Eating an organic diet rapidly and significantly reduces exposure to glyphosate—the world’s most widely-used weed killer, which has been linked to cancer, hormone disruption and other harmful impacts, according to a new study.

Authored by researchers at the Health Research Institute and the nonprofit organizations Commonweal Institute and Friends of the Earth, the study measured glyphosate and its main breakdown product, aminomethyl phosphonic acid (AMPA) in the urine of 16 people (seven adults and nine children) from four demographically and geographically diverse families. Researchers tested participants’ urine for glyphosate and AMPA over six days on a conventional diet, followed by six days on an all-organic diet, and found average reductions of more than 70 percent in both the adults and children.

These reductions were achieved after just three days on the organic diet, which is in line with animal studies showing most glyphosate leaves the body after five to seven days, though a smaller amount remains in and is eliminated more slowly from bone and bone marrow.

Published today in Environmental Research, the paper is the most robust examination of glyphosate levels in people after a dietary switch and provides important information about how people can avoid exposure to the herbicide, the main ingredient in Bayer’s weed killer Roundup. The findings are timely as Bayer, which purchased Roundup-maker Monsanto in 2016, recently agreed to a $10 billion payout to tens of thousands of current and potential future lawsuits from groundskeepers and farmers claiming they contracted non-Hodgkin lymphoma after using Roundup.

While other studies have tested for glyphosate in cereals and other foods on grocery shelves, few have measured the pesticide in human bodies related to diet.

“Despite glyphosate being in such widespread use in agriculture, in our yards, on school playgrounds and in city parks worldwide…the U.S. government has done so little to understand our exposure,” Kendra Klein, study author and senior staff scientist at Friends of the Earth, told EHN.

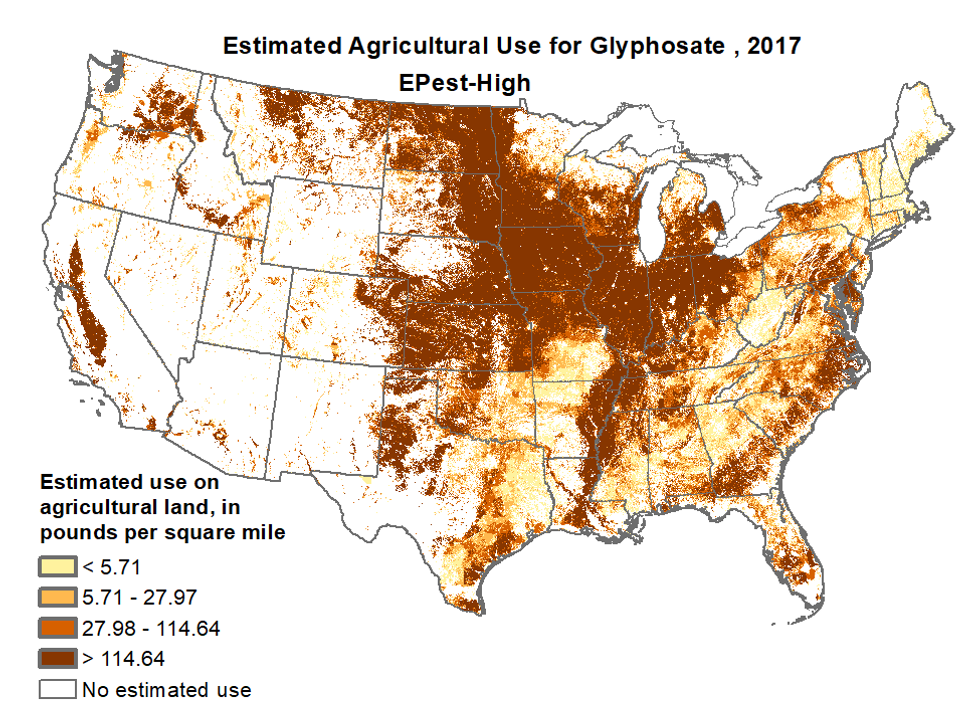

Glyphosate use has risen dramatically since 1996 when the first genetically-modified (GMO) “Roundup Ready” crops were introduced. Some 280 million pounds of glyphosate are sprayed each year in the U.S., on approximately 298 million acres of cropland, largely for GMO corn, cotton and soybeans. Another 26 million pounds are sprayed on public parks, rights of way and in gardens.

The researchers found glyphosate and AMPA in 94 and 97 percent, respectively, of the urine samples tested. A total of 158 urine samples were collected, which allowed the researchers to find statistical significance in the results even though the study group was small.

Children had significantly higher levels of glyphosate and AMPA in their urine than adults during both the conventional and organic diet phases of the study.

Glyphosate levels in children were about five times higher (1.27 nanograms per milliliter (ng/ml) versus 0.26 ng/ml in adults during the conventional phase, and 0.46 ng/ml in children versus 0.09 ng/ml in children during the organic phase).

Klein said she’s uncertain why the children had higher exposures. “Maybe they’re exposed at schools, or they’re rolling around in the grass at city parks” where glyphosate is commonly used, she said. Kids also have more exposure per pound of body weight, and they might metabolize the herbicide differently than adults, she said.

“Growing up with this kind of chemical in their body will harm them,” Sharyle Patton, director of Commonweal Biomonitoring Resource Center and a study author, told EHN. “It’s a tragedy,” she said.

Emerging science links glyphosate to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, hormone disruption, kidney disease, changes in the gut biome, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded that glyphosate is a probable carcinogen, and an international group of scientists later concurred with that finding. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, however, continues to assert the herbicide poses no public health risk.

Meanwhile, Bayer has been negotiating settlements with several plaintiffs who alleged they developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma from exposure to Roundup and other herbicides made with glyphosate.

“It’s egregious that our government is allowing pesticide corporations to profit off of poisoning us when we know that organic farming works. These are chemicals that do not need to be in our bodies,” Klein said. “An entire system is invested in continuing pesticide intensive agriculture, while our farmers are fighting for pennies to do the research they need to support them to expand organic farming.”

Organic works — but doesn’t mean zero exposure

The study is the second of a two-part series analyzing the impact of an organic diet intervention on pesticide levels in urine. The first study, published last year, tested for organophosphates, pyrethroids and neonicotinoids, and the herbicide 2,4-D and found similar results. Both add to a growing body of research demonstrating that an organic diet is an effective way to reduce exposure to pesticides.

To be able to say, “this chemical in just a few days will leave your body if you change your diet, so you can do something about it, that’s great info for people to have,” said Patton.

Glyphosate’s use as a desiccant for drying oats, wheat, garbanzos and other grains and beans just prior to harvesting results in the largest residues on food products, according to Charles Benbrook, coordinator for the Heartland Study, a hospital-based research project investigating the potential link between U.S. midwestern herbicide use and harmful reproductive outcomes. Glyphosate has been approved for many vegetables and fruit crops and has also been found in orange juice, wine and honey.

“One of the interesting questions this research raises, is why were the study participants still eliminating glyphosate in their urine six days after a 100 percent organic diet?” Benbrook, who was not involved in the study, told EHN.

Benbrook said there is so much glyphosate in the ambient environment, soil and water, as well as in grain bins, trucks and food production lines, that it’s likely “impossible to keep organic grains and beans sufficiently separate from parts of the conventional food supply chain.”

Organic crops can also pick up some glyphosate residue, he said, from wind erosion blowing soil particles off a nearby conventionally-managed field.

Study participants may also have had other exposures to glyphosate, such as from spraying in public parks. Animal studies also show that a small amount of the weed killer is excreted more slowly from bones.

Regardless,”this paper serves as a wakeup call for regulators, public health scientists, the food industry and farmers—that whenever a pesticide comes to be used as frequently and as heavily as glyphosate-based herbicides, they’re going to get into all sorts of hidden corners of the environment, and because of that they’re going to show up in the food supply in all kinds of ways that no one ever really anticipated,” said Benbrook.

Banner photo: Children’s visit an organic farm in Southern California. (Credit: Suzie’s Farm/flickr)