We all have the power to cause change, even if we don’t recognize it.

But sometimes it’s hard to see. Social media inundates us with the visceral impacts of climate change. From the global mega-fires in California that destroyed entire communities, to the devastating flooding in Europe and China this summer, it seems like climate despair is all around us.

But what would happen if, instead of sharing negative environmental news, we began to act? For me, action meant creating HOPE: Humans for the Opposition of Pollution and Emissions, an advocacy group dedicated to advancing scientific literacy and educating farmers in low-income, historically underserved communities. With the advancement of climate change, the burdens of flooding, pollution, and drought can be challenging to manage without external help. HOPE helps communities manage those burdens to ensure food and water security. HOPE fosters togetherness and combats the often-paralyzing realities of climate change.

This essay is also available in Spanish

We’ve been able to work in Western Massachusetts sharing educational material to low-income, underrepresented groups that help convey the importance of action to combat climate change in their community. We host focus groups, webinars, and small group meetings to discuss getting the community “climate-ready.” Through this we have been able to develop climate smart agriculture and strengthen local biota through native gardens.

However, you don’t have to start a new organization to make a difference—it can start with individual habits. Here are some steps that I’ve found helpful to remain positive and action-oriented on environmental issues.

Step 1: Take a digital detox

Psychologists have given our collective sense of doom a name: eco-anxiety. This title suggests that our collective emotional responses to all the despair surrounding climate change are reasonable responses to devastation.

But what happens when we are inundated with eco-anxiety? We see an Instagram video of a patch of ocean on fire, or a report on record-setting temperatures in the Pacific Northwest and a spike in deaths. We turn to Twitter and see a video of Jeff Bezos going to space while we edge deeper into a climate-fueled hunger crisis. And these were examples from July alone!

We don’t often see the hidden good. We need to give attention to those friendly faces on TikTok who teach us how to upcycle clothing, or scientists on YouTube sharing lessons about cleaning lakes and rivers. On Twitter we can follow scientists who know how to reduce global demand for water usage. On YouTube we can learn how to reduce our plastic use.

By detoxing negative messaging out of our digital feeds, we can clear the path in our minds for positive news and interventions. I’ve been curating my social media feeds around creators sharing hope, positivity, and action. On Instagram, this includes folks like soulful_seeds, climateoptimistspodcast, blackinenviron, goodenergy_project, and grounded.hope. I also follow people who I don’t usually see in the climate change discussion: women of color, Indigenous groups, and LGBTQIA+ content creators.

I also concentrate my offline time around fostering physical relationships with people in the community, which helps bring me out of this digital bubble. I can see and understand the lived experiences of my community while also learning about ways people are actively dealing with the climate crisis.

Step 2: Step out of your comfort zone

Change starts with just one person, idea, or action. We can all generate positive change by taking steps outside our comfort zones and challenging ourselves.

During the summer of 2020, I examined data that demonstrated communities with higher populations of minority, low-income, and limited English speaking ability were much more likely to live on or near contaminated soil or water in post-industrialized communities like Lawrence, Massachusetts, and Holyoke, Massachusetts. When I spoke to the community members, they were frustrated that their concerns were not being heard. They shared anecdotes about illness, asthma, and cancer, and they wanted a solution to their growing worries. The news devastated me—but I had power as a community member, as a scientist, and as an advocate for environmental justice to do something.

That is when I began the advocacy group, HOPE. With limited resources, funding, or even support, I recruited people who had the same vision: to have everyone live in a community with clean air, soil, and water, without the concern of environmentally related illness. While we are still in our early stages, we are developing plans to advocate for pollutant remediation in our soil and water. We are also currently working with a grassroots urban agriculture organization called Nuestras Raices, where we are building an urban native garden that will contribute to improved biodiversity and strengthen climate resilience of agriculture. In 2021, we have been working on developing computer simulations that demonstrate how pollutants move in groundwater and how it affects consumer health. All this work is leading up to collaborations with policymakers, district representatives, and companies to help assist in the removal of these pollutants.

This essay is part of “Agents of Change” — see the full series

Starting HOPE was a deep jump outside of my comfort zone. Before I started my PhD in 2019, I had no formal background in environmental science or climate justice. Nearly a year in, when I began HOPE, I realized that anyone can be an agent of change when equipped with knowledge, optimism, and a mission. When I formed the board of directors of HOPE, I recruited people from all different backgrounds: retired schoolteachers, librarians, high school students, local activists, and graduate students. All of the directors felt the same — like this was unfamiliar territory, but once they were comfortable with the science, they felt like could take action.

“Knowing what must be done does away with fear.” This was a quote I thought about a lot in the early days of starting HOPE. There will always be people out there who act as a beacon of hope in our daily lives, our communities, and in our newsfeeds. Take the steps to become a beacon of hope for others.

Step 3: Taking collective action: One idea, one team, one community

In 2018, I worked on a project to address water quality issues in a small Massachusetts town. People there were concerned that after heavy rainstorms, oils and trash were running off from parking lots into the water supply. The fiscal year’s budget was running out, and the river kept failing Environmental Protection Agency water standards.

I was assigned to this project with three white men, all engineers yet all quite different: one was from the football team, one was a self-proclaimed cowboy who drove a tractor to school, and one was an opera singer from Long Island. As the only woman of color, at first it was hard for me to speak up and be a leader. We didn’t know if we could be ourselves in front of each other. Eventually, we bonded over a mutual love of food and laughter. Everyday someone brought in a tasty treat, and someone else would provide lighthearted jokes and news. It took up an extra hour a day, but the community-building and friendship was priceless. I learned that your team starts with you, so build it through kindness and lightheartedness.

Our mutual trust allowed us to pitch ideas that sounded silly. We could be wrong in front of each other because that bond was so well-established.

We were logging 40 hours a week trying to come up with solutions for this town. We needed more people to help, and we thought about asking residents to pitch in. That’s where we got our final idea: to enlist elementary school kids as messengers to tell their parents and everyone they knew about the water problems.

It was kind of like the reduce, reuse, recycle campaign, except our mascot was a cowboy named Runoff Randy and the kids got the title of “Rain Wrangler” if they convinced enough people to volunteer for river cleanup. We avoided the negativity — like how the river was polluted or that the town was running out of money — we focused instead on the importance of hope. We were able to inspire kids of all ages, their families, and other volunteers to work together on a problem that was causing everyone to suffer.

The outcome of this project was a long-term solution for a community in need of a solution to a water quality issue. We were also able to pass on the methodology to other project teams working in other cities in Massachusetts. By the end of this project, I was convinced that with enough hope and trust, everyone can come together as one.

Saving hope

Having hope can seem naïve. But change can spring from hope, and it’s easier than you think. Take the organization I started, for example. Since we began in 2020, we have raised more than $10,000 for water quality and climate research. We have united dozens of people interested in working toward clean air and soil. We have even made plans for a spring upcycling drive, where those who need fashionable clothes can receive them for free, donated from those wishing to upcycle. Most importantly, HOPE stands as an important reminder of the importance of one action and one idea.

Spreading a good idea to reduce the amount of litter in your community could start with just you and your roommate — an initiative that could grow in scale as hope spreads. One idea can spread like wildfire, turning something individual into something communal. Then perhaps even that will gain traction, spreading over social media and through to the world.

Planting seeds of hope can happen through education, research, writing, and even your thinking. Good thoughts can turn into good deeds, which can help reduce pollution and emissions locally, which can grow regionally, and maybe nationally. One small idea can inspire an unlimited number of others.

At the very least, have hope in your ability to be the change.

Cielo Sharkus is a climate justice engineer, NSF scholar, and doctoral candidate at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her work explores the relationship between environmental engineering, climate justice, and public policy. She develops computational models that analyze the socioeconomic and environmental conditions that harm human resiliency in a disaster scenario (i.e., flood or water quality crisis), putting emphasis on socially vulnerable and environmental justice communities. She can be reached on LinkedIn or through her website.

This essay was produced through the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice fellowship. Agents of Change empowers emerging leaders from historically excluded backgrounds in science and academia to reimagine solutions for a just and healthy planet.

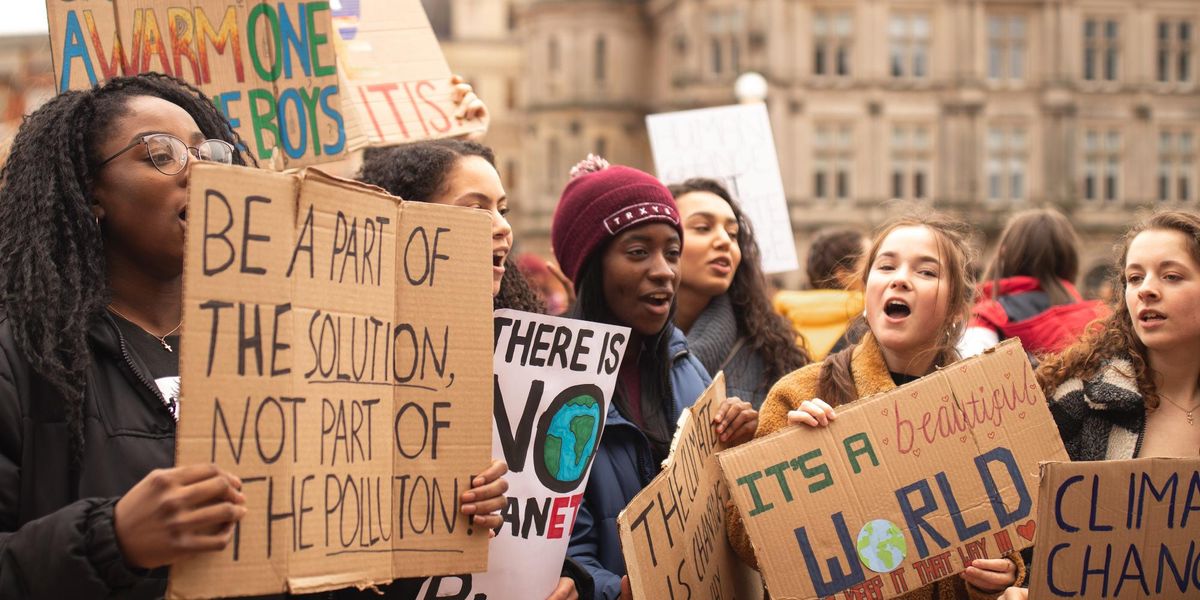

Banner photo: Callum Shaw/Unsplash