HOPEWELL, Va.—After decades of treating patients with chronic diseases, cardiologist Dr. Cliff Morris realized that to truly make a difference in the community he served, he had to go beyond the doctor’s office.

Dr. Morris works in Hopewell, a small industrial city in central Virginia where the Appomattox and James River meet. A legacy of chemical pollution that includes the biggest chemical spill in U.S. history and a history of racial discrimination have manifested in health disparities such as the nine-year difference in life expectancy between the mostly white western parts of the city and the mostly Black eastern parts (78 years and 69 years, respectively). Furthermore, the city consistently remains at the bottom of Virginia health rankings.

“These are hardworking people, but then their lives are cut short by a heart attack or a stroke,” Dr. Morris told EHN. “Research shows that 90% of American chronic medical problems like high blood pressure, obesity and high cholesterol come from a combination of environment and poor behavior. So how do you affect both the environment and the individual?”

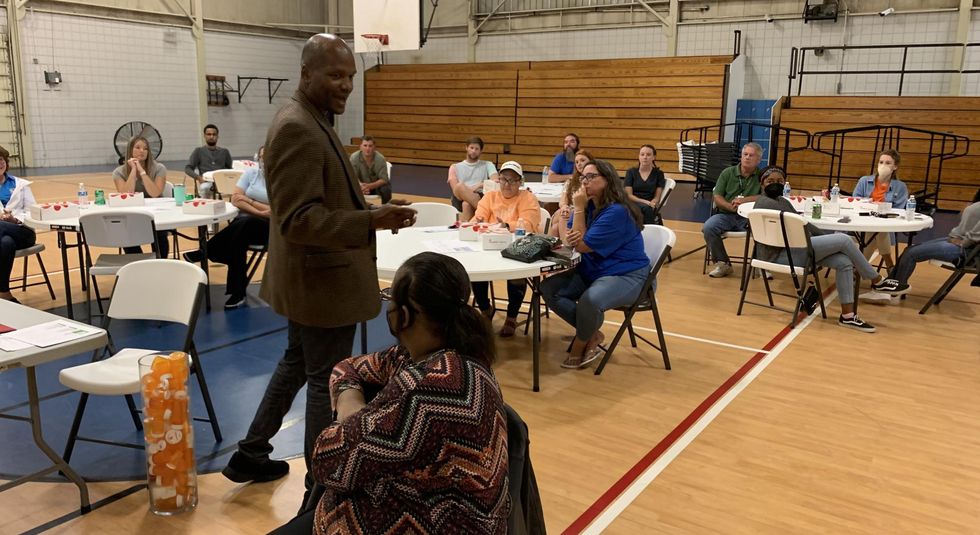

To answer that question, Dr. Morris left his large medical group and opened a small practice to be closer to the community. He sponsored 5K races, taught tai chi, performed fruit and vegetable smoothie demonstrations with local groups and more. However, while these efforts impacted pockets of people, they didn’t improve overall community health. Then he discovered Blue Zones.

Dubbed by National Geographic Fellow Dan Buettner in 2004, Blue Zones refer to five places around the world where people live the longest. The expedition and book has morphed into an organization that works with more than 70 communities in the U.S. to make healthy choices easier for individuals through policy changes to infrastructure and social settings. Blue Zones communities have improved in areas such as food access, economic growth and chronic disease indicators. If Hopewell can secure generous funding and build strong partnerships, the city has potential to create a new legacy of prosperity for all residents.

“I first instituted the Blue Zone principles in my own life. Then I started applying it to my patients and instantly started seeing people coming off their medications, getting happier and getting well,” Dr. Morris said, “to me this seems like an antidote to problems that not only ail Hopewell, but also our country.”

Hopewell is not the only place in the nation facing health disparities and environmental injustice challenges. “When we say environmental racism people think about Hurricane Katrina or Cancer Alley in Louisiana,” Eric Bonds, associate professor of sociology at the University of Mary Washington, told EHN. “However, environmental injustice and racism is all around us.”

What are Blue Zones?

In 2004, five towns across the world became front-page news. Loma Linda, California, in the U.S.; Nicoya, Costa Rica; Sardinia, Italy; Ikaria, Greece and Okinawa, Japan, were named the Earth’s Blue Zones: places where, according Dan Buettner, “people are eating mostly plant based foods, they are moving every 20 minutes or so, they are hugely socially connected, and they are suffused with purpose, not because they’ve tried, it’s because they are a product of their environment.”

The Power 9 principles summarizing the original Blue Zones are based on the findings from two well-regarded studies: the Framingham Heart Study, which linked cardiovascular disease to modifiable risk factors, and the Danish Twin Study, which found only 20% of life expectancy is determined by genes. Alongside cultural and spiritual knowledge from the communities Buettner studied, the Blue Zone argument blends a scientific and holistic approach.

Today, Blue Zones have exploded into a franchise with several initiatives, such as bestselling books and meal planners. One of those initiatives is the Blue Zones Project. The pilot Blue Zones Project was established in 2008 in Albert Lea, Minnesota. Two years later, the town saw a 3.2 year life expectancy increase. Albert Lea also reaped economic benefits such as a 25% property value increase.

Becky Mcdonough, CEO of the Hopewell Chamber, is excited about economic opportunities, such as tourism growth. “I can only imagine people wanting to come here to see how being a Blue Zones community ends up being reflected in the experience if you come here as a visitor,” she said.

If the city is intentional about preventing gentrification, financial gains can help the 25% of Hopewell residents living in poverty better afford healthy choices and provide the city more funds to invest in under-resourced neighborhoods that are overburdened with pollution due to the city’s long history of environmental racism.

Hopewell’s toxic and unjust past

Environmental racism was baked into Hopewell’s fabric since the chemical company Dupont founded the city in 1915. Professor Eric Bonds authored a paper about environmental injustices in Hopewell, explaining that the once proudly self-named “Chemical Capital of the South” intentionally segregated white and Black workers. “[Dupont] had different areas designated for worker housing and there was an area designated for Black workers that was immediately next to the chemical facilities. Then, in the 1940s, the federal government built segregated public housing in the same locations, immediately next to chemical plants,” Bonds told EHN.

Black residents faced economic, political and environmental discrimination in Hopewell. Dupont hired Black residents for the lowest paying jobs. Until a 1983 lawsuit, Black residents were blocked from political participation by illegal voting policies and excluded from important political committees. Furthermore, the Klu Klux Klan (KKK) actively intimidated Black residents, as evinced by events such as robed KKK members confronting Black residents who protested a proposed landfill in 1966, Bonds found. Despite the protest, the landfill was still placed in their neighborhood.

As the years went by, new sources of pollution arrived near Black neighborhoods. In 1975, Hopewell gained national attention for the biggest environmental disaster of the time – the kepone disaster. In 1974, Allied Chemical contracted Life Science Products to produce their toxic insecticide “kepone” in Hopewell. Life Science illegally dumped kepone into the James River, resulting in pollution all the way to the Chesapeake Bay. The plant also poisoned more than a hundred workers who came down with a myriad of symptoms – including dizziness, tremors, headaches, and chest pains – the workers called the “kepone shakes.” When the news broke, the state shut the plant down and placed a 13-year fishing ban on the James River. Allied Chemical settled a federal lawsuit for $13.2 million, which went toward clean-up costs and created the Virginia Environmental Endowment. The disaster catalyzed an exodus from Hopewell for those who could afford to leave and created a stigma that still lingers.

“These powerful chemical companies, city government, state government and the federal government were actively involved in creating environmental injustice in a systematic way over decades,” Bonds told EHN. He wonders, then, what kinds of systematic and intentional efforts are needed to reverse those injustices.

Blue Zones as a potential environmental justice solution

While Blue Zones Projects aren’t known as environmental justice initiatives, Dr. Morris thinks the project has potential to promote it. “For me, environmental justice means the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, nationality, income or zip code,” Dr. Morris told EHN. Blue Zones, he believes, can make healthier choices easier for everyone. “It doesn’t leave anyone out,” he said.

Margaret Brown, senior director of business development at Blue Zones Project by Sharecare, said Blue Zone Projects’ ambition is to “cover the gamut of systems, people and sectors that make a community work to make sure they have representation on the leadership team.”

The Blue Zones Project’s neighborhood-by-neighborhood approach can also address the specific needs of communities impacted by environmental injustice. “Each neighborhood has its own things to overcome in order to come closer to a Blue Zone,” Gerald Napper, secretary of the Hopewell-Colonial Heights NAACP and youth coordinator for the city of Hopewell, told EHN. Napper says one of the biggest challenges in Hopewell is a lack of public transportation to provide residents greater mobility and access to healthy food options.

According to the 2018 Hopewell Comprehensive Plan, the percentage of residents in Hopewell with low income and low food access is about three times higher than Virginia. Dr. Morris envisions improving food access by expanding the Hopewell farmer’s market and having the youth take control over its operation. “The most empowering thing we can do for people affected by health disparities is food,” Dr. Morris told EHN. “Real food that can enhance physical and emotional health and set up opportunities that are just waiting in Hopewell for everyone to become happier and healthier.”

Ryan Ponder, a veteran physical education teacher at Dupont Elementary, hopes to use Blue Zones to address what he describes as “play insecurity”– a lack of safe places for children to play and exercise. “When we look at the map and draw a line to connect all the playgrounds, there is a really big hole in the middle of the city,” Ponder told EHN. He went on to explain that COVID-19 and increasing neighborhood crime has further prevented students, who are mostly low income and of color, from playing outside. Ponder envisions his school becoming a community wellness hub which will include recreational areas and a community garden.

What will it take to make Hopewell a Blue Zone?

To ensure blue zones end up benefiting those who need it the most, Hopewell’s Blue Zone Project would need to include community champions and partner with the private, public and non-profit sectors. In Fort Worth, Texas – the largest U.S. Blue Zone – the project identified target communities through a Well Being index and recruited a diverse group of leaders from each target community to provide advice and feedback. As a result, the Well-Being Index for the most overburdened communities rose 5.4 points.

The Blue Zones Project team plans to take a similar approach in Hopewell. They will work on a four to six month community assessment and identify potential partners and community champions, as well as the strengths, challenges, and opportunities related to health and well-being in the city. The Blue Zones Project team will then present the city with a detailed proposal, and later work with individual volunteers, the city government, and businesses to implement it.

Beyond spurring community engagement, funding is also critical to expand and sustain the initiative. Blue Zones Projects are typically funded by sponsors from different sectors, not from tax-dollars. Hopewell has received a grant from the Cameron Foundation to kick things off, but the overall cost of the project will depend on the solutions chosen. Past projects have ranged anywhere from $3 million to $50 million. “It’s going to be expensive,” said Dr. Morris, “but if we don’t do something it’s going to be tons more expensive. We can’t afford not to do this.”

Community health beyond Blue Zones

The Hopewell Blue Zones Project is part of a larger community health initiative called One Hopewell, which aims to combat health disparities in the city. Unlike Blue Zones, One Hopewell can address issues such as code violations, poor housing conditions, water and air quality, clean drinking water, stormwater flooding, energy burden for low-income residents, and inadequate healthcare access, said former Hopewell Mayor and current city counselor Jasmine Gore. “The goal is to address healthcare comprehensively,” Gore told EHN. “If you do that, we will meet people where they are and lift them up to where the overall citizen base is better.”

Hopewell’s Blue Zones journey is in its beginning stages. It will take five to eight years to establish the project and it can take decades to fully realize results. In the end, Hopewell can hopefully be an example for the nation that while the past may define a community’s present, it does not have to define its future.