PITTSBURGH — Portable air filters in daycares and early learning centers can decrease harmful indoor pollutants by 83%, according to a new report.

The report, published by the Pittsburgh and Philadelphia-based nonprofit advocacy group Women for a Healthy Environment, assessed PM2.5 — fine particulate matter pollution that can penetrate deep in our lungs — at eight daycare centers in Philadelphia that received air filters from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health to help reduce the spread of COVID-19.

Exposure to PM2.5 is linked to health effects including asthma and other respiratory diseases, heart disease, cancer, neurodevelopmental problems like ADHD and autism, and mental illness. Previous studies have indicated that being exposed to PM2.5 during childhood is particularly harmful.

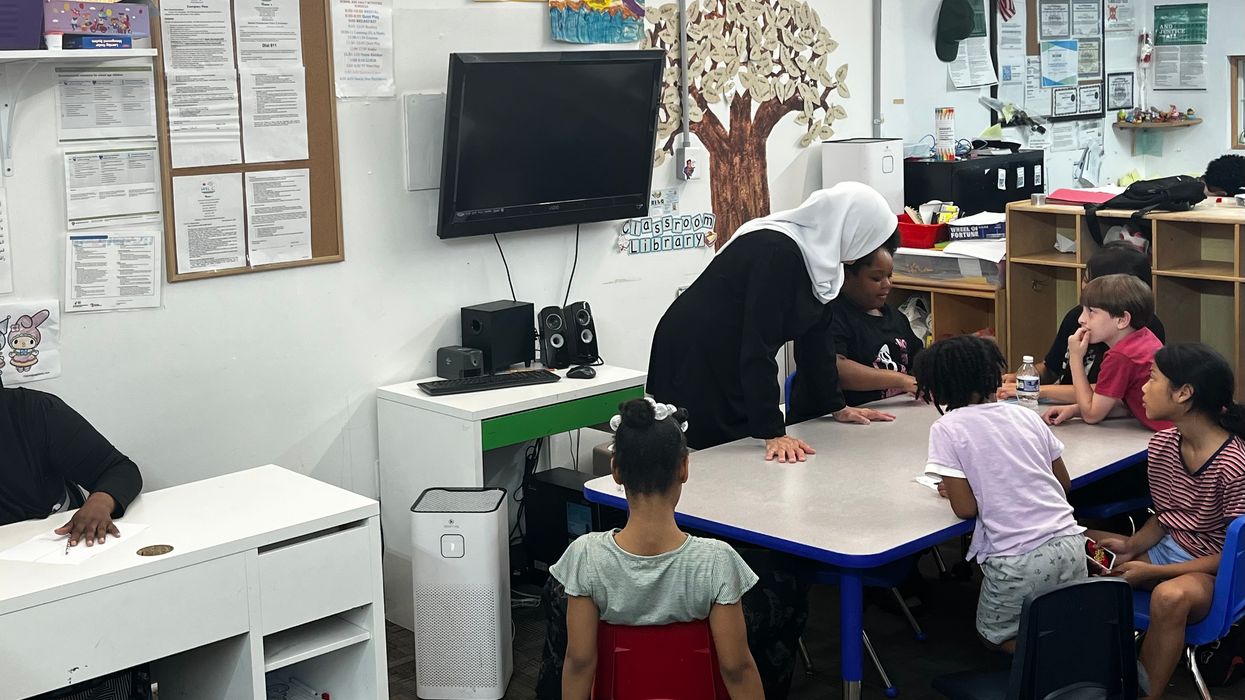

The study was small, but the findings were significant because few studies have assessed indoor air quality and the use of air filters at daycares and early learning centers, where children are particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of indoor air pollution. In addition to the reduced pollution, daycare providers reported multiple benefits including less coughing, allergies and absenteeism.

“You’ve got children as young as 6 weeks old in these spaces,” Michelle Naccarati-Chapkis, executive director of Women for a Healthy Environment, told EHN. “Doing everything we can to protect these littlest ones in the earliest stages of critical development is essential.”

We often think of PM2.5 as an outdoor air pollutant associated with traffic, industrial emissions and burning fossil fuels like coal and oil, but outdoor pollutants that make their way inside can become trapped indoors. There are also indoor sources of PM2.5 like gas stoves, candles and air fresheners, pesticides and cleaning products. The average American spends 90% of their time indoors, so indoor air quality is an important determinant of health.

“Doing everything we can to protect these littlest ones in the earliest stages of critical development is essential.” – Michelle Naccarati-Chapkis, Women for a Healthy Environment

Naccarati-Chapkis said the study’s findings are also relevant to home environments, and that she hopes the findings will inform decisions at the national level and across Pennsylvania.

“People should know that running an air filter at home regularly can make a huge difference in indoor air quality,” Naccarati-Chapkis said. “Now that we know these air filtration systems are so effective at improving indoor air quality, we’d like to work on finding resources to get them into homes and daycare facilities that are situated near major polluters in places like Pittsburgh, where we have more industrial point sources of pollution than in Philadelphia.”

Less illness, better smelling air

The Philadelphia Department of Health distributed the air filters to daycares in four environmental justice neighborhoods, which are typically burdened with higher levels of PM2.5 pollution. They also provided enough replacement filters to run the air filters for approximately three years and ensured providers knew how and when to replace the filters.

“We did a lot of grassroots-level work to deliver these air filters directly to daycares and to help these providers feel empowered to make use of them and understand the benefits so they don’t wind up getting stored in closets,” Tanya Dhingra, pediatric program manager at the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, who led the air filter distribution project, told EHN.

Women for a Healthy Environment reached out about their indoor air study soon after the filters were distributed, Dhingra said, “and it was perfect timing.”

The study used indoor air monitors to measure PM2.5 while the air filters were run on their lowest setting for one week, and then on their highest setting for one week. On average, PM2.5 levels decreased from 6 micrograms per cubic meter to 1 microgram per cubic meter when the filters were run on their highest setting.

“It would have been unethical to ask them to stop running the air filters entirely for the sake of the study, but we likely would have seen an even more significant improvement in PM2.5 if we had,” Lorna Rosenberg, the healthy buildings program manager for Women for a Healthy Environment and leader of the study, told EHN. “Having these air filters on at the highest setting and running continuously when children and staff are in the space is very effective at keeping indoor air clean.”

Some daycare providers reported that coughing, sneezing, allergies and asthma were reduced among both children and the staff, that there was less absenteeism and that daycare centers smelled significantly better during the weeks the filters were running on high, according to Rosenberg. As an unexpected side benefit, Dhingra said, some also reported that the white noise from the filters created a calmer atmosphere and helped some children focus.

More research would be needed to quantify the benefits, but Rosenberg emphasized that we don’t need to wait for those studies to start protecting children.

“People often want to study and study and study some more, but at this point we know that we have effective tools that can help keep children healthier, like these air filters,” Rosenberg said. “At some point we need to stop studying and start giving people the resources they need to protect themselves.”

Women for a Healthy Environment has been sharing their findings with local, state and federal regulators in hopes of seeing the project replicated on a larger scale. Distributing resources like air filters to daycares on a national scale is challenging because each state regulates and certifies daycares and early learning centers differently. In the absence of national programming or regulations related to indoor air quality at daycares, initiatives like this must be done on a state-by-state basis.

“At some point we need to stop studying and start giving people the resources they need to protect themselves.” – Lorna Rosenberg, Women for a Healthy Environment

The Pennsylvania Department of Human Services’ Office of Child Development and Early Learning, which enforces child care regulations, declined to comment on Women for a Healthy Enviornment’s study or answer questions about whether the agency would consider distributing air filters to daycares throughout the state, but Brandon Cwalina, a spokesperson for the agency, told EHN, “facilities are not prevented from installing air filters beyond what regulations outline. DHS is committed to working on solutions that can address environmental health considerations and that further protect children while supporting child care providers.”

A good return on investment

Each air filter cost between $400 and $500, and Dhingra and her team modeled their program after a similar one in Utah that found the average annual cost to run the air filters was $15.81.

“This project really demonstrated how a health department can provide real, tangible resources and help create healthier infrastructure,” Dhingra said. “We think these air filters will provide a sustainable, long term solution for improved indoor air quality.”

Improving indoor air quality is just one of many ways that daycare and early childcare centers can create healthier environments for children in vulnerable stages of development, according to Hester Paul, national director of the Eco-Healthy Child Care program through the national Children’s Environmental Health Network.

“Having quantifiable data like this study can really empower daycare providers to realize that they can make changes and see a meaningful difference in things like indoor air quality,” Hester told EHN. “There are also a lot of free or low-cost things that are easy to do that can make a big difference, including things like using certified green cleaning supplies, switching to fragrance-free products and ensuring good ventilation.”

The Eco-Healthy Child Care program lists 35 low- or no-cost ways that childcare centers can reduce toxic exposures for children in their care and provides endorsements to daycare centers that complete the program. The Children’s Environmental Health Network served as a partner in Women for a Healthy Environment’s air quality study, and Rosenberg helped each of the daycares that participated go through the program and get their endorsement.

“I hope we can elevate this project and this study to the attention of the federal government and create additional resources for reducing harmful indoor air pollution exposures among young children, especially in environmental justice communities,” Hester said.