“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.”

Octavia Butler wrote this as an epigram for the never-published third book of her“Parable Series: Parable of the Trickster. She did not live long enough to finish this work, but her words echo on. While she’s been considered a literary giant for decades, her work has recently seen a resurgence and many of her books are being adapted for the screen by some of the industry’s biggest stars. Apparently, something about a global health pandemic, racial justice reckonings, and impending climate doom has lots of people thinking that maybe Octavia Butler was on to something.

In addition to making uncannily accurate predictions about the world we currently live in, Butler invited us to write ourselves into the worlds we want to see. Right now, there’s a lot to be pessimistic about, to worry about, to want to ignore or wish away. For people of color, poor people, immigrants, and marginalized groups, however, just the chance to imagine better realities can itself be elusive and inaccessible. As Dr. Ebony Thomas puts it when reflecting on her own experience growing up as a Black girl in Detroit, “the existential concerns of our family, neighbors, and city left little room for Neverlands, Middle-Earths, or Fantasias.” One must face “reality” in order to survive.

But what would it look like for us to “write ourselves in” to new realities? Perhaps under “new suns”?

This essay is part of “Agents of Change” — see the full series

This was the sort of question that youth interns at Philadelphia’s Sankofa Community Farm were presented with in the summer of 2019. Sankofa is a community-driven farm with a focus on youth development and engagement, with internship programs that offer local youth the opportunity to engage in intergenerational learning about urban agriculture and food sovereignty. I joined as a community gardener a couple of years ago and began supporting the youth programming soon after. On a summer day in 2019, interns were in a workshop discussing what literary genres like speculative fiction and Afrofuturism could offer food justice and climate activism efforts. They were also invited to write their own stories.

I was technically supposed to be there as an “outside observer” doing research. I was conducting qualitative observations and taking fieldnotes for an evaluation report for the farm. I was interested in the research, but I was also quietly fangirling over some of the stories the young people were sharing. My background as a language arts teacher, combined with my childhood aspirations of being a writer, made it impossible for me to see this experience as just something to write up for a report.

One story, about a young orphan on a spaceship who wakes up with seeds in her hair and no idea how they got there, caught my attention. Even as I continued writing the evaluation report, I kept thinking about the characters in this story and in others. I wanted to know how they were doing, what they wanted, where they were going. I wondered what it would look like to bring them to life.

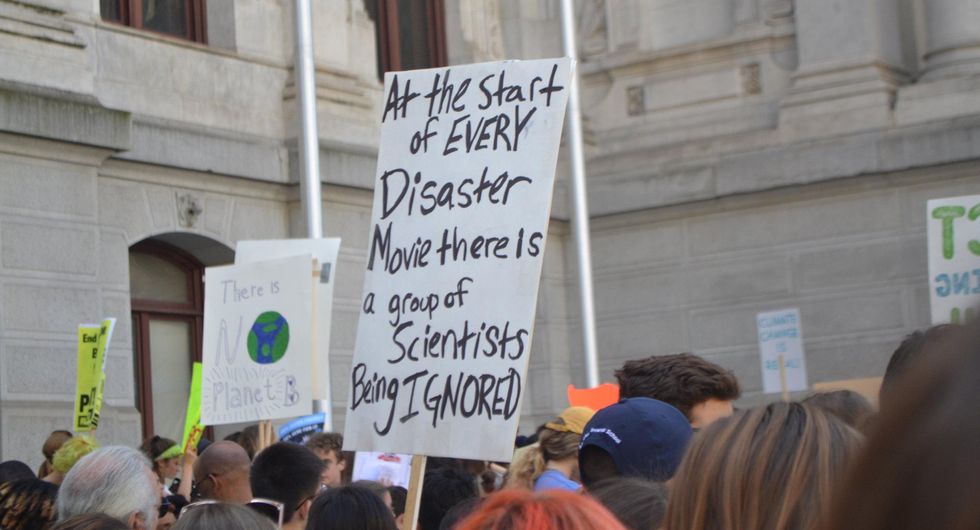

As youth climate activist Mitzi Jonelle Tan writes, “we need a new language to communicate about the climate crisis and justice — one that embraces creativity and culture“. She talks about how youth climate activists are leveraging the arts in ways that recognize their cultural histories as important guideposts for navigating the future. Hearing stories from youth writers at Sankofa sparked an interest in how creative storytelling about space and time travel can help reclaim and remix historical narratives and call into existence reasons for hope in the face of terribly bleak realities.

Creative writing and food justice

Fast forward two years and I’m co-facilitating a Food Justice Writing workshop with two of the youth interns who wrote the story about the girl with seeds in her hair. With help and guidance from local artists and storytellers, and support from local arts and research organizations, we have embarked on our fist collaborative piece: a speculative fiction screenplay that centers on the history and relevance of okra in Black food traditions and histories. Okra is one of the botanical connections to the African continent that enslaved peoples brought with them. It has stood the test of time, becoming a staple in African diasporic cuisines, and a vehicle for Afro-Indigenous culinary and agricultural traditions, across the globe. Prominent food scholars and activists have written about its significance in their personal family histories, in our national culinary history, as well as in our botanical and agricultural history. The Food Justice Writing Group brings together what we are learning from stories like these, and from our own experiences with the land, food, and community, to write ourselves into the worlds we want to create. It’s a lot of fun, and a lot of work.

Interested in our screenplay? Below is the edited audio from a table read of our first scene. I hope you enjoy the low budget sound effects as much as we enjoyed making them.

If you took the three and half minutes to listen to the (very rudimentary) table read, are you on the edge of your seats?! We hope so, but it’s ok if you’re not. As much as we want this story to connect with and captivate audiences, this project is just as much about the process as it is about the product. We excavate the intricacies of our own lived realities to add depth, weight, and texture to the imagined universe that Ada, our main character, occupies. As we write, we learn about composition, storytelling, research, the film industry, climate change, teamwork, food justice, and more.

Creativity in climate communication and education

There is significant interest in creative approaches to climate storytelling. Within the film industry, Doc Society and Exposure Labs recently collaborated on a Climate Story Lab to facilitate global partnerships and create resources that support compelling and imaginative storytelling around infrastructure, policy, advocacy, and education for climate justice.

The Black List, Natural Resources Defense Council, and Redford Center have recently created a Climate Storytelling Fellowship, which, among other things, aims to promote a strand of climate storytelling that shows “alternative futures, beyond the cliches of climate disaster/dystopia.” The Redford Center also launched a learning and storytelling initiative that invites students and educators to collaborate on stories that elevate visions for “a more just, hopeful, healthy world.”

Opening possibilities to explore alternative futures is an important step for climate and environmental education. While not a panacea, opportunities to engage in speculative fiction writing, or any sort of imaginative writing, can help readers better understand the complexity of climate change, support teacher confidence in working towards education for sustainable development goals, provide a safe space for learners to rethink and challenge current structures, and help mitigate the burden of despair young people sometimes experience with increased knowledge of climate change.

Not new, and not an escape

The creative search for “new suns,” perhaps paradoxically, isn’t new at all. Octavia Butler published her first novel back in the 1970’s. Around the same time, across the Atlantic, Ken Saro Wiwa was using satire to challenge corrupt environmental policies instigated by the national government and large multinational organizations. Indigenous peoples across the globe have used storytelling to pass down knowledge of the natural world as well as to present alternative futures for centuries. We have had this ancient technology, that both roots us in deeper understandings of our lived realities and transports us to realities we may never see, for a very long time.

This long tradition has taught us that “finding new suns” is not always about an escape. While developing Ada’s story, one of the youth writers in our group reminded us that even if we find another planet to flee to if this one is rendered inhabitable, we’ll still be human, which means there’s just as much of a chance that we will let the worst parts of ourselves get the best of us and continue to wreak havoc wherever we go. Already, “billionaire space races” are showing that inequity and injustice are galactic phenomena, and scientists and storytellers alike have warned us that there is still so much work to be done here if we are to keep ourselves from replicating these problems elsewhere.

Building Ada’s world, therefore, is not about finding new realities so that we can absolve ourselves of the mistakes we have made. Nor is it about ignoring the science and the truth of the world we live in. Dr. Kathleen Gallagher writes of “creative resilience,” through which young people can create “an imagined world in order to understand the very real, material one we occupy.” In order to write creatively about food cultivation, climate change, and social justice, we need to understand how they operate in the world we live in. Imagining a better future, therefore, requires keen and purposeful observations of the present. It requires science.

Our story is still being written. Metaphorically this may be true for us all, but I mean this quite literally in the context of the Food Justice Writing Group. We still don’t have a title yet and we don’t know exactly where Ada’s story will take us — whether it will help us better understand the sun that already sustains us, help us find new suns, or a combination of both. We also still have like 30 scenes to complete…collaboratively writing takes time. Maybe we’ll finish the script, maybe we won’t. Maybe it will get turned into a big Hollywood blockbuster (lowkey shameless plug here) and maybe it won’t, but the point is that we keep writing, we keep imagining, we keep learning, and we keep working to make this reality, here and now, a better version of itself.

OreOluwa Badaki is a Ph.D. Candidate and Instructor in the Literacy, Culture, and International Education Division on the College of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education. OreOluwa is a lead researcher with the Southwest and West Agricultural Group in Philadelphia, and recently served as Co-Director for the Collective for Advancing Multimodal Analysis Arts on the University of Pennsylvania. She might be reached at obadaki@upenn.edu or @OreOluwaBadaki.

This essay was produced through the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice fellowship. Agents of Change empowers emerging leaders from historically excluded backgrounds in science and academia to reimagine solutions for a just and healthy planet.

Banner photo: Youth writers in working on journal entries before the start of a Food Justice Writing Group session. (Credit: OreOluwa Badaki)