“They are playing a game. They are playing at not playing a game. If I show them I see they are, I shall break the rules and they will punish me. I must play their game, of not seeing I see the game.” – R. D. Laing

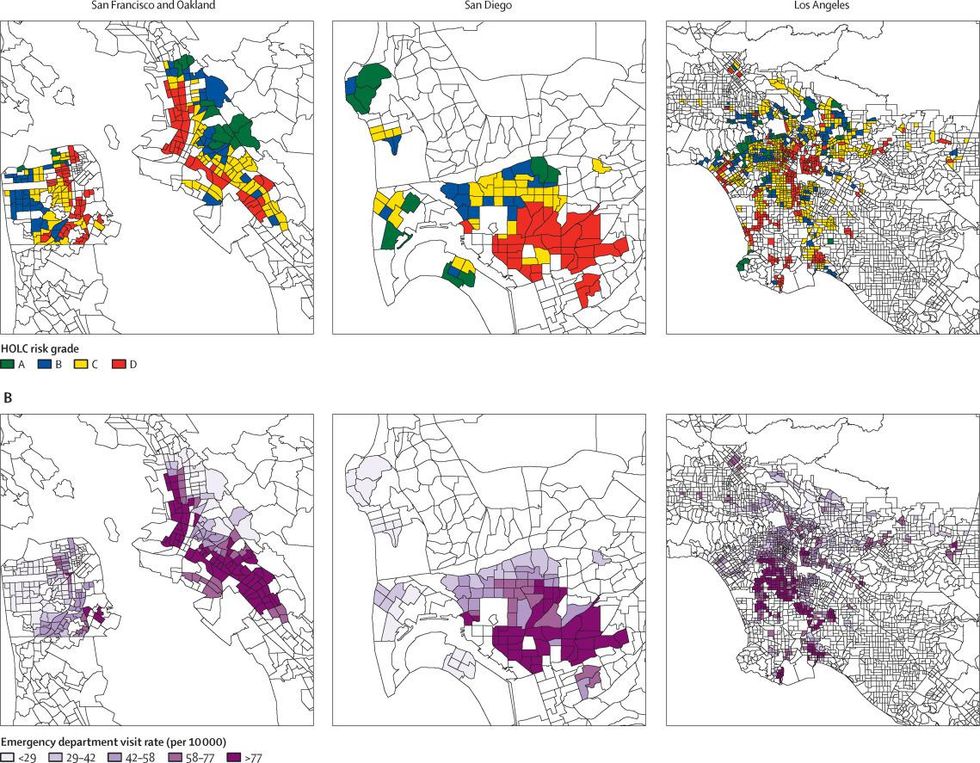

Over the past century, the finance, insurance, and real estate (FIRE) regime has physically and socially engineered inequity. As we barrel deeper into the climate crisis, the same communities exploited by FIRE will face the worst of environmental crises to come and the extreme weather that is already here.

A lesser known part of the story: exploitative FIRE practices not only unjustly concentrated climate disasters in communities of color, but are now barring those same communities from clean energy resources essential for weathering the storm. FIRE’s exclusionary and extractive practices have been folded into the burgeoning clean energy industry, where communities face restrictive barriers to access needed resources for climate resilience. These barriers, such as debt-to-income ratios, upfront capital, and credit score thresholds, intensify inequalities by perpetuating associations between race and financial risk.

How did American FIRE regimes create this terrain of inequality that now dictates an unfair and unjust response to climate change?

FIRE’s racism

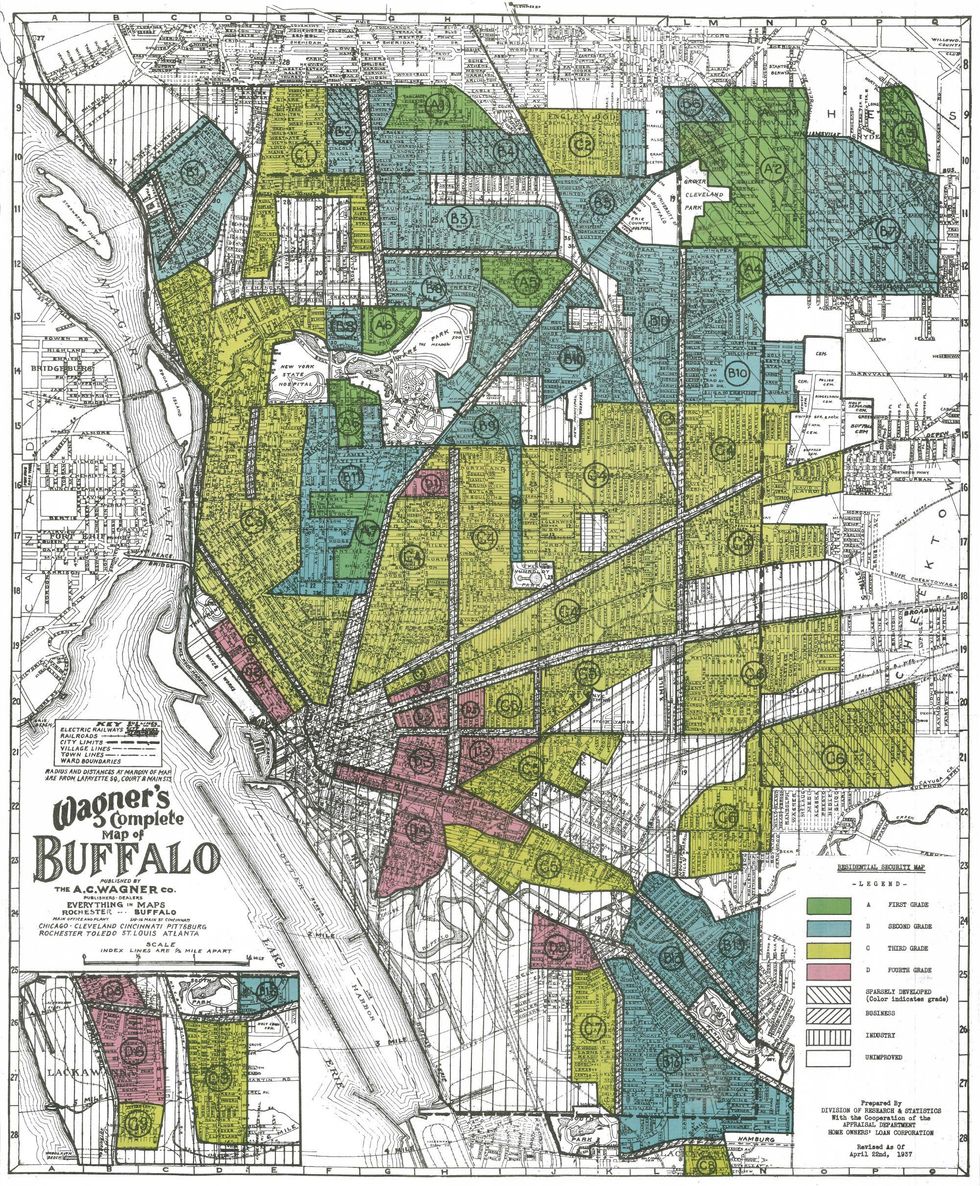

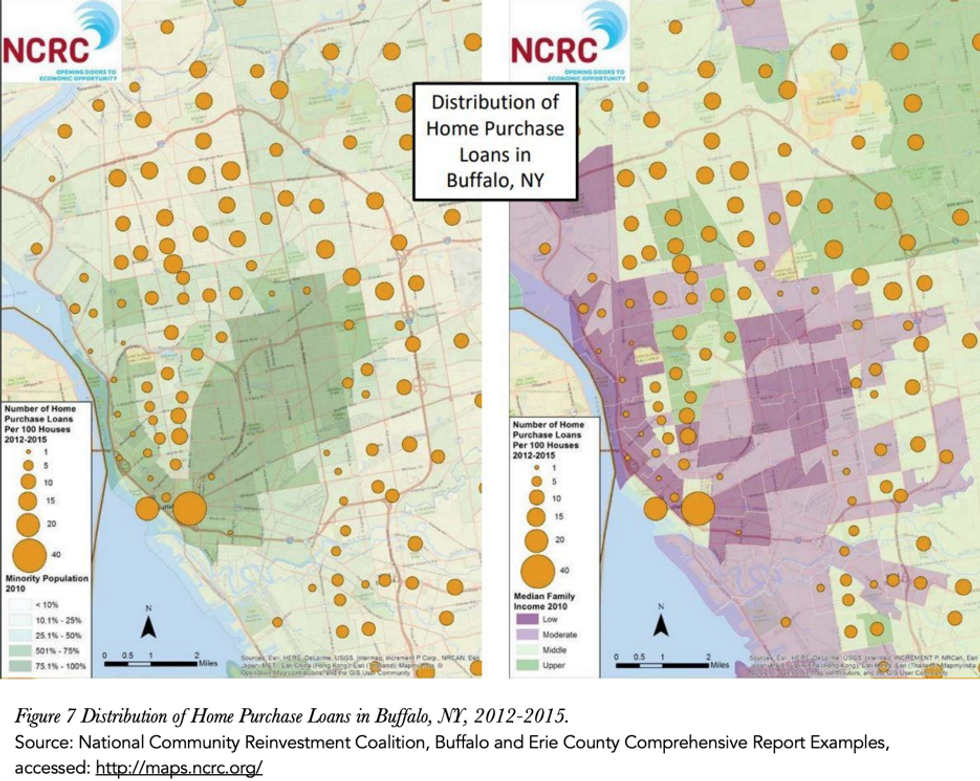

The housing economy is foundational to the creation of the racial wealth gap, given the centrality of homeownership to American wealth building. In the early 20th Century, New Deal era FIRE institutions, particularly the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), created mortgage and lending systems that designated majority non-white neighborhoods as uninvestable financial risks, preventing residents from purchasing homes and building wealth. Known as redlining, this set the stage for even more layers of exclusion.

Without access to wealth creating opportunities, the disrepair and decline of redlined neighborhoods was used to justify Nixonian “benign neglect” and the RAND Corporation’s “planned shrinkage.” These strategies removed essential public resources—such as fire, health, and transit services—from non-white neighborhoods, pressuring residents out and making way for private investment.

Designating entire neighborhoods as financial risks not only paved the way for exclusion from housing markets, they created conditions for extracting wealth. Blockbusting was the real estate practice by which white homeowners were scared into selling their homes at low-cost before their property values would supposedly plummet from an anticipated influx of non-whites. Realtors would then sell those properties, often left in poor physical condition, at an inflated value to people of color through contract selling, where lenders offered loans with unfair terms and inflated interest rates. Homebuyers of color were forced to accept these terms, often left without enough to invest in desperately needed maintenance and repairs. The many unable to buy property became renters, creating another circuit of wealth extraction where landlords could raise rents and overcrowd buildings without incentive to improve the conditions of their properties. Wealth extraction packed people of color into deteriorating buildings without a means for improvements, setting the stage for increased vulnerability to the elements in the decades to come.

Referring to this situation, at a 1966 housing rally in Chicago’s Soldier Field, Martin Luther King Jr. stated, “we are tired of paying more for less.” People of color were prevented from building equity through homeownership, charged more for substandard living because of it, and forced into more debt to pay for it all. Since then, largely thanks to the Civil Rights Movement, the 1968 Fair Housing Act was implemented to put an end to decades of FIRE’s institutionalized racism. However, while outright discrimination was seemingly banned, Black and Brown people today still lag behind in wealth-creating homeownership and carry significantly more debt, while the racial wealth gap has surpassed 1960s levels.

Algorithmic oppression: How FIRE changed while inequities remained

In the last half-century, numerous efforts have been made to outlaw FIRE industry discrimination. Yet companies still determine investment decisions based on calculations that drive racial disparity. Connections between racial inequity and today’s data-driven methods of evaluating “creditworthiness” often go unnoticed because the proprietary algorithms used to determine financial risk are perceived to be “objective.” However, with an understanding of historical context, we see that today’s calculations of investment risk and creditworthiness are in fact reanimations of FIRE’s legacy of racial injustices. While many—but notably, not all—of the FIRE industry’s racist practices were outlawed, generations of exclusion and extraction were not undone, giving way to new forms of racialized financial exploitation under the guise of data.

Take credit scores, for example. Like with intergenerational wealth trends, evidence shows that people also inherit intergenerational economic precarity. While credit scores are not directly inherited, they are nonetheless remarkably consistent across generations. This has compounding effects. As the Debt Collective, a union for debtors and allies, puts it: “The lack of a score—or a low score—can mean higher interest rates within the mainstream banking system. Or it can mean being forced into the arms of check-cashing services and payday lenders.

The worse your score, the more you’re charged—and the more you’re charged, the harder it is to make monthly payments, which means the worse you’re ranked the next time around, putting you on the path to being a revolver, which is of course what lenders want all borrowers to be.”

In other words, the FIRE regime unjustly engineered communities to have low credit and now punish those same communities for their low credit by entrapping them in unfair financial schemes that obliterate credit. This obscene self-fulfilling prophecy must be called out for what it is: racist.

The ongoing legacy of FIRE’s racialized investment regime has manifested a state of disrepair in many communities of color. Neglected and structurally unsound neighborhoods, with aging infrastructure and homes that haven’t been rehabilitated in decades, are disproportionately vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Extreme temperatures, soaring utility bills, floods, pollutant exposure, food insecurity, power outages, storm systems, and epidemics impact low-income communities of color first and worst. To adapt, communities of color are tirelessly advocating for long overdue clean, efficient, and resilient energy resources that continue to remain out of reach because destiny is determined by FIRE’s immoral methods of evaluating financial risk.

Climate redlining

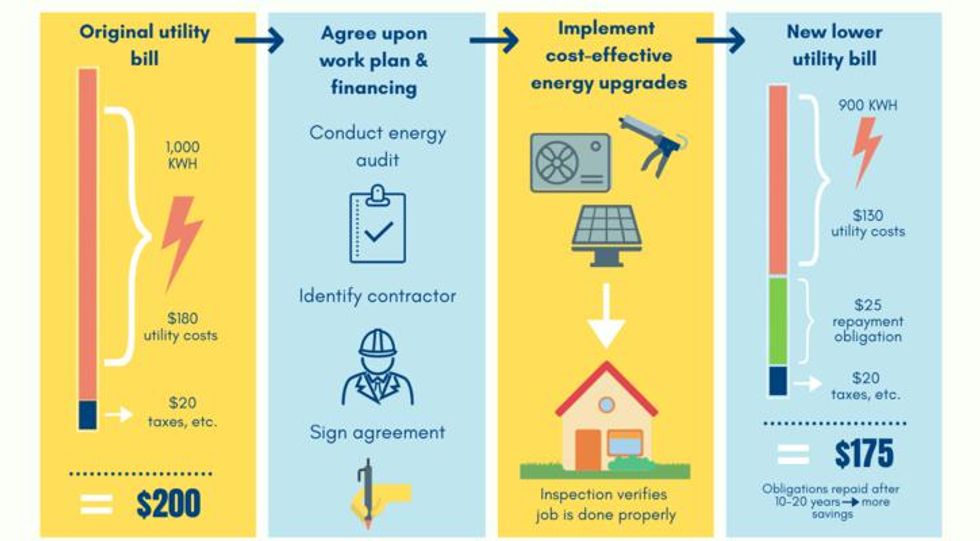

Even transformative and justice-oriented visions for climate action can be consumed by FIRE. In recent memory, Green Jobs Green New York has epitomized this trend. Green Jobs Green New York was envisioned by its grassroots architects as a public clean energy and energy efficiency retrofit program that, in five years, would provide one million housing retrofits and create 60,000 jobs in vulnerable—often formerly redlined—communities. This vision initially demanded that credit scores be cut from eligibility requirements. Moreover, the program would be funded through on-bill financing, a lending program where utility bill savings from efficiency retrofits would pay for the retrofits over a set amount of time. This would mean low-income homes could finally get urgently needed upgrades that had been denied by the FIRE regime for decades, thereby weatherizing climate vulnerable homes while reducing energy usage.

After years of pressuring elected officials, this transformative grassroots vision became official state policy in 2009. The results of the program were abysmal. In 10 years, the program generated fewer than 25,000 retrofits and under 1,700 jobs, mostly in higher-income areas.

A transformative grassroots vision, when made government policy, failed. On-bill financing, while potentially a game changer when done correctly, is still technically a loan program. But what makes on-bill financing unique is that the loan is tied to a housing unit’s energy meter and utility bills, rather than the customer. Yet Green Jobs Green New York was doomed when the New York State government dismissed recommendations to do away with credit score and debt-to-income ratio requirements. The underwriting requirements for the loan were similar to those in traditional FIRE industries, leading to similarly disparate outcomes. Applicants had to show proof of high enough credit scores, low enough debt-to-income ratios, and proof of no bankruptcy. If an applicant didn’t meet credit score thresholds, they could only qualify for a second tier loan based on mortgage payment history, leaving out renters. The grassroots vision to serve the economic and climate adaptation needs of the most vulnerable New Yorkers ended up using tax dollars to help the privileged because government bureaucrats were insistent on fighting climate change with the logics of FIRE.

Moving from extraction to equity in finance

Discriminatory FIRE practices engineered under-resourced and neglected communities, intensifying their climate vulnerabilities, then locked these same communities out of resources needed to withstand the storm. If this trend continues, the inequities that characterized the first four centuries of the American project will continue: those who didn’t create the crisis will face the worst of its wrath in order to benefit a privileged few.

How can we make economic and policy decisions in ways that are mindful of FIRE’s unjust legacy and its creation of an inequitable climate future? When violent histories of racial exploitation are seamlessly cannibalized into obscure three-digit scores, these numbers describe the wealth extraction of lending environments, not the sophistication of borrowers. Methods of investing, lending, and risk assessment must change to prioritize equity. Anything less perpetuates structural violence.

Climate justice is a public good, and equal treatment under the law demands truly collective climate action—a just transition—free of FIRE dogma.

This article was inspired by PUSH Buffalo’s struggle for economic and climate justice in West Buffalo and beyond. The author is indebted to PUSH staff – in particular Andrew Delmonte, Bryana DiFonzo, Rahwa Ghirmatzion, Clarke Gocker, and Michael Heubusch – as well as Orio Amarnath, Adam Meier, Britt Munro, Tok Michelle Oyewole, and Louis Semanchik for their valuable input during the writing process.

Banner photo credit: Fibonacci Blue/flickr

Kartik Amarnath, MS, is the Policy Specialist for PUSH Buffalo and a MD and MPH candidate – currently on a leave – at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University. His writing on energy, environmental health, and climate justice has been published in The Guardian, Naked Capitalism, The Albany Times Union, and academic journals in law and medicine. He can be reached at kkamarnath91@gmail.com.

This essay was produced through the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice fellowship. Agents of Change empowers emerging leaders from historically excluded backgrounds in science and academia to reimagine solutions for a just and healthy planet.