Tis’ the season for summer travel — let’s take a look at four U.S. stops steeped in history and lingering pollution.

Summitville gold

The first gold rush in Summitville, Colorado, happened just after the Civil War, when claim jumpers overran a mountainside that belonged by treaty (and history) to the Southern Utes.

A new treaty in 1872 awarded the tribe $25,000 a year in perpetuity for the land. Fast-forward to the 1980’s when “advanced” mining techniques wrung millions more in gold out of the mountain. The advancements involve applying a cyanide solution to rocks to leach out flakes of gold and other metals.

The runoff, already naturally acidic, became downright toxic, with cadmium, lead, and other metals joining the flow.

Summitville became unique even among Superfund sites, even sporting a visitors’ center for the cadmium-curious. The Rio Grande County government, which is in the process of taking over the site with the state of Colorado from the Environmental Protection Agency, has periodically sponsored public tours of the 1,100 acre site. Treating Summitville’s toxic runoff will cost $2 million a year, probably for decades.

Ducktown and Copperhill, Tennessee

If you’re in need of a real-life parable for an Environmental Damage 101 class, few places could beat Ducktown, Copperhill and Tennessee’s Copper Basin. Copper deposits were found there in the 1840’s, and by the Civil War, the basin became an industrial powerhouse for the Confederacy.

Surrounded by miles of hardwood forest in every direction, the Copper Basin was the perfect kitchen for cooking an environmental disaster. The forests became fuel for purifying the copper ore, burning off sulfur in a giant smelter. The sulfur burned into the denuded hillsides, creating an acid rain nightmare made worse by the burning timber. The barren red hills looked like the surface of Mars.

The last mine played out in 1987. The Copper Basin is just recovering today.

Hudson hobbled

New York’s rise to one of the world’s great cities was largely due to one of the world’s great rivers. The Hudson River and its estuary forms one of the world’s great seaports. And in the 18th and 19th Centuries, a great and growing city needed a convenient place to take out its trash and flush its metropolitan toilet: the Hudson was there.

Before its most neglected days, the Hudson was a beautiful example of fecundity – a dirty-sounding word that actually refers to abundance. Writers like Mark Kurlansky have written that Native Americans and early white settlers thrived on wildlife and sea life, like oysters, which had shells nearly a foot long.

But the wildlife dwindled as the human population and its sewage and garbage grew, the Hudson became an eyesore (and, I suppose, a nose-sore).

So appalling were the Hudson and other urban waterways at the end of the 19th Century that Congress passed The Refuse Act in 1899, widely recognized as the nation’s first anti-water pollution law. Subsequent laws tightened the regulatory net, culminating in the Clean Water Act of 1972. President Richard Nixon is widely credited with signing the sweeping legislation. Except that he didn’t.

Nixon is profusely thanked for founding the EPA and NOAA and signing the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Air Act, and more, but he actually vetoed the CWA as too costly. A Congress with bipartisan concern for environmental oversight overrode his veto.

The Hudson has cleaned up relatively well. But nearly the entire riverbed is tainted with carcinogenic PCB’s, dumped for decades by two General Electric factories far upstream. Fines, litigation, and cleanup attempts have failed to cleanse the Hudson. Much of its still-formidable bounty is off limits for human consumption.

A Cold War birthplace

In 1942, the U.S. was scrambling to beat Nazi Germany in developing nuclear weapons. Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves, a fierce engineer, scouted sites for the top-secret Manhattan Project.

Washington State’s High Desert was a prime choice for America’s first plutonium factory. Two small farming towns, White Bluffs and Hanford, were bought out and the Hanford Works rose on 586 square miles along the Columbia River. Three small cities – Pasco, Kennewick and Richland — were built from scratch to serve and house the complex.

Hanford made the plutonium for tens of thousands of U.S. warheads, and beneath the cloak of Cold War secrecy, they made a colossal chemical and radioactive mess that went mostly unnoticed until the 1980’s.

The end of the Cold War made Hanford’s original purpose obsolete, but created a new mission: cleaning itself up. Hanford’s Tri-Cities became the hottest real estate market in the country for a time in the mid-1990’s. Cleanup costs will be in the low billions every year until at least the 2060’s.

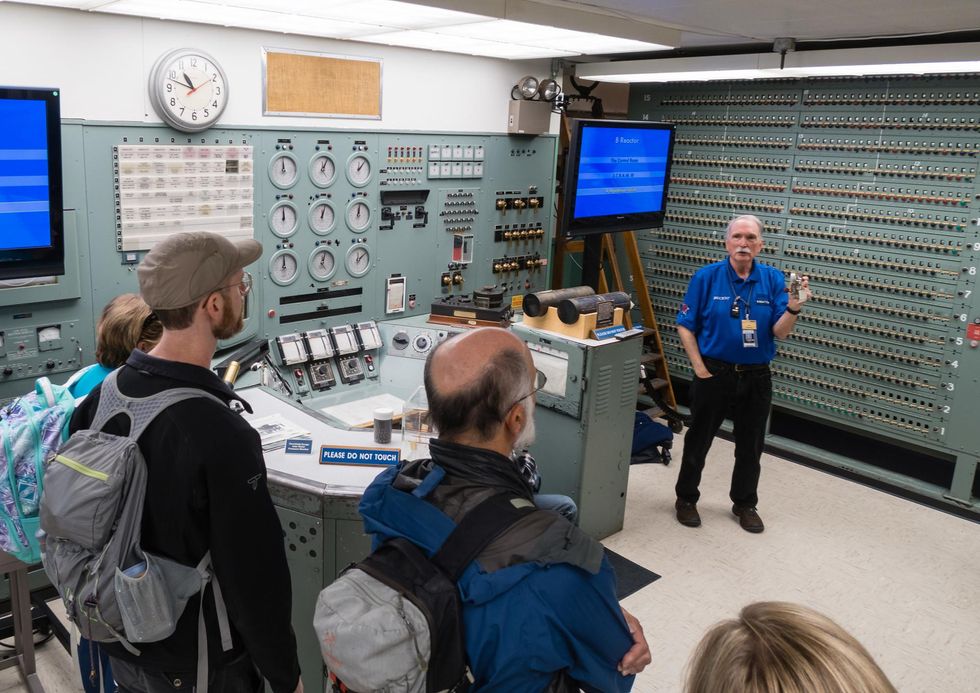

And, pending temporary COVID-19 closures, the former Hanford site will soon re-open for tours as part of the Manhattan Project National Historic Park, administered by the National Park Service.

Enjoy!!

Peter Dykstra is our weekend editor and columnist and can be reached at pdykstra@ehn.org or @pdykstra.

His views do not necessarily represent those of Environmental Health News, The Daily Climate, or publisher, Environmental Health Sciences.

Banner photo: Summitville Mine, Colorado. (Credit: trailscape/flickr)