Over the course of two years, EHN enlisted the help of scientific advisors to develop a study protocol, obtain approval from an Independent Review Board, ensure that we used proper collection protocol, and analyze and interpret the data for a scientific study on human exposure to chemicals associated with unconventional oil and gas operations in Pennsylvania.

This was a small pilot study that’s not meant to test a hypothesis, but rather to provide a snapshot of environmental exposures in people living near fracking wells and help pave the way for additional research on a larger scale.

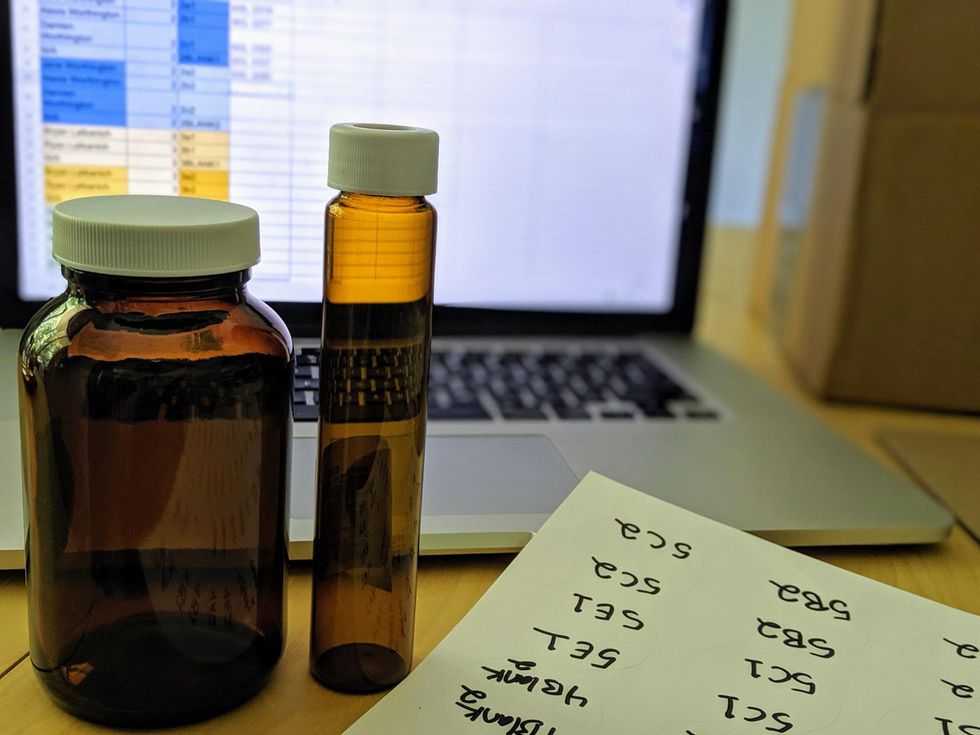

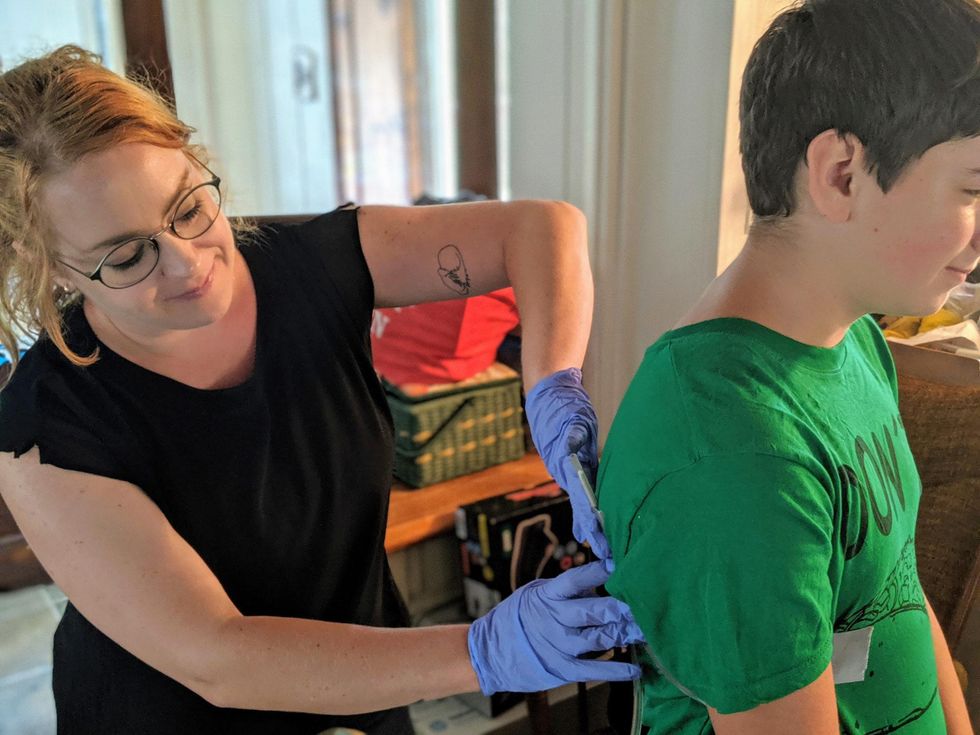

In the summer of 2019, EHN collected air, water, and urine samples from five nonsmoking southwestern Pennsylvania households. All of the households included at least one child. Three households were in Washington County within two miles of numerous fracking wells, pipelines, and compressor stations. Two households were in Westmoreland County, at least five miles away from the nearest active fracking well.

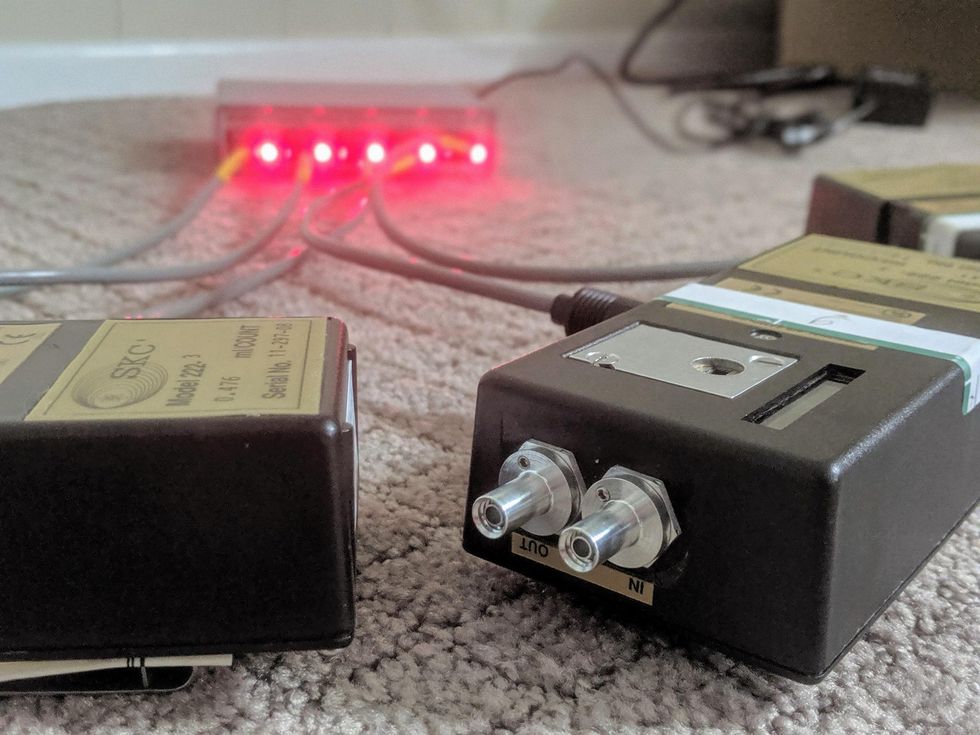

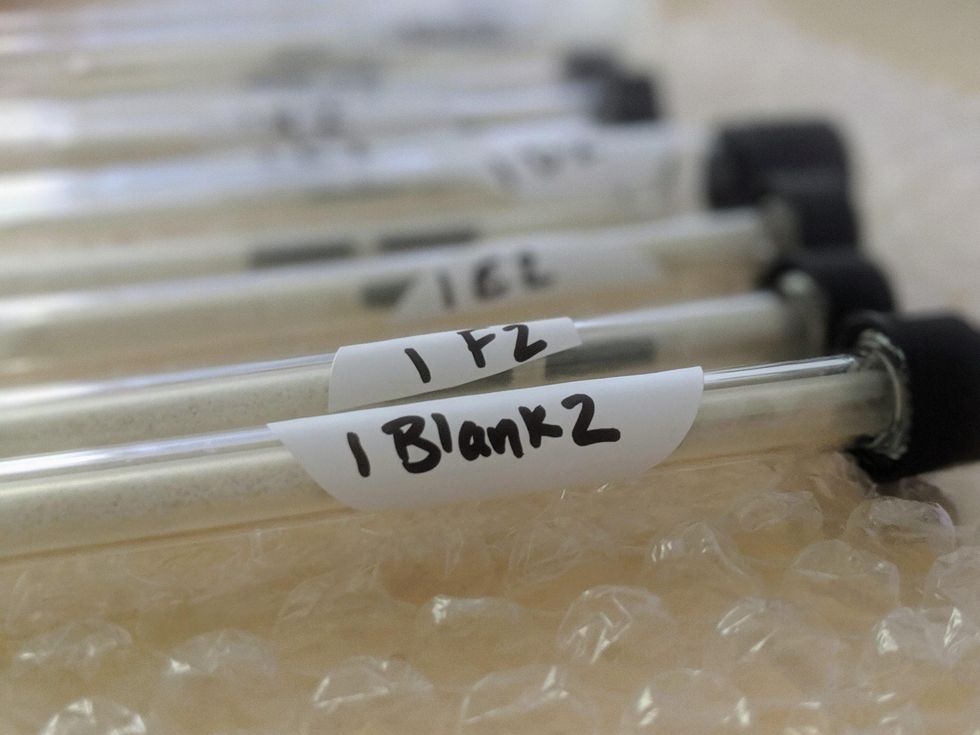

Over a 9-week period we collected a total of 59 urine samples, 39 air samples, and 13 water samples. Scientists at the University of Missouri analyzed the samples using the best available technology to look for 40 of the chemicals most commonly found in emissions from fracking sites (based on other air and water monitoring studies).

To our knowledge, this research marks the first time anyone has investigated whether chemicals emitted from fracking sites in Pennsylvania are making their way into the bodies of families living nearby. It’s also one of very few studies to do biomonitoring (measuring chemicals inside people’s bodies through blood or urine samples) in people living near fracking wells anywhere: Researchers in Wyoming conducted a study similar to ours in 2016, and researchers in British Columbia measured levels of breakdown products for benzene among pregnant adults in a 2017 study.

The shortage of research into this topic makes data analysis difficult, since there isn’t an abundance of scientific literature available to compare our findings against. EHN shared data and consulted with the people involved in both of those studies and learned that in many cases, the levels of chemicals we detected in the bodies of Pennsylvania families were higher than those measured in people in Wyoming and British Columbia.

Monitoring children

EHN’s research is also unique in that we looked at more children than adults. Typically children haven’t engaged in any of the lifestyle behaviors that often lead to adults having high levels of unwanted chemicals in their bodies—smoking, drinking, varnishing floors, driving heavy machinery—so, in general, looking at children provides a clearer view of potential environmental exposures.

Preliminary data analyses indicate that among our study participants, living closer to fracking wells meant people were statistically more likely to have certain compounds in their urine. These included 1,2,3-trimethylbenzene, 2-heptanone, and naphthalene.

Exposure to these compounds is linked to skin, eye, and respiratory issues, gastrointestinal illness, liver problems, neurological issues, immune system and kidney damage, developmental issues, hormone disruption, and increased cancer risk.

Some chemical exposures aren’t detectable in urine if the body has already broken them down, so we also looked for breakdown products for harmful chemicals.

Certain biomarkers for industrial chemicals also showed up at higher levels in people who live closer to fracking wells, including 4-methylhippuric acid, which is produced when the body breaks down xylenes, and phenylglyoxylic acid, which is produced when the body breaks down ethylbenzene and styrene. Exposure to xylenes, ethylbenzene and styrene are linked to skin, eye, and respiratory issues, gastrointestinal illness, organ damage with chronic exposure, hormone disruption, and increased risk of cancer.

What we looked for

Some of these biomarkers have sources other than these chemicals. For example, trans, trans-muconic acid is a biomarker for benzene, but eating sorbic acid (a common food preservative) also produces trans, trans-muconic acid. Hippuric acid is a biomarker for toluene, which can damage the nervous system or kidneys, but it’s also formed when the body processes tea, wine, and certain fruit juices.

As a result, we expect to see a certain amount of these compounds in everyone—which is why, throughout this series, we compare our data against the levels of these breakdown products in the average American using U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Data analysis is ongoing, but so far we have not found chemicals in our air or water samples that were more likely to show up among people who live near fracking sites than they are among people who live further away. As additional data analyses become available through our scientific advisors and partners, we will continue to publish updates on our findings.

For reference, here are comprehensive lists of the compounds we looked for in air, water, and urine samples:

Parent compounds screened for in urine samples

1-methylnaphthalene

1,2,3-trimethylbenzene

1,2,4-trimethylbenzene

1,2,4,5-tetramethylbenzene

1,3,5-trimethylbenzene

2-ethylhexanol-1

2-heptanone

2-methylnaphthalene

2-pentanone

4-heptanone

4-isothiocyanate-1-butene

allyl isothiocyanate

alpha-pinene

benzene

butylcyclohexane

carvone

cumene

d-limonene

decane

dodecane

ethylbenzene

ethylcyclohexane

heptane

m/p-diethylbenzene

m/p-ethyltoluene

m/p-xylene

methyl salicylate

methylcyclohexane

n-propylbenzene

naphthalene

nonane

o-diethylbenzene

o-xylene

octane

pentadecane

styrene

tetradecane

toluene

tridecane

undecane

Biomarkers screened for in urine samples

2-hydroxy-n-methylsuccinimide (parent compound: n-methyl-2-pyrrolidone)

2-methylhippuric acid (parent compound: xylene)

2-pyrrolidone (parent compound: n-methyl-2-pyrrolidone)

3-methylhippuric acid (parent compound: xylene)

4-methylhippuric acid (parent compound: xylene)

alpha-naphthyl glucuronide (parent compound: naphthalene)

beta-naphthyl sulphate (parent compound: naphthalene)

hippuric acid (parent compounds: toluene and cinnamaldehyde)

mandelic acid (parent compounds: ethylbenzene, styrene)

phenylglyoxylic acid (parent compounds: ethylbenzene, styrene)

trans, trans-muconic acid (parent compound: benzene)

Compounds screened for in air samples

1-dodecanol

1-methylnaphthalene

1,2,3-trimethylbenzene

1,2,4-trimethylbenzene

1,2,4,5-tetramethylbenzene

1,3,5-trimethylbenzene

2 ethyl 1 hexanol

2-heptanone

2-methylnaphthalene

4-heptanone

alpha-pinene

benzaldehyde

benzene

butylcyclohexane

cumene

d-Limonene

decanal

decane

dodecane

ethylbenzene

ethylcyclohexane

heptanal

hexanal

m/p-diethylbenzene

m/p-ethyltoluene

m/p-xylene

methyl salicylate

n-nonane

n-octanal

n-propylbenzene

naphthalene

o-diethylbenzene

o-xylene

octane

pentadecane

styrene

tetradecane

toluene

tridecane

undecane

Compounds screened for in water samples

1-methylnaphthalene

1,2,3-trimethylbenzene

1,2,4-trimethylbenzene

1,2,4,5-tetramethylbenzene

1,3,5-trimethylbenzene

2-ethylhexanol-1

2-heptanone

2-methylnaphthalene

2-pentanone

4-heptanone

4-isothiocyanate-1-butene

allyl isothiocyanate

benzene

butylcyclohexane

carvone

cumene

d-limonene

diethylbenzene Isomer

diethylbenzenes

ethylcyclohexane

ethylbenzene

heptane

m-ethyltoluene

m-xylene

methylcyclohexane

n-decane

n-dodecane

n-nonane

n-undecane

naphthalene

o-xylene

octane

p-ethyltoluene

p-xylene

pentadecane

propylbenzene

styrene

tetradecane

toluene

tridecane

Have you been impacted by fracking? We want to hear from you. Fill out our fracking impact survey and we’ll be in touch.

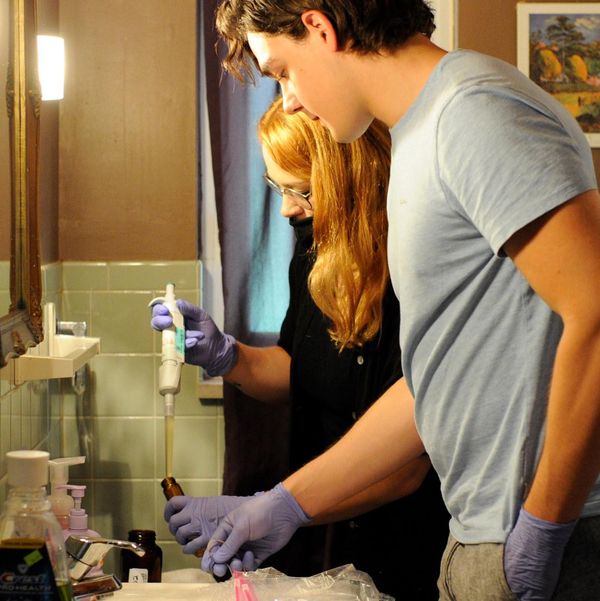

Banner photo: EHN reporter Kristina Marusic and former Southwest Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project intern Mason Secreti transfer urine samples into vials to be frozen and overnight and shipped to a laboratory in the summer of 2019. (Credit: Connor Mulvaney for Environmental Health News)