In May 2020, Greg Johnson went to Little Saint Germain Lake in northern Wisconsin to spear walleye.

He was with Carl Edwards and Leon Valliere, friends from his tribe, the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, and a visiting friend, Stephanie Stevens. The four loaded their boat and set out. At the first fork, Johnson told Edwards to steer left—remembering the last time he went right someone threatened to kill him.

They entered the next bay and saw a house alive with lights and music. The group heard yelling, making out the words “fish,” and “get off the lake” above the motor noise. Then they heard a shot.

“It was shocking,” Johnson told EHN. “We knew what was up…the gunshot was aimed at us.”

Johnson and his group were practicing their treaty-affirmed rights to harvest fish. Tribes across the U.S. have the right to hunt, fish, and harvest both on and off reservations. These rights are stated and reaffirmed in treaties and court cases since the 1800s. EHN spoke with tribal members in the Great Lakes region who said they commonly experience harassment because non-Natives believe they are exploiting resources, breaking rules, or getting special treatment—all of which show a misunderstanding of treaty rights. Unfortunately, unlike the incident with Johnson and his friends, these cases are inconsistently reported across the country, if they’re reported at all.

Jim Kelsey, the man who fired the gun, was arrested—according to the police report, he was drunk and claimed he was trying to shoot a red squirrel. In reference to possibly spending the night in jail, the police report also records him saying, “I don’t want to get the Covid, especially if the Indians are there,” as he was being handcuffed. In January Kelsey was charged for use of a firearm while intoxicated, and nothing more.

He was let off with community service and a $344.50 fine.

A fraught history

Starting in the 1800s, the U.S. government signed treaties with tribes around the country. In these treaties, written up after more than 100 years of conflicts, tribes ceded large portions of their land, agreeing to live on reservations so long as they could maintain the rights to co-manage the land and continue to harvest (fish, game animals, medicines, plants) in their traditional areas off-reservation.

“It’s not like these rights to harvest and co-manage these resources in our areas were just handed to us,” Dylan Jennings told EHN. Jennings is a member of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, and the director of public information for the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), an organization that represents 11 Ojibwe tribes in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. GLIFWC advises tribal individuals as well as the non-tribal community on natural resources.

In the Great Lakes region, tribal harvesting includes wild rice, herbs, and wood; hunting waterfowl, deer, bear, elk, otter, bobcat, and turkey; and fishing walleye, muskellunge, and trout, among others. Harvest rights also look different across the U.S., as tribes have to frequently negotiate with states to determine the scope of their rights. For example, the state of Michigan and five tribes are renegotiating the Great Lakes Consent Decree determining harvest details in parts of the Great Lakes, according to a spokesperson from Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources.

Treaty rights often predate states. For instance, the Chippewa (Chippewa is synonymous with Ojibwe) signed eight treaties between 1795 and 1889, but Wisconsin became a state in 1848. Once state governments formed, Jennings said it added “another level of complexity.”

“States start to impose their own laws on harvesters, tribal members,” he added.

Courts affirm rights

Throughout the 1900s, tribes across the U.S. took states to court, arguing that attempts to bar them from harvesting was a breach of federal treaties. The tribes won landmark cases, including:

- United States v. Winans (1905): A private commercial fishing company barred the Yakima people from crossing their land to access fishing spots on the Columbia River. The case reached the Supreme Court, which ruled that the company could not bar the Yakima from traversing their land.

- Menominee Tribe v. United States (1968): The Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that treaty rights no longer applied to the Menominee Tribe in Wisconsin since the federal government stopped recognizing them in the 1940s. The Menominee appealed to the federal Supreme Court which reversed the decision, ruling that Wisconsin could not interfere with the tribe’s hunting and fishing.

- Voigt Decision (1983): In 1974, two members of the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Band were arrested for spearfishing off their reservation. In 1978, the tribe took the state of Wisconsin to court, which ruled against the Ojibwe. The tribe appealed, and in 1983, the court ruled in favor of the Ojibwe, reaffirming their inherent rights to hunt, fish, and co-manage the land.

But harassment persists.

Troubling trends in tribal harassment

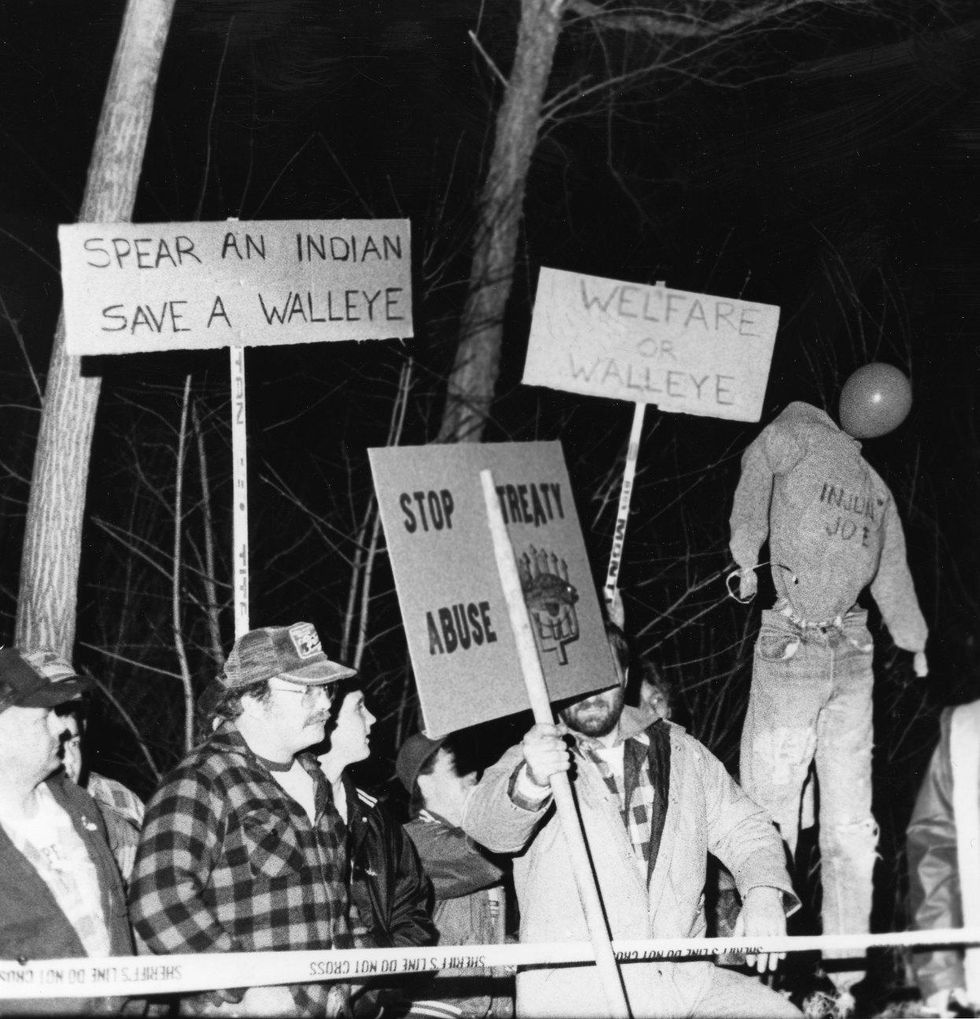

Tribal harassment spiked in the 1970s and 1980s, when non-Natives publicly protested against Indigenous rights and groups like Stop Treaty Abuse and Protect Americans’ Rights and Resources circulated anti-Native literature.

Kathryn Tierney, a tribal attorney of 47 years, works with the Bay Mills Indian Community in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and the Chippewa Ottawa Resource Authority, a governing body representing five Michigan tribes in harvest treaty rights. Tierney told EHN “there were pipe bombs, rifle shots…it was god awful scary.”

GLIFWC has

documents from the 1970s and 1980s showing ugly anti-Native rhetoric: an op-ed comparing fish spearers to a “a thief in the night;” protestors organizing rallies at boat landings with signs saying things like “Welfare or Walleye” or “Save a walleye…spear an Indian;” and mailers advertising a Native American hunting season.

Michael Isham, GLIFWC’s executive administrator and member of the

Lac Courte Oreilles

Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, has been with GLIFWC since the 1980s, when he was an intern still in college. He said in recent years there have been troubling signs of a resurgence, as more people share stories of harassment during community meetings.

GLIFWC records include 47 “off-reservation serious incidents” from 2004-2020, 10 of which are from 2020. The 2020 incidents include a tribal member having their tires slashed while fishing, tribal members’ fishing equipment getting thrown into lakes, and “firearms discharged.”

Other incidents from recent years include reports of tribal members hearing multiple gunshots while fishing; strobe flashlights pointed at tribal spearfishermen; and rocks thrown at tribal members.

Doug Craven, natural resources director for his tribe Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians in Michigan, handles harvest licenses. As part of the license renewal process, they ask people to report negative interactions they’ve had. Craven told EHN “within probably the last two years, we’ve seen a little bit more of an uptick … stuff that we hadn’t seen for quite a while.”

Craven recalled going fish spearing with his teenage boys and young daughter last year. They all got into the river, but he took his daughter further downstream. “When I came back,” said Craven, “[the boys] were no longer in the water. They were distraught, and I saw a larger, non-tribal individual getting back into his vehicle with his wife.” He asked his sons what had happened, and they told him that the man had yelled at them, intimidating them to get out.

Unfortunately, stories like this are common, but data—at the local or national level—is not. The GLIFWC report was not part of a formal collection, and the list is far from complete, said Johnson. Isham added that GLIFWC is beginning a more formal initiative to track harassment.

Craven’s department also does not keep a formal harassment log.

Johnson said intimidation, or just resignation, also prevents people from reporting.

According to Jennings, when a tribal member experiences harassment and needs to report the case, individuals will usually go through local law enforcement. The different parties that get involved—like tribal law enforcement, or natural resource departments—varies by case.

Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources wrote in an email statement that they have “zero tolerance for harassment of tribal members.”

Wisconsin’s Attorney General Josh Kaul and Department of Natural Resources Secretary Preston D. Cole put out a joint statement this month timed with the start of walleye spearfishing season for tribal members—reminding residents that “tribal members have the clear right to hunt, fish, and gather in the Ceded Territories, and attempts to interfere with that right are illegal.”

Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources would not provide a comment to EHN about tribal harassment and relations, and the Governor of Wisconsin’s office declined all of EHN’s requests for comment.

Attorney Tierney mentioned that there are ways to better the relationships between law enforcement and tribes. For example, sheriffs in certain counties in Michigan are allowed to give tribal officers authority to make arrests off reservation with state-backed authority.

“That creates a significant change in the relationships,” Tierney said, “recognizing that both the county and the tribe have an interest in protecting people from danger.”

But these agreements are made on a county by county basis, she said, and even then, Michigan law has restricted those arrangements to counties that have reservation land within their borders.

Subsistence lifestyle

This harassment impedes people’s ability to maintain millenia-long relationships with the land and wildlife, Nicholas Reo told EHN. Reo is an associate professor of Native American and Environmental Studies at Dartmouth College and a citizen of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Native Americans are a powerful force advocating for the protection of natural resources, he said, and the health of the land also directly impacts the health of their people.

“The subsistence lifestyle is something that not a lot of people understand,” Jennings said.

Most Indigenous people fish and hunt for subsistence, meaning the food is used for nourishment not sport. If a hunter comes back with one deer, “that deer ends up all over the community, feeding multiple families,” Reo said.

“It’s quite amazing … to be able to sit at your dinner table with your family, and to eat these foods that our ancestors have eaten … and to know that you have harvested everything on that plate and put in work for that,” Jennings said.

The idea that tribes are carelessly exploiting natural resources is so backwards, said Craven. Many tribes, like his, have a wanton waste provision written into tribal law where tribal members issue fines to harvesters who don’t utilize the whole resource. These provisions are legally binding and backed by tribal law enforcement. State governments have no such provisions.

Jennings has heard complaints that since treaties were signed in the 1800s, to exercise those rights Indigenous people should only use fishing and hunting methods from those times, without modern technology. But this thinking is misguided, he added, because commercial fishing uses modern technology to harvest on land that was originally tribal, and “the treaties are two-way streets” with no language preventing either party from using the resources they have.

When talking to non-Indigenous individuals about treaty rights, Craven has heard park wardens and local law enforcement say things like “they get to do whatever they want,” “we can’t do anything about that,” or “that’s a special right that they have.” That language, he said, gives the impression that tribes are getting away with something illicit, or that they’ve tricked their way into exploiting resources.

“Those comments, in our opinion, can really embolden non-tribal individuals then to maybe act as if [the government] is on their side,” he said. It frames the discussion as if state officials’ hands are tied, so they can’t stop Native Americans though they’d like to, and non-Natives feel they should deliver justice themselves.

People will say Native harvesting is damaging to the economy and to the land, said Jennings “but over 35 years of data collected proves quite the opposite.”

John Johnson, tribal chairman of Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, and Greg Johnson’s older brother, points to Wisconsin limits and harvest data. Wisconsin sells millions of sports fishing licenses annually, he explained, and each fisherman is allowed to take three walleye per day—one angler could potentially walk away with around 270 fish in a season. “My reservation has 4,000 people and we [fished] 19,000 [walleye]. So what does that amount to? It comes out to 4.5 fish for Native American” for the season, he said. “And they’re telling us we’re the greedy ones.”

Wisconsin DNR estimates back John Johnson’s math—state data suggest that every year sport anglers harvest three to 10 times as many walleyes as tribal spearers from waters in the ceded territory.

Another stark example: Wisconsin just held a wolf hunting season during the last week of February, issuing 4,000 permits for a quota of 200 wolves. But after just three days, hunters killed 216 wolves, and the season closed. John Johnson and other tribal and conservation activists opposed the hunt, wolves are sacred to Ojibwe people, especially since last estimates say there are only around 1,195 wild gray wolves in the state, and the species only recently made it off the endangered list. This is an example of state sanctioned overhunting, said John Johnson, except it’s worse—these animals are vulnerable yet were still overhunted for sport.

Leniency is permission

“Once that judge let [Jim Kelsey] walk, he made it okay to shoot at Natives,” said Greg Johnson—and the $344.50 fine became the price tag.

“[Law enforcement] took the words over one drunk White man instead of four sober community members,” Alexandria Sulainis told EHN. Sulainis is Greg Johnson’s partner and a member of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi and Odawa tribes in Michigan.

John Johnson was frustrated by the court ruling, and sought meetings with Governor Evers and Wisconsin’s DNR Secretary, Preston Cole, to make an appeal, or at least set up measures to prevent this from happening again. Johnson recalled telling Evers “I’m not letting this go.” In response, they told him that until there’s solid evidence of a crime, there’s nothing they can do.

“I think it’s clear that there was harassment and interference of spearing rights,” Vilas County Sheriff Joseph Fath told EHN. But “there was no direct evidence that they saw a weapon pointed at them…or heard shot pellets hit the water,” he added, so they couldn’t prove Kelsey had shot in their direction. “We handled it just like we would any other crime that gets reported,” said Fath.

He said recently there’s been an influx of people moving in from urban areas because of the pandemic, so maybe newcomers don’t understand Native rights.

In the face of harassment, Jennings remains optimistic. “The fact that we’re still here, still speaking our languages, still harvesting the ways that our ancestors have—we belong to a really strong resilient group of people that know how to adapt, to survive,” said Jennings.

“All we ask for is a little help,” said Greg Johnson. The treaties were signed almost 200 years ago, but “in many ways, we’re still waiting for that peace.”

Banner photo: Tribal members walleye spearfishing in Wisconsin. (Credit: CO Rasmussen/GLIFWC)