemo said.

The NRA’s website, HuntForTruth, claims to debunk the ‘myths’ about lead in hunted meat. According to Dr. Arnemo, “The statements are unbelievable and parallel arguments used by The Flat Earth Society. There is an overwhelming scientific consensus—a huge majority of the scientific community that agree on the facts here. For lead ammunition, it’s a 99 percent consensus – 99 out of 100 papers agree that the use of lead ammunition poses a risk to both humans and wildlife and the environment.To say there’s no proof or no problem just denies 1,000 papers published over the past 30-40 years.”

The NRA did not respond to requests for comment.

Dr. Arnemo said there are numerous peer-reviewed experiments on animals, epidemiological papers on humans, and case reports in human medicine showing that ingestion of lead from ammunition causes increased blood levels. And when it comes to lead, the impacts of exposure cannot be undone. “All the damage you see that lead causes to the nervous system, kidneys, to the cardiovascular system, is permanent. It’s not reversible. So even if at some point in time if you completely stop lead exposure, the damage is there forever. You can’t reverse it.”

Environmental injustice

Food insecurity has soared during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Black, Latino, and Native American people are more severely impacted than White people. Osborne Jelks emphasized this racial disparity, and said that when people who cannot afford to feed their families are forced to sacrifice food safety, it is a matter of environmental justice.

“Given what we’ve seen in other situations where meat has been contaminated, it’s an issue of justice with respect to there not being policies in place—with agencies not taking the responsibility for ensuring that this food supply is safe. I think about the families that are perhaps most in need of resources from food banks, I think about communities that are already impacted by a number of different stressors, whether they be environmental stressors in their community or these kind of social stressors inclusive of income, that complicate things and make these communities more vulnerable to environmental health risks.”

Stephes said this has been part of the reasoning behind MDA’s inspection program, “This venison provides a healthy protein source for an underserved part of the public that tends to struggle in many ways … some may even have a greater risk of lead-associated problems. We do not know the effects of lead until years after the exposure—some of the health effects can be discovered down the road and may be significant. That’s what’s challenging and unique about lead. It’s especially risky with children and pregnant women, as well as adults who have kidney and heart-related risks to their health.”

Osborne Jelks sees a need for swift action to ensure that lead-hunted meat is screened for lead contamination. Dr. Arnemo pointed out that there is another option to keep lead out of food banks. “There is a very easy solution to this if the hunters switch to lead-free bullets, he said. “It’s very easy. Lead-free are as good as the lead-based bullets. The killing efficiency is similar, the bullets behave in the same way, they kill the animals in the same amount of time.”

As for food banks that plan to provide uninspected, lead-shot meat in the coming months, Osborne Jelks said, “I think it sends a message that certain parts of our population are expendable. That there isn’t enough concern about making sure those families are safe, about making sure that the food being distributed is safe.”

Meanwhile, this winter in Minnesota, Stephes will be overseeing the process of discarding lead-contaminated meat. “We are focused on public health; it is supported by multiple health agencies. That’s our job.”

Banner photo: Venison donation by the National Park Service to the DC Central Kitchen. (Credit: DC Central Kitchen/flickr)