The vilification of public health officials in the COVID-19 crisis reminds us of their vital role as the crossing guards of science. When their vigilance gives us the green light to eat, drink, and recreate, we hardly notice them waving us onto normal activities, barely knowing their names.

When the light turns yellow for bacterial beach closures, stay-indoor smog alerts, long-pants advisories for Lyme disease ticks and temporary restaurant closures for rats and roaches, most people accept these measures from health commissioners to assure safety, despite any grumbling over momentary inconvenience.

Even in instances when the light goes red, such as for citywide drinking water contamination, most people are thankful for the guard waving the STOP! sign, even if they have to trudge to the store for bottled water.

The COVID-19 pandemic has put public health officials in a more perilous place—alone in the middle of the intersection, with horns honking in gridlock—caught between the common good and the often-toxic American drive for so-called personal freedom.

Many officials have figuratively been run over in rage by impatient Americans who bolted out of line because they could no longer handle sacrificing their personal desires to save lives.

Threatened health officials

The National Association of County and City Health officials has tallied 28 officials across 14 states who have retired, resigned or been fired during the crisis:

- Nichole Quick quit as the public health officer for Orange County after she and her staff received multiple threats over her order for residents to wear face coverings to help prevent the spread of the virus;

- Emily Brown was fired as the public health director of Rio Grande County in Colorado for resisting the pressure from county commissioners to loosen restrictions. The tensions exploded into a Facebook threat referring to “armed citizens” and “bodies swinging from trees.”

- Amy Acton resigned as Ohio’s state health director amid a backlash over the state’s COVID lockdown that included anti-Semitic slurs and protesters outside her home with guns;

- Chris Dobbins resigned as health director of Gaston County in North Carolina, amid turmoil when the chairman of the county’s board of commissioners pushed hard to reopen businesses against state lockdown orders. Dobbins’ colleagues in North Carolina had named him state health director of the year in 2017.

Many other public health officials are still on the job despite intense harassment. The Colorado Association of Local Public Health Officials told the Associated Press and Kaiser Health News that 80 percent of local health directors reported that they had received personal or property threats and threats to have department funding cut.

Barbara Ferrer, Los Angeles County’s public health director for 10 million people, and Lauri Jones, community health director in Okanogan County in eastern Washington state, which has only 42,000 people, are just two of several public health directors to report having received threats of being shot.

Jones told National Public Radio that, before the pandemic, she was known around the county for being the woman who issued permits for septic tanks, recorded births and investigated reports of food poisoning. She told the Washington Post, “We’ve been doing the same thing in public health on a daily basis forever. But we are now the villains.”

The ones who connect the dots of health

A deeper reason that public health officials are often seen as villains, beyond the momentary culture war over masks, is because they and their departments are also the messengers of data that tells us how healthy or unhealthy our systems are in America, connecting the dots from pollution to housing, from infant mortality to homelessness, from asthma to tobacco and vaping control, and from food deserts to diabetes and obesity.

The understanding of systemic problems has grown to the point that several cities, counties, and states have officially declared racism to be a public health crisis. Undoing such systemic problems will take untold billions of dollars of resources that federal, state and local governments and the private sector have thus far been unwilling to spend.

Among Dobbins’ final acts before resigning was to write a Facebook post saying that his department works to address “all factors that negatively affect health and wellbeing in our community, including racism.”

He said his department recognizes that racism contributes to disparities in “housing, employment, income, incarceration, education and access to services—all of which impact physical, mental and emotional health.” As he added, “racism is an underlying cause of the disparities among those suffering and dying from COVID-19.”

The loss of officials possessing that kind of systemic understanding deeply troubles Oscar Alleyne, the chief of programs and services for the National Association of County and City Health Officials.

An epidemiologist by training and past president of the board of directors for the New York State Public Health Association, Alleyne said the attacks on his colleagues reflect a culmination of several factors. Among them are governmental cuts in public health funding, vigorous attacks on science and scientists by the current administration and vocal anti-science movements on social media, such as opposition to vaccinations.

“Public health not a money-making venture,” Alleyne said. “We really do have an altruistic goal of trying to help people. We look ourselves as society’s safety net. When all else fails, especially for communities that are marginalized, we try to be there for them. The concept that they are being attacked because people need their individuality is perplexing and discouraging.”

Americans get the importance of public health

It is discouraging because actually, most Americans do understand the need for strong public health measures to fight the coronavirus and were willing to put up with weeks of mask orders and closures to offices, schools, churches, sports evets, funerals, graduations and birthday parties.

The number of daily infections, as high as 36,738 on April 24, were mitigated down to a low of 17,618 on May 11. When Sunbelt states began to aggressively reopen their economies in mid-spring, several polls found that up to two-thirds of Americans thought it was too soon to reopen the economy for the many lives it put at risk.

We now tragically see the consequences as the nation hit a new record of 56,567 daily infections on July 3 and now faces the prospect of at least 175,000 deaths by October according to at least two models kept on the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control website. At least 21 states as of Monday have paused reopening plans.

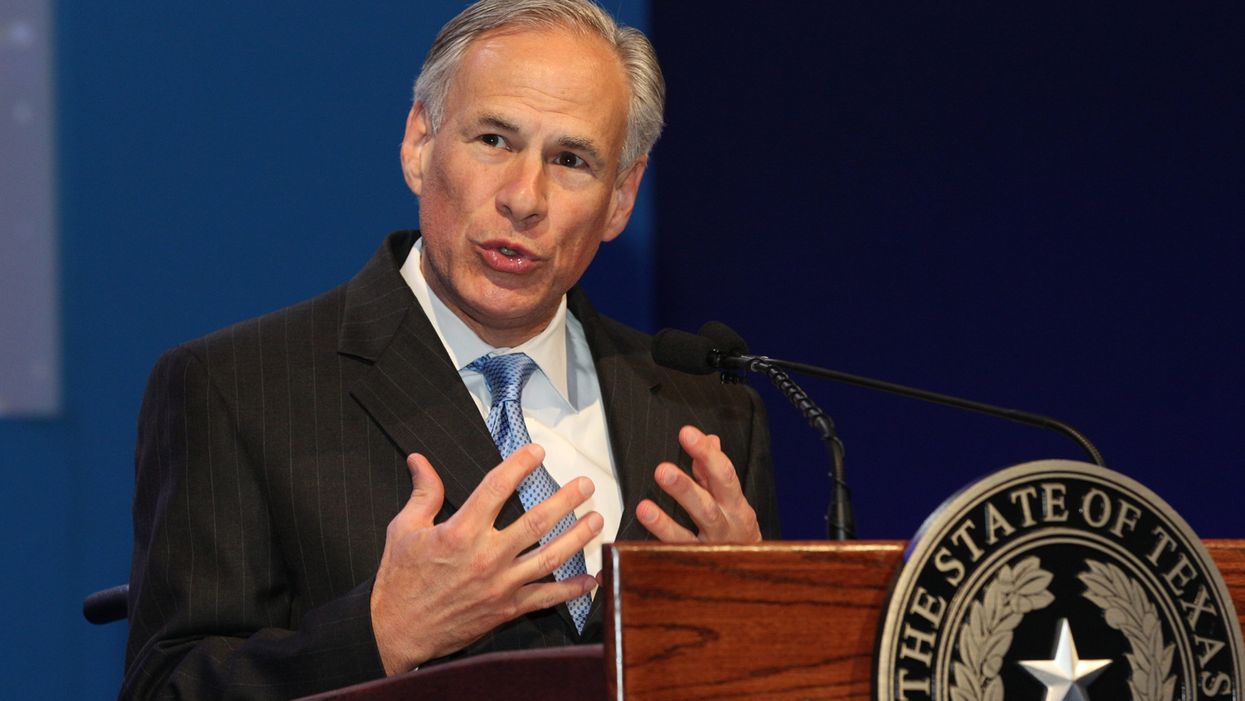

In Texas, despite Governor Greg Abbott’s boasting in June that the state had “abundant” hospital capacity, mayors and health officials in Houston, San Antonio, Austin and Fort Worth say their intensive care facilities are close to being overrun with COVID-19 cases.

Abbott, who, in April banned local jurisdictions in Texas from mandating face coverings, reversed himself last week and issued a statewide mask order. In Florida, where the administration of Governor Ron DeSantis has been accused of firing coronavirus public health data scientist Rebekah Jones for her refusal to manipulate data to justify reopening, the number of daily cases hit 11,458 on July 4—nine times more infections than Florida’s worst day in April.

Meanwhile, the European Union, which was virtually tied with the United States in the spring for also peaking at more than 30,000 daily infections, is now down to 4,000 a day with much stricter and consistent public health measures and political leadership.

As hard as the COVID-19 crisis has been economically and socially, most Americans would have accepted such leadership for tougher measures. Some 72 percent of respondents told Gallup in late June that it is better for people to stay home as much as possible to avoid the virus rather than resume normal lives.

In another late June poll by CNBC, the top three reasons respondents gave for the resurgence of COVID-19 hospitalizations was President Trump, people not wearing masks, and states re-opening too soon.

The question now is whether the instinctive desire of Americans for public health, which goes back to 1799 when Paul Revere was named the nation’s first public health officer in Boston to fight cholera, can win the day without decisive federal and supportive gubernatorial leadership in many states where the virus is now raging.

Confounding this question is the immense amount of backbreaking work that needed to be done to address systemic health and safety inequities, virus or no virus.

Work deferred

“What we do is not new, but our job has grown so much,” Alleyne said. “We deal with all the social determinants of health. We deal with diseases from chemicals—like asthma, from food—like diabetes, from stress of substandard housing and intergenerational poverty. All these things are happening concurrently and determine how long you live.

“To deal with COVID-19, our public health enterprise has had to shift away from opioids, heart disease, children’s health and STDs. I’m worried what happens if these concerns accumulate much longer without our attention. Are we going to see a wave of chronic conditions hit us, with bigger wallop of behavior stemming from social isolation on top of poor health, on top of racism?”

And also, on top of the new vilification of public health officials for being the messengers for masks and lockdowns. In Ohio, Governor Mike DeWine is keeping Amy Acton on board as a senior advisor. On her advice, his state was the first to shut down all schools and delay its presidential primary.

Even though concert promoters and restaurant owners sued her for not advising quicker re-openings, DeWine stood by her as Ohio, the 7th most populous state now ranks 37th in COVID-19 cases per 1,000,000 people and 20th in deaths per 1,000,000 people, according to tracking by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“I will always believe and know that many lives were saved because of her wise advice,” DeWine said of Acton.

Hopefully, the rest of the nation will wake up in time to listen to the wisdom of the rest of our public health officials to save many more lives. Few of us likely remember the names of crossing guards at our schools.

They are the ones who understand the green light of safety, the yellow light of caution and the red light when we must put idle our individual pleasures and privileges so the common good can cross the street.

Derrick Z. Jackson is on the advisory board of Environmental Health Sciences, publisher of Environmental Health News and The Daily Climate. He’s also a Union of Concerned Scientist Fellow in climate and energy. His views do not necessarily represent those of Environmental Health News, The Daily Climate or publisher, Environmental Health Sciences.

This post originally ran on The Union of Concerned Scientists blog and is republished here with permission.

Banner photo: Texas Governor Greg Abbott, who banned local jurisdictions in Texas from mandating face coverings in April, reversed himself last week amid the latest spike in COVID-19 infections to issue a statewide mask order. (Credit: World Travel & Tourism Council/Wikimedia Commons)