Tara Dennehy moved to the Pacific Northwest in search of friendlier weather. East Coast summers were too hot, and winters aggravated her arthritis.

Now, she lives in Vancouver, Canada, where winters are more accommodating to her disabilities. This summer, however, nearly sent her to the hospital. Dennehy has autonomic dysfunction, caused by underlying autoimmune conditions. “I can no longer regulate my body temperature much at all. At 85 [degrees Fahrenheit], I can’t do anything except actively fend off heat exhaustion,” she told EHN.

When her apartment reached 95 degrees this June, she “wound up basically having to take a cold bath every two to three hours,” she recalled.

At the same time, Pegasus Jacobs, who shares Dennehy’s condition, felt like they were being cooked alive in their Seattle home. Without air conditioning, they had no way of cooling it down. The nearest cooling center was almost impossible to reach without a car.

“I ended up getting heat stroke and had to call an ambulance,” Jacobs told EHN.

Dennehy and Jacobs are not alone. More than 70 million people currently live with autonomic dysfunction. It’s far from the only medical condition exacerbated by extreme heat—many are common, such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease. Other groups susceptible include those with autoimmune diseases and neurological disorders. Any condition that impairs the body’s ability to lose heat can put someone in danger, Glenn Kenny, director of the Human and Environmental Physiology Research Unit at the University of Ottawa, told EHN. This also applies to medications—many psychiatric drugs can cause increased heat sensitivity.

Heat waves occur when hot air is trapped near the surface for multiple days in a row. Due to climate change they’ve increased in frequency. In the 1960s, the U.S. would have roughly two heat waves per year, but by the 2010s, that increased to six.

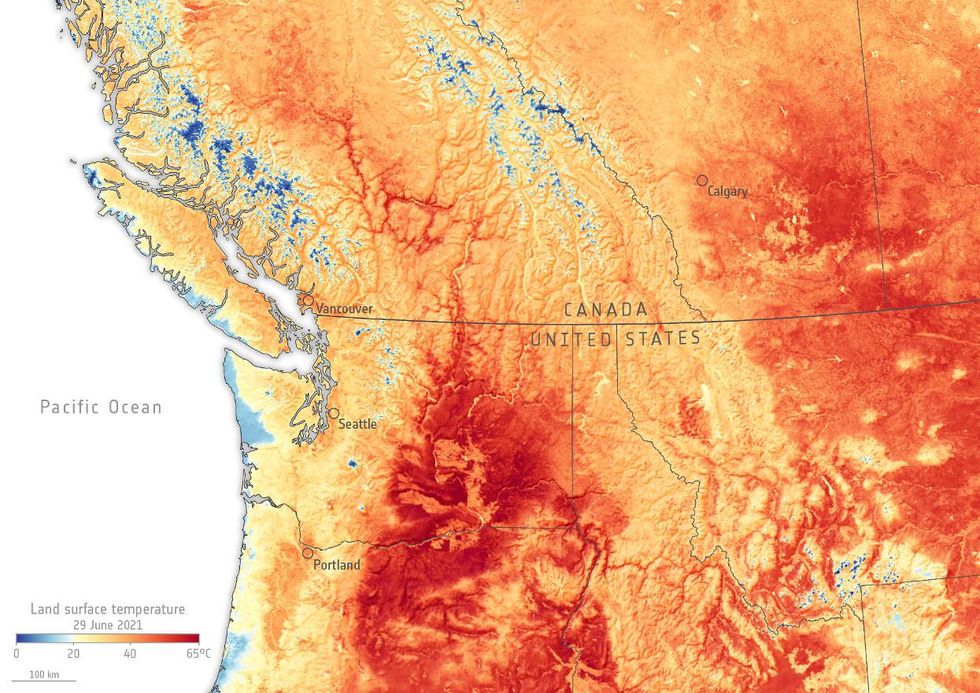

Heat waves are also becoming more intense. For example, the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat dome produced record-breaking temperatures—about 2°C (3.6°F) hotter than they would have been in a world without climate change.

More than 750 heat-related deaths were reported between Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia in late June. There is no official record as to what percentage of these people had chronic conditions. “They don’t usually mark down people with disabilities,” Alex Ghenis, founder of Accessible Climate Strategies, told EHN.

This was confirmed by a spokesperson from the California Department of Public Health, who dealt with their own share of heat waves this year. Similar departments in Washington and Oregon could not be reached for comment.

Despite this lack of data, by looking at other populations that were disproportionately harmed—most have higher rates of disability.

“There’s overlap between age and disability,” said Ghenis. According to a study by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, heat-related deaths amongst adults aged 65 or older are the highest across all age groups.

Heat waves cause disproportionate harm to people living in poverty, communities of color, and homeless individuals. All of these “are bellwether populations for some of the impacts on the disability community,” Ghenis said.

While having a pre-existing health condition can increase the risk of heat-related harm, proper heat mitigation strategies, such as adequate air conditioning and easy access to a cooling center, could prevent these unnecessary deaths.

“It’s more appropriate almost to call [these] manufactured vulnerabilities,” said Ghenis.

Heat stroke and exhaustion

Humans need to maintain an internal temperature of approximately 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit; too large of a deviation can result in dire consequences.

“There’ll be an inflammation-related response and other cellular changes that can compromise [the] overall function” of the body, explained Kenny. If left untreated, this leads to heat stroke and death.

To combat this, we sweat, and our blood vessels expand to transfer heat from our bodies. However, many chronic illnesses and medications impair one or both of these processes. In that case, “they’ll see a more rapid increase in core temperature,” said Kenny.

Heat can also aggravate existing conditions. Ryder Stark, of the Pacific Northwest, has a condition in which their heart struggles to circulate blood throughout their body. The heat makes symptoms worse, causing dizziness and fainting. “When it is hot out, I…have no option but to do all I can to stay cool, or I can become very ill,” they told EHN.

In the case of Jan Groh, of Portland, Oregon, heat triggers her condition, too. She has mast cell activation syndrome, which can cause a severe allergic response to things that are otherwise benign. “I do indeed react to both hot or cold…and this past June’s record-breaking heat wave… drove this home,” she told EHN. “I was sick for three days after it was over.”

There’s also fatigue. “Heat makes everyone slow down a bit,” Charis Hill, a disability activist, told EHN, but explained it can be especially debilitating for people with inflammatory conditions, like Ankylosing Spondylitis.

“On top of the normal drudge of… just like basic living activities, to then add all of the things that I did to…make cooling [myself] easier, it was more than I could do,” they explained.

Access to cooling

During the Pacific Northwest heatwave, Gabrielle Peters, a disabled policy analyst and a volunteer Vancouver City Planning Commissioner, had an information pamphlet entitled “Tips to Beat the Heat” sent to her home.

The first item: “Be Cool. Stay indoors and make use of fans and air conditioners.”

“I have a 10-year-old portable air conditioner that doesn’t really work anymore,” Peters told EHN.

Peters, who lives below the poverty line, couldn’t afford a more powerful AC unit, which “runs anywhere from 75% to 100% of my monthly income,” she said.

When you’re disabled, keeping your home cool isn’t easy.

In 2018, 26% of disabled Americans lived below the poverty line compared to 10% of their non-disabled peers. In Canada in 2017, it ranged between 14% and 28% depending on the severity of the disability, compared to 10% of people without disabilities.

Furthermore, “social assistance programs”—such as Supplemental Security Income in the U.S. and Person with Disabilities Assistance in Canada— “do not allow disabled people to accrue sufficient savings…or to have assets above a certain amount,” explained Dennehy.

This leads to additional compromises, such as lower-quality housing.

“Housing trade-offs are a given,” Laura Lake, of Concord, California, told EHN via email. Referring to her home, she explained, “the poor insulation, old windows…is what made the house affordable to me.”

However, substandard housing drives up cooling costs. Impoverished households spend approximately 8% of their income on cooling, compared to 2% for wealthier populations.

For example, because they live in a home with no insulation, “I have to use the AC more,” said Hill. “My electricity bills skyrocket, like four or five times more expensive than the rest of the year,” despite their medical discount.

“What you should have is not only equal access to air conditioning,” said Ghenis, but also “a policy design of subsidizing air conditioners and AC bills for people with disabilities.”

Cooling centers

For those without AC, there’s another option—cooling centers—but access remains hit or miss.

Several people told EHN that the locations of local cooling centers weren’t well advertised or were too difficult to get to.

“If you didn’t have a car, you had to walk to the bus stop, wait on the bus and then walk to the cooling center,” they said. For someone already sensitive to heat, that wasn’t feasible. They’d also have to pack bags of saline, which they rely on to keep themselves hydrated. Cooling centers don’t have these medical items readily available.

Peters, a wheelchair user with multiple lung conditions, faced a similar situation in Vancouver. “We need to make where [people] are safe, as opposed to telling [them] to bring their oxygen tank and go for a walk in the 37 degree [Celsius] smoke-filled air,” (At the time, Vancouver was plagued with poor air quality due to wildfires.)

“It’s not enough to just open a [cooling] center,” Vance Taylor, Chief of the Office of Access and Functional Needs at the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, told EHN. “We’ve got to be able to inform people about where the center is [and] what resources are available. That’s also got to be done in coordination with transportation providers. If I know where it is, but I can’t get there, it does me no good.”

This past year, the coronavirus pandemic became a factor, as well. “Some cooling centers were closed, such as public libraries or community centers,” Olga Wilhelmi, a project scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, told EHN. “People were hesitant to use those community resources because of the worry about COVID-19.” Disabled people are disproportionately impacted by the virus.

The accessibility of the center itself can also be an issue. “When people go through the door, they’re going to have a wide variety of needs,” said Taylor. For example, “if I need help with…toileting and transferring, that needs to be provided.”

This might include something as simple as having snacks available if someone is diabetic, explained Hill. Or having a counselor available that someone amid a mental crisis can talk to.

For autistic people, “it would really help to have a low-sensory section,” they explained.

Service animal awareness needs to improve, as well, Lake added. “I was afraid I would go there, and they would try and exclude my dog. I have been excluded from, or had to argue about, my service dog in so many situations.”

Power outages

Even in the best scenarios, air conditioning and cooling centers might not be enough as both are subject to electrical outages.

While some cooling centers are equipped with backup power, this is a rarity.

“When it gets hot the demand for electricity increases”, Daniel Kirschen, a professor in the University of Washington’s department of electrical and computer engineering, told EHN. This puts strain on the grid that if left unchecked could lead to a power failure, or blackout.

In order to prevent this, grid operators systematically disconnect people to reduce demand. To most, this is a minor nuisance. But approximately 685,000 people are considered electricity-dependent across the U.S.

For these individuals, their medical devices—which can range from ventilators to dialysis machines—depend on a constant flow of electricity. While most have backup batteries, they’re limited in capacity. Power outages lasting more than a few hours could quickly become a matter of life and death.

“There’s all these cascading effects associated with that loss of power,” said Taylor. “If you rely on power to keep your medicines cool … [or] to operate your lift—either to move you up and down your stairs or to move in and out of bed—all that independence is suddenly gone.”

The number of power failures lasting more than one hour have increased by 60% in the U.S. since 2015—nearly half occur during summer months.

Consulting the disabled community

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), even if we successfully limit global warming to below 2°C above pre-industrial temperatures, deadly heat waves could still become the norm.

However, it is possible to reduce their impact—for everyone— by providing access to air conditioning, cooling centers and higher-quality housing. The first step, however, is to consult the communities most impacted by climate change, including disabled and chronically ill people.

“People in the disability community have so much wisdom and creativity, because our daily existence is navigating a world that…was designed to exclude us,” added Peters. “We have so much insight and awareness of where the [policy] gaps are because we’re living in those gaps. Why wouldn’t you want to hear from us?”

Banner photo credit: Damien Walmsley/flickr