PITTSBURGH—Air pollution from human-made sources like factories and vehicles is significantly more dangerous to patients with certain lung diseases than other types of air pollution, according to a new study.

Most research on air pollution treats all PM2.5 — air pollution particles smaller than 2.5 microns in diameter (much smaller than a grain of sand) — as equally dangerous.

But PM2.5 can be made up of many components, including things like sulfate, nitrate and ammonium, which primarily come from human-made sources like fossil fuel combustion and industrial emissions, but can also come from natural sources like soil, sea salt and wildfires. This new study is among the first to indicate that the sources of air pollution particles could determine how harmful they are.

“It’s often assumed that all PM2.5 is the same,” Dr. Gillian Goobie, lead author of the study and a doctoral candidate at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Public Health, told EHN. “We now have a better idea of which specific particles are causing the most harm for these patients, and what the likely sources of those particles are.”

The study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, looked at the effects of air pollution from various sources on patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease — a group of more than 200 lung diseases that involve scarring of the lungs. Patients with these diseases are more vulnerable to the effects of air pollution than the general population.

The researchers used satellite data to determine the makeup of PM2.5 pollution and compared the impacts of exposure to different types of PM2.5 particles among 6,683 patients in three groups: one in Canada, one in western Pennsylvania, and one that spans 26 states across the U.S.

All patients exposed to PM2.5 above a certain threshold had worse lung function and were more likely to die than patients exposed to lower levels of air pollution. But the group in western Pennsylvania, who were exposed to similar levels of PM2.5 but a higher proportion of human-made air pollutants than the other groups, had a mortality risk about 6 to10 times as high as the others.

Canadian patients exposed to average annual levels of PM2.5 higher than 8 micrograms per cubic meter had a mortality rate about 45% higher than those exposed to PM2.5 levels below the threshold. Patients in the broad U.S. group exposed to PM2.5 above the same threshold had a mortality rate 71% higher. Meanwhile, western Pennsylvanian patients exposed to pollution levels above the threshold had a mortality rate about 440% higher.

“That magnitude of difference was really surprising,” Goobie said. “Our patients in the western Pennsylvania cohort were almost universally exposed to the highest levels of total PM2.5, and about half of it was made up of primarily human-derived sources, whereas only about a quarter of the PM2.5 the Canadian cohort was exposed to was made up of those sources.”

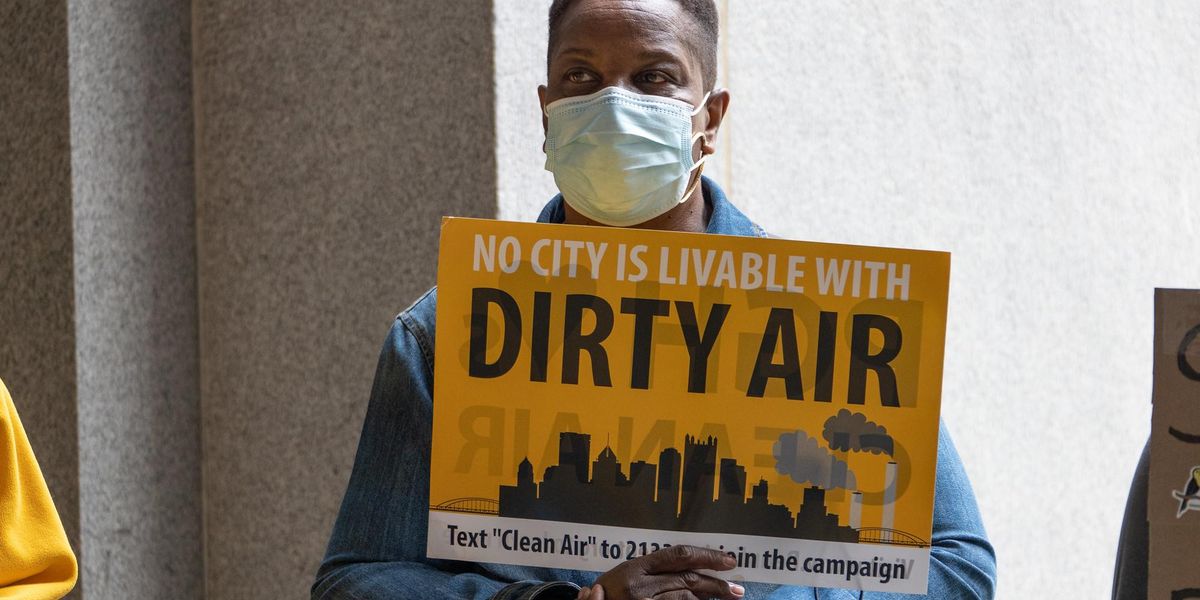

Western Pennsylvania regularly sees some of the dirtiest air in the country, with much of the pollution stemming from industrial sources, in particular from the steel industry.

The researchers broke down the PM2.5 into seven components (along with some additional components that couldn’t be determined):

- Sulfate, which mainly comes from industrial pollution like steel and coal production and fossil fuel combustion (including natural gas and coal)

- Nitrate, which primarily comes from vehicle emissions and fossil fuel combustion

- Ammonium, which primarily comes from agriculture, industrial sources and fossil fuel combustion

- Black carbon, which primarily comes from fossil fuel and biomass burning, including wildfires

- Organic matter

- Ground soil particles

- Sea salt.

“We found that compared to patients in the rest of the U.S. and Canada, patients in western Pennsylvania were exposed to much higher proportions of sulfate, nitrate and ammonium,” Goobie said. “That explains why we see such a different mortality risk attributable to PM2.5.”

While the study focused on those already experiencing lung issues, Goobie said she suspects “that PM2.5 composition is also a critical component of health effects in wider populations.”

“Not all PM2.5 is the same,” she added. “We should emphasize our efforts to reduce emissions from the most harmful sources of these pollutants.”

The researchers used the American Thoracic Society’s recommended threshold of 8 micrograms per cubic meter for annual PM2.5 exposure, which is lower than the Environmental Protection Agency’s, or EPA, legal limit of 12 micrograms per cubic meter. The World Health Organization recommends an even lower annual threshold of 5 micrograms per cubic meter, and has stated that no level of PM2.5 exposure is safe.

The EPA reviews emerging research on air pollutants when considering new federal air pollution regulations. In its most most recent scientific assessment, the agency concluded that the evidence does not indicate that any one source or component is consistently more strongly related to health effects than the size of particles, but an EPA spokesperson told EHN that Goobie’s study “represents an advancement in the science by focusing not on relationships between individual PM2.5 components and health, as has traditionally been the focus of PM2.5 component research, but combinations of components.”

Saving lives by reducing industrial pollution

While treatment can slow progression, there’s no cure for fibrotic interstitial lung diseases. For the most common of the diseases, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the average survival rate is three to five years after diagnosis.

Goobie and her colleagues estimated how many lives could be prolonged if their patients weren’t exposed to PM2.5 levels above the 8 microgram per cubic meter annual threshold.

They found that among western Pennsylvania patients, eliminating exposure to levels of PM2.5 above that threshold could potentially subvert up to 70% of premature deaths. In contrast, eliminating those exposures in the Canadian group would only avoid 5% of premature deaths.

“Policymakers particularly need to be aware of potential risk imposed by industrial sources including the steel and coal industries, and should be advocating for, at a bare minimum, more stringent regulations on industrial polluters,” Goobie said.

In Allegheny County, which encompasses Pittsburgh, annual levels of PM2.5 rarely fall below the EPA’s threshold. The Allegheny County Health Department, which oversees air quality, has increased efforts to improve the region’s air quality in recent years, but declined to comment on the study, saying, “we do not comment or weigh in on the findings of third party reports.”

Patients with lung scarring diseases aren’t the only western Pennsylvanians vulnerable to the effects of air pollution. In Allegheny County alone, there are 25,928 kids and 100,546 adults with asthma, 70,844 people living with COPD, 100,456 people living with cardiovascular disease and 12,752 pregnant people, according to the American Lung Association.

“You can’t just dismiss hundreds of thousands of people who are especially vulnerable to air pollution,” Matt Mehalik, executive director of the Breathe Project, a Pittsburgh-based collaborative of more than 50 regional and national environmental advocacy groups, told EHN. “The standards really should be geared toward protecting the most vulnerable members of our communities.”

New federal air pollution limits

Goobie’s study is timely, Mehalik said, because the EPA is expected to release new proposed federal limits on PM2.5 for public comment any day now.

“That’s the most powerful public health policy tool we have, which could lead to the most health benefits, particularly for those of us living in places like southwestern Pennsylvania,” Mehalik said.

The EPA is supposed to review federal air pollution standards every five years, but the standards currently in place are from 2012 because the agency declined to update them under the Trump administration.

The agency’s recent policy assessment on air pollution focused particularly on health risks to vulnerable populations like those covered in Goobie’s study, the EPA spokesperson said, and the agency is considering those findings while working toward proposing new federal limits on PM2.5 pollution.

It’s unclear what new air pollution limits the EPA could propose, but earlier this year the agency’s scientific advisory committee, a group of researchers and public health officials tasked with reviewing the science and advising the EPA on new regulations, recommended lowering the annual limit on PM2.5 from 12 micrograms per cubic meter to between 8 and 10 micrograms per cubic meter.

“To me, this study provides potent evidence for why these standards need to be lowered as much as possible to protect public health,” Mehalik said.

Environmental injustices

The study also found that in the western Pennsylvania and U.S.-wide patient groups, a higher proportion of non-white patients were exposed to higher levels of PM2.5 than white patients.

In the western Pennsylvania group, 13% of patients with high PM2.5 exposure were non-white, compared with 8% of patients exposed to lower levels of PM2.5. In the broader U.S. group, 14% exposed to high levels of PM2.5 were non-white, compared with 8% of patients exposed to lower levels of the pollutant.

“This indicates that researchers and doctors need to consider the intersectional impacts of pollution and environmental injustice alongside systemic racism and other factors that contribute to disparate exposures and health harms among our patients,” Goobie said.

This finding mirrors national trends: Across the U.S., Americans of color are exposed to higher levels of PM2.5 than white Americans, regardless of region or income level.

The EPA is also paying attention to environmental justice communities in its review of PM2.5. “Sharing the latest [particulate matter] concentration data is part of this effort, helping us give communities — especially those with environmental justice concerns — more complete information about their air quality,” an agency spokesperson added, noting that this information is publicly available through the agency’s Air Trends Report and its environmental justice mapping tool.

“Communities surrounding our most polluting facilities have higher rates of poverty, more people of color, and more people over the age of 65, making them especially vulnerable to the higher rates of pollution they face,” Mehalik said. “We need to invest in the health of these communities so families’ lives are not disrupted by illness and early death.”