A half year after the train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, independent researchers say their work contradicts the government narrative that the area is safe and residents say they are sick and are navigating the causes of their symptoms without any reliable guidance.

Meanwhile, public policy advocates are fatalistic about efforts to increase regulation of freight train and petrochemical industries.

These were the main takeaways from a Cancer Free Economy Network online symposium last week where experts and residents gathered to provide updates on the ongoing environmental and health challenges in the wake of the spill.

Days after a Norfolk Southern train carrying an array of toxic chemicals — some of which the EPA links to cancer, organ damage and irritation to the skin, nose and eyes— caught fire and derailed in this town of about 4,700 on Feb. 3, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine proclaimed the town safe. Still, some residents still have not returned and many report nausea, rashes and breathing problems, symptoms that independent researchers who spoke at the forum are in the beginning stages of documenting and tracing.

“Sadly, the first communication coming out was telling people that now the danger had passed and things were safe,” said Ted Schettler, science director at the nonprofit Science and Environmental Health Network and moderator at the event, “and now we’re learning six months later that things are not safe and we know that we need a more prolonged response to this disaster.”

Norfolk Southern is still working to remove soil and replace train tracks and some residents worry they are kicking up clouds of toxic dust.

Representatives for Gov. DeWine, Norfolk Southern, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which leads the remediation response, were not immediately available for comment.

East Palestine residents say they are sick, distrustful

The state has never amended its stance that the town is safe to live in, and contractors for Norfolk Southern have tested and cleared many individual homes in the area. But members of the East Palestine Unity Council, an advocacy group of residents of the surrounding area, say that they can’t reconcile these messages with their own experiences and those of their neighbors.

Amanda Kenner, who lives four miles from East Palestine in Darlington, Penn., said her four-year-old’s asthma has worsened and both she and her eight-year-old have also developed asthma, which they did not have before the derailment.

She said these symptoms worsen during peak activities for the Norfolk Southern-lead clean-up effort that’s supposed to put this disaster behind the communities.

“You may be feeling fine for a few days, maybe a week, if that,” said Kenner, “and then when they start digging in these areas that are heavily contaminated, it gets into the air, and then people get sick all over again.”

When asked about the possibility that the clean-up was kicking up harmful chemicals, a spokesperson for the EPA told Environmental Health News that the agency “has not detected any significant and sustained levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in community air monitoring since the evacuation order was lifted on Thursday, February 9.”

“We were told that it’s safe and our pushback on that is safe is very subjective,” said Hilary Flint, vice president of the Unity Council. “It’s not safe for everyone.”

Misti Allison, public health lead for the Unity Council, likens reactions to conditions in East Palestine to experiences with COVID-19: It affects people differently. “[W]e all know people who have never had COVID before. We know people who maybe just had the sniffles. We know people who were in the I.C.U.”

The residents said they have to navigate their symptoms themselves and a trickle of early findings from independent researchers have increased their anxieties.

Researchers seek out environmental answers in East Palestine

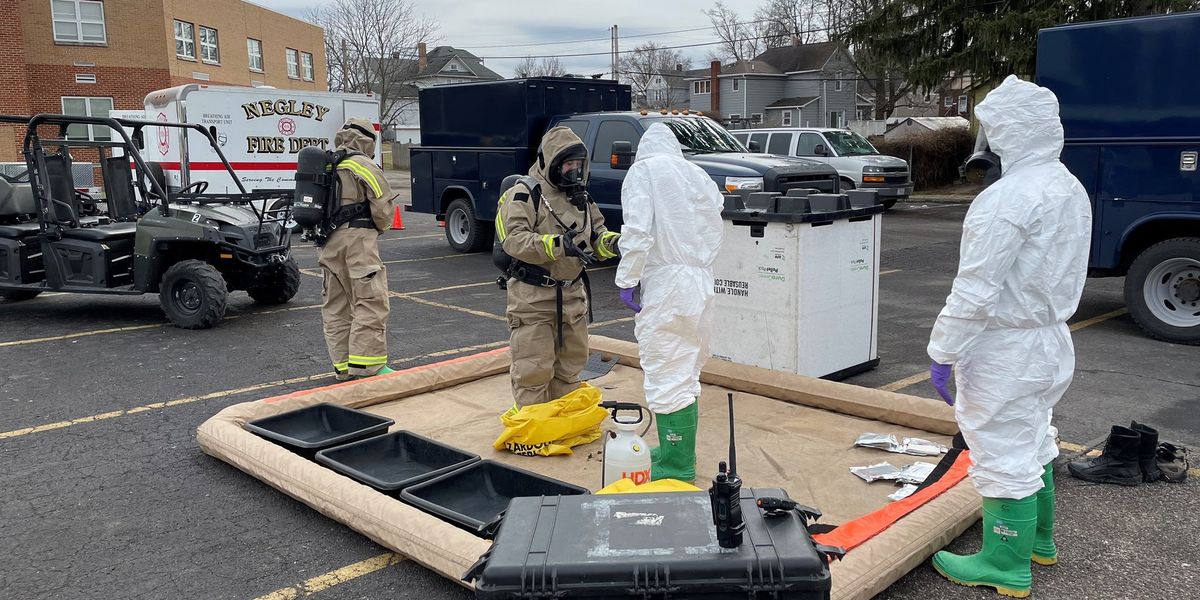

In the days after the derailment, a parade of independent researchers arrived in East Palestine to track the environmental and health effects of the chemical spill and the controlled burn that unleashed a plume of black smoke over town. Two of them said their findings consistently contradict official narratives.

Andrew Whelton, an environmental ecological engineering professor at Purdue University, started taking soil and water samples in March. His goal, he said, was tracing the paths of vinyl chloride, dioxins and other chemicals, particularly through the creeks that run under buildings.

He said devices used by Norfolk Southern contractors were not attuned to the specific chemical dangers. “These devices should always generally be backed up by chemical specific testing,” he said.

Indoor testing, he said, “wasn’t thorough and it wasn’t done in a way that they could find the health risks that they needed to find.” As a result, some buildings marked as safe “remained contaminated for four and a half months after the disaster and contamination had likely gotten trapped inside and never was completely removed.”

Erin Haynes, a professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the University of Kentucky, launched a tracking study of symptoms reported by residents in and around East Palestine. She and her team have recruited about 350 people.

They have reported headaches and skin, throat and nasal irritation months later, and 80% said their symptoms were still present. Almost 40 percent reported stress levels matching post-traumatic stress disorder, she said.

They also tested blood and urine samples, but do not have results yet.

Whelton also said that the timeline for funding research by academics does not sync up with researchers’ needs to track data quickly in a disaster like the derailment. “We’re talking three months to four months after you submit an application to get that money,” he said.

He said he’s conducting his study without funding. “I went thousands of dollars in debt, because we got in a van and drove across Ohio to start helping without a way to pay for it.”

Political players express doubts in East Palestine

In the day’s final panel on public policy and ideas for preventing future derailments, Pennsylvania Sen. Katie Muth, a Democrat who represents an area outside Philadelphia, painted a bleak landscape of a political system manipulated by deep-pocketed industries.

“From drilling wells to extraction to waste disposal our laws protect industry from any accountability,” she said, “and that’s the state and federal law.”

The chemical and transportation industries are cozier to Republicans, she said, but unions whose members hope to benefit from drilling also hamper Democrats.

Glenn Olcerst, general counsel for the advocacy group Rail Pollution Protection Pittsburgh, echoed her pessimism. He cast doubt on the Railway Safety Act, federal lawmakers’ response to the East Palestine disaster. The law would mandate new safety precautions for trains and allot $27 million for research on tank car safety.

“Although that all might sound reasonable to the general public, rail workers and their unions know better,” said Olcrest. “They have zero confidence that the [Federal Rail Administration] is going to act in the public interest, because they know that agency is administered and staffed by former railroad and petrochemical executives and lobbyists who have a long history of some burning rail safety, issuing waivers and serving the rail industry’s agenda.”

Jacquelyn Omotalade, national director for climate investments for the progressive group Dream.Org, had a sunnier view. She said that, while lobbying in D.C., she’s had receptive audiences with lawmakers of all ideologies because the broad idea of environmentally clean communities has universal appeal.

“The reality is that we all want clean water and air, right?” she said “All of us want to have happy, healthy families just as a basic human right. We all want to live in a space that is safe and safe from a broad perspective, right? Like that is across party lines.”