Science and the U.S. Supreme Court are on course to become oil and water, much to the joy of Big Oil and to the dread of those who support actions that protect our planet.

That’s the implication of the reasoning of Justice Samuel Alito in his leaked draft of the high court’s potential ruling to restrict reproductive rights by overturning Roe v. Wade.

Justice Alito wrote that Roe v. Wade should be struck down because the constitution “makes no reference to abortion.” With all the subtlety of a jackhammer, he asserted, “Until the latter part of the 20th century, there was no support in American law for a constitutional right to obtain an abortion. Zero. None.”

In his draft ruling, Alito conferred credibility and salience to British anti-abortion laws of the 17th and 13th centuries. Calling them “eminent common-law authorities,” he quoted the primitive wisdom of British jurists such Henry de Bracton, Sir Edward Coke and Sir Matthew Hale. De Bracton classified women as inferior; Coke and Hale believed witches can be executed; and Hale wrote that husbands cannot be accused of raping their wives.

Justice Alito went on to repeatedly cite how most U.S. states criminalized abortion during the 19th century—the same century that began with slavery and ended with codified segregation and general denial of women’s suffrage. He said past criminal sanctions on abortion refute “the notion that the abortion liberty is deeply rooted in the history or tradition of our people.”

Broader implications

The broader implications of glorifying the certitude of jurists who wrote and defended laws in eras where white men literally controlled Black bodies and treated white women as second-class citizens are terribly easy to imagine. If Alito’s draft remains the foundation of the court’s final ruling, then he is also likely prepared to let white-run industry off the hook for fouling the land, air, rivers, and lakes, poisoning communities, which today are disproportionately of color.

Given that the importance of science, let alone law guided by science, is barely mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, and then only in reference to patents and copyrights of inventions, it bodes especially ill for environmental law, climate-related law, and for science itself.

Environmental laws could easily be overturned if Justice Alito were to employ a similarly fossilized premise that “until the latter part of the 20th century, there was no support in American law for a constitutional right.” Outside of bird protection acts of the early 20th century, protections for water, air and the atmosphere are a late 20th-century development, created in the wake of Rachel Carson’s 1962 treatise on pesticides, Silent Spring. The landmark Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Toxic Substances Control Act, and the Environmental Protection Agency were all enacted or created in the 1970s.

Fossil fuel and chemical polluters, business lobbyists and conservative private land interests have fought these laws and the EPA since their inception and they made fresh headway during the Trump administration, which undertook a widespread effort to gut environmental protections and slashed staffing of the EPA back to levels of the 1980s. Trump is out of office, but he left behind a 6-3 conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court.

If Justice Alito marshals his conservative colleagues against environmental laws as the leaked draft decision in Roe v Wade suggests he has done, there are many opportunities ahead for the court to curtail their reach, the EPA’s authority to use them, and, ultimately, the level to which the nation can fight climate change and environmental injustice.

Climate change on the docket

The Court is expected soon to render its judgment in West Virginia v. EPA. At issue in this case is whether and how the EPA can set standards for carbon emissions at power plants. When the Obama administration attempted to implement the Clean Power Plan, it said that the new standards would fight climate change, create tens of thousands of jobs in renewable energy and avoid up to 3,600 premature deaths from soot and smog.

The coal industry and conservative states want the high court to limit EPA’s powers solely to the regulation of individual power plants. They appear to have a sympathetic ear in Justice Alito. During February’s oral arguments in West Virginia v. EPA, Justice Alito badgered Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar to explain how the government was not overreaching by claiming “the authority to set industrial policy and energy policy and balance such things as jobs, economic impact, the potentially catastrophic effects of climate change, as well as costs.”

Unsatisfied with the answer Solicitor General Prelogar gave, Justice Alito pressed on, sounding like the head of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which ceaselessly fights regulations to control climate gases, saying the controls will cost jobs. Despite the data that has led the Secretary General of the United Nations to call climate change “code red for humanity,” Justice Alito told Solicitor General Prelogar that the EPA was making decisions based on “incommensurable” factors that have no common standard of measure. He asked her, “What weight do you assign to the effects on climate change, which some people believe is a matter of civilizational survival, and the costs and the effect on jobs?”

How far will Alito go?

Justice Alito appears to be so vexed about the EPA’s authority that it is reasonable to be concerned that he might lead the 6-3 conservative majority to overturn Massachusetts v. EPA, the landmark 2007 decision that said the EPA has the authority to regulate carbon dioxide emitted from new motor vehicles. Writing for the majority, Justice John Paul Stevens said gases that fuel global warming “fit well within the Clean Air Act’s capacious definition of ‘air pollutant.’” He emphasized that “The harms associated with climate change are serious and well recognized.”

Justice Alito was a dissenting vote in that 5-4 decision and later explained his decision in a 2017 speech to the right-wing Claremont Institute. “A pollutant is a subject that is harmful to human beings or to animals or to plants,” he said. “Carbon dioxide is not a pollutant. Carbon dioxide is not harmful to ordinary things, to human beings, or to animals, or to plants. It’s actually needed for plant growth. All of us are exhaling carbon dioxide right now. So, if it’s a pollutant, we’re all polluting.”

This, of course, defies the scientific consensus about the damage carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels is doing to the planet. There is now a 99.9 percent consensus among climate scientists that global warming is driven by the spewing of carbon dioxide and other gases. After the Massachusetts v. EPA decision, the EPA under the Obama administration found in 2009 that carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons and sulfur hexafluoride are indeed pollutants which “endanger both the public health and the public welfare of current and future generations.”

Justice Alito has displayed similar cynicism about water protection. In the 2022-23 term, the court will hear Sackett v. EPA, a case in which the EPA required a permit under the Clean Water Act from an Idaho couple that wanted to build a home on land containing wetlands near a lake. The EPA under both the George W. Bush and Obama administrations said hydrologic science clearly connects wetlands to larger bodies of water, even if one cannot see the connections on the surface. In a 2015 report based on 1,200 peer-reviewed publications, the EPA said:

“There is ample evidence that many wetlands and open waters located outside of riparian areas and floodplains, even when lacking surface water connections, provide physical, chemical, and biological functions that could affect the integrity of downstream waters. Some potential benefits of these wetlands are due to their isolation rather than their connectivity.”

Disregarding this science and the fact that the EPA says a third of wetlands are in “poor biological condition,” Justice Alito has signaled that he essentially needs to be able to actually see the water flow from wetlands into lakes on a Google Earth map. He was one of the dissenters in the 6-3 decision in 2020 that held that wastewater pumped into groundwater by Maui County in Hawaii which reached the sea a half mile away was covered by the Clean Water Act. He said permits should be required only “when a pollutant is discharged directly from a point source to navigable waters.”

In the 2006 Rapanos decision, Justice Anthony Kennedy determined that a wetland should have a “significant nexus” such as a navigable lake or river to be eligible for protection under “Waters of the U.S.” But Justice Alito joined Justices Clarence Thomas and Antonin Scalia, as well as Chief Justice John Roberts in saying they would have afforded wetlands even less protection. They would have limited protection to “only those wetlands with a continuous surface connection” to larger bodies of water.

Tyranny of the minority

Justice Alito’s longstanding consistency in wanting to restrict EPA authority makes it transparent where he wants the court to go. In his Claremont Institute speech, he depicted Sackett v. EPA as an example of where the EPA demonstrated the “tyranny” of government agencies that had the power to “make the law, and to enforce the law, and to decide disputes about the application of the law.”

Of course Justice Alito’s views are also tremendously unpopular. A 2019 Pew survey found that two thirds of respondents said the federal government is doing too little to protect water quality, too little to protect air quality, and too little to fight climate change. The same survey found that just 20 percent of the population doubted that humans are causing climate change and some 77 percent say it is time to prioritize renewable energy over fossil fuels.

Justice Alito may think, as he said in his Claremont speech, that people are “of two minds” about climate change or that only “some” people think climate change is a matter of survival. He may think that carbon dioxide is not a pollutant and that wetlands are not vitally connected to rivers and lakes. He may think that—as part of the dissent in Massachusetts v. EPA—the connection between global warming gases from vehicles and loss of coastal land “is far too speculative to establish causation.”

Most people in the United States no longer speculate about any of those things. Care for the environment might not have been deeply rooted in the nation’s laws until the 1970s, but millions of people are now reeling from loss of land, life, and property from extreme climate events. All this appears lost on Justice Alito. Unleashed in the conservative supermajority, all signs point to his desire to lead the high court in a tyrannical siege on science that flies in the face of the environmental wishes of the majority in the United States.

Derrick Z. Jackson is on the advisory board of Environmental Health Sciences, publisher of Environmental Health News and The Daily Climate. He’s also a Union of Concerned Scientist Fellow in climate and energy. His views do not necessarily represent those of Environmental Health News, The Daily Climate or publisher, Environmental Health Sciences.

This post originally ran on The Union of Concerned Scientists blog and is republished here with permission.

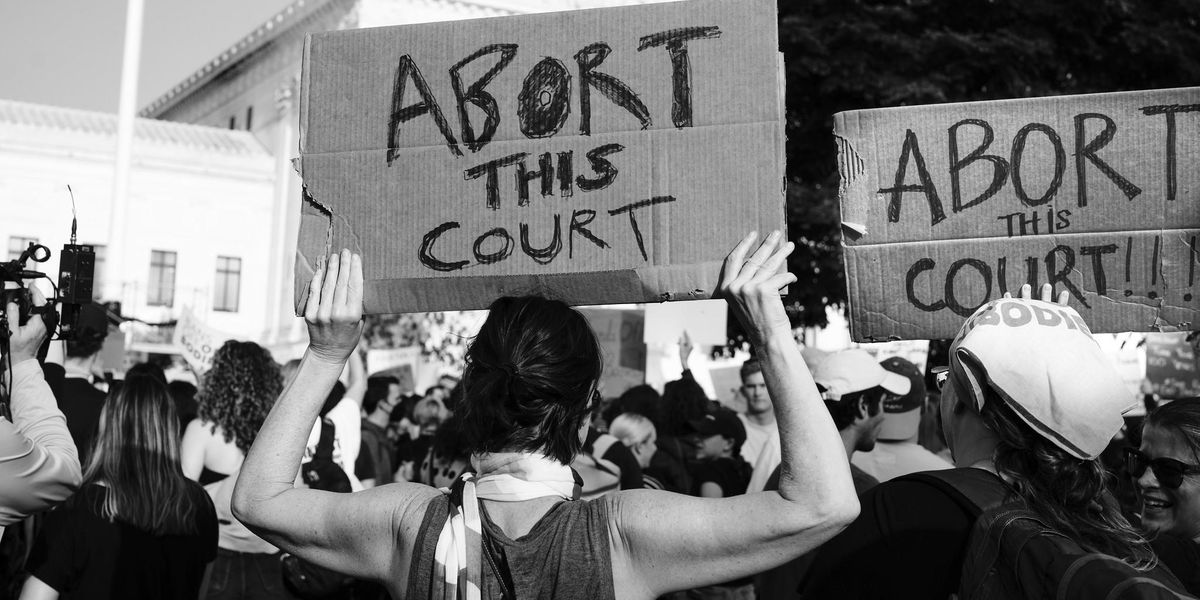

Banner photo: Rally after the leaked Supreme Court opinion, May 3, 2022. (Credit: Victoria Pickering/flickr)