This is part 2 of our 5-part series, Pollution’s mental toll: How air, water and climate pollution shape our mental health.

PITTSBURGH—In an average week, NaTisha Washington hears from seniors forced to choose between keeping their water running or paying medical bills, moms afraid to make their baby’s formula with tap water over fear of contamination, and local politicians frustrated by barriers to improving water quality.

“Many of these communities have been struggling to deal with COVID-19 and job loss and all the recent civil rights actions and discrimination issues while also not having access to safe drinking water at home,” Washington, an environmental justice organizer with One PA, a nonprofit community advocacy group, told EHN.

Much of Washington’s work relates to clean water access in low-income western Pennsylvania communities. The problems she sees primarily fall into two categories: Drinking water that’s contaminated with lead and

other toxic chemicals, and the threat of shut-offs due to nonpayment of water bills.

Both of those issues, she said, create mental health impacts like stress and anxiety.

It’s not hard to imagine how fearing that your water is unsafe to drink or will be shut off could contribute to stress, anxiety, or depression. But emerging scientific research also suggests that a common drinking water pollutant—lead—impacts mental health.

Kids are exposed to lead through lead paint, contaminated soil, and contaminated drinking water, which remains

a primary source of lead exposure. No level of lead exposure is safe for children, and blood lead levels lower than those that officially qualify as “poisoning” are still harmful to developing brains.

“We’ve known for a long time that early life lead exposure causes problems related to learning performance and cognitive deficits in children, but now that many lead-exposed [groups of children] have been followed into adulthood, we’re also seeing that later in life they’re more likely to have major depression, schizophrenia, and other psychiatric disorders,”

Tomás R. Guilarte, professor, researcher, and director of the Brain Behavior & the Environment program at the Robert Stempel College of Public Health & Social Work at Florida International University, told EHN.

“There’s no question that even at low levels of exposure there are associations with neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders,” he added.

These findings have major implications in the U.S. and abroad. While bans on lead in paint and gasoline have had a positive impact, roughly one in three children around the world are still exposed to harmful levels of lead. “This is not a trivial problem,” Guilarte said.

In a survey of more than one million kids in the U.S., researchers earlier this year reported that more than half of children have detectable levels of lead in their blood. The exposure was worse for children of color: About 58% of kids from majority Black zip codes and 56% of kids from majority Hispanic zip codes had detectable levels of lead compared to 49% of kids from majority white zip codes.

In addition, about 186 million people in the U.S.—about 56% of the population—drank water from drinking water systems with lead levels above 1 part per billion (the level set by the American Academy of Pediatrics to protect children from lead in school water fountains) from 2018 to 2020, according to a report from the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Western Pennsylvania is particularly at risk:

- The percentage of Pennsylvania children with elevated blood lead levels is more than twice as high as the national rate;

- Blood lead levels in Allegheny County are declining overall, but not equitably: The percentage of children of color with confirmed elevated blood levels is six times greater than the percentage of white children with elevated blood lead levels;

- In 2019, lead was detected in 80% of water systems in Allegheny County;

- Among school districts in 10 Western Pennsylvania counties that tested drinking water for lead in 2019, 71% reported lead contamination, but less than half took action to remove it.

In October, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lowered the threshold for blood lead levels considered “higher than average” from 5 micrograms per deciliter to 3.5 micrograms per deciliter.

This shift will mean that many more children in Allegheny County and across the country will be considered to have blood lead levels requiring intervention. Currently, when a child is found to have a blood lead level higher than the CDC’s previous threshold of 5 micrograms per deciliter in Allegheny County, the Allegheny County Health Department offers a free home investigation to test water, dust, and soil samples for lead.

Chris Togneri, the health department’s public health information officer, told EHN the agency is still reviewing the CDC’s revised threshold to consider updating that policy.

In addition to its lead exposure and drinking water issues, western Pennsylvania also bears a substantial burden of mental illness.

Related: Air pollution can alter our brains in ways that increase mental illness risk

From 2018-2020, 40% of adults in Allegheny County reported having one or more days where their mental health was “not good,” according to state data, a figure that’s higher in Allegheny County than in half of other Pennsylvania counties, and slightly higher than state averages. An estimated 13% of adults in Allegheny County said their mental health was not good for 14 or more days a month.

A survey conducted by the Allegheny County Health Department from 2015-2016 indicates the issue is even more serious among non-white residents: 48% of Black and 47% of Hispanic residents said their mental health was “not good” for one or more days a month, compared to 42% of white residents.

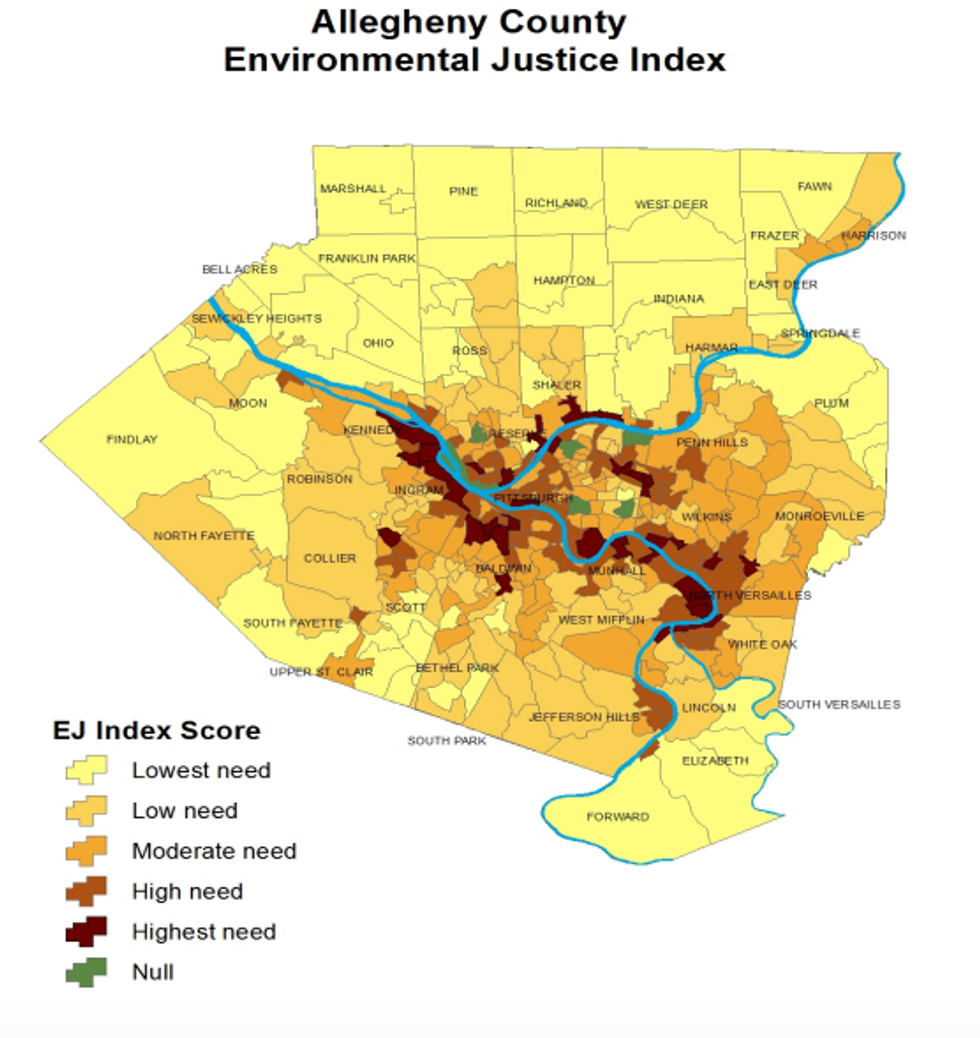

Togneri said the Allegheny County Health Department works to address disparities in lead exposure through an index which ranks census tracts where children are more vulnerable to lead exposures based on factors like race, poverty level, and the age of housing.

“We do increased outreach in the areas that are identified as being at higher risk levels,” he said. “As is the case in all departments, more resources would allow for greater outreach.”

In Pittsburgh, the number of pediatric patients seeking mental health treatment has increased by 30% since the spring of 2020. Meanwhile, Pennsylvania is experiencing a statewide shortage of mental health care workers, and in Pittsburgh therapists are quitting their jobs in droves because of burnout.

This is your brain on lead

Guilarte has been studying lead exposure since the 1980s, when lead poisoning among children was rampant.

He was the lead author on a 2021 literature review that looked at dozens of human and animal studies and found increasing evidence that childhood lead exposure is a risk factor for psychiatric disorders like anxiety, depression, and obsessive compulsive disorders, and neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD, autism, and Tourette syndrome.

The largest of these studies looked at more than 1.5 million people in the U.S. and Europe and found that people who had higher lead exposure as children were more likely to have negative personality traits like lower conscientiousness, lower agreeableness, and higher neuroticism in adulthood (all of which contribute to mental illness).

“Lead exposure impacts a protein receptor in the brain known as the NMDA receptor, which is critically important for brain development, learning, and cognitive function,” Guilarte said, adding that improper functioning of the NMDA receptor is also seen in the brains of people with certain mental illnesses (like schizophrenia). The NMDA receptor influences the development of inhibitory neurons that help keep the brain balanced. When it’s damaged by lead exposure, it creates too few of those neurons.

“In a healthy brain you have excitatory and inhibitory neurons operating in exquisite balance,” Guilarte explained, “but if that’s interrupted and you have too many of one or the other, the brain goes haywire.”

For decades, scientists only considered the impacts these changes had on children’s brains while they were still children, but emerging research suggests some symptoms of the damage done by lead don’t emerge until adulthood or even middle age.

The poisoning of a generation

Aaron Reuben, a researcher at Duke University, led the longest study ever conducted on early life lead exposures and mental health outcomes in adulthood. It followed 579 people in New Zealand from the time they were 3 years old until they were 38 years old, and found that people who were exposed to higher levels of lead as children were more likely to experience symptoms of mental illness as adults, including antisocial behavior, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, substance abuse, delusions, and hallucinations.

“Because we’ve been following these kids for so long we can also look at where they are as adults compared to where their parents were when the study started,” Reuben told EHN. “We’ve found that kids with low levels of lead exposure tend to do a little better than their parents on the whole in terms of socioeconomic standing, but for kids at the higher end of lead exposure, they appear to have slipped down the ladder compared to their parents and have lower social mobility.”

The mean blood lead level for children in the study was 11 micrograms per deciliter. That level is higher than most kids experience today, but it still happens—in Allegheny County at least 582 tests showed blood lead levels higher than 10 micrograms per deciliter in children younger than six between 2016 and 2020, and across the U.S. as many as 243,749 children currently have blood lead levels higher than 10 micrograms per deciliter.

More significantly, that level of lead exposure is representative of the exposures experienced by an entire generation.

“The levels of exposure we looked at are typical for kids born in the 70s in most places in the world when lead was still being widely added to paint and gasoline,” Reuben said. “I’ve estimated that there are about a hundred million people in their forties and early fifties living in America who had high lead exposures as kids.”

Western Pennsylvania has a large population of residents in that age bracket.

In Allegheny, Butler, Washington, and Westmoreland Counties—the four most populated counties in Western Pennsylvania—there are around 371,656 people between the ages of 40 and 54 who likely experienced high levels of lead exposure as children.

In 2016, 18 Pennsylvania cities including Pittsburgh, Altoona, Johnstown, and Erie had higher levels of lead exposure among children than those seen in Flint, Michigan, at the height of its lead crisis.

Additionally, recent reporting on Pittsburgh’s lead crisis revealed that lead levels in the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority’s [PWSA’s] water rose steadily from 1999 to 2016, and that because of inconsistent testing, the region’s water could have had dangerously high levels of lead contamination for years before it was caught during the city’s “lead crisis.” The county didn’t mandate universal blood lead screening for kids until 2018, so it’s difficult to assess just how widespread lead exposure was during that time period.

Even today, despite the county’s universal lead screening program, about 35% of kids in the region aren’t getting tested for lead exposure. In many parts of the country, the percentage of kids getting screened for lead declined sharply last year, likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We don’t have a good understanding of where those children are or why that’s happening,” Michelle Naccrati-Chapkis, executive director of the health advocacy nonprofit Women for a Healthy Environment, told EHN.

The legal federal limit for lead in public water systems is 15 parts per billion (ppb), and PWSA’s lead levels were higher than that from at least 2013-2016. Across the country, about seven million people were served by drinking water systems that exceeded the 15 ppb threshold from 2018 to 2020, according to the NRDC report.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has set a non-enforceable health goal for lead in public drinking water of zero. In 2019 the agency proposed revisions to the Lead and Copper Rule that would lower the action level from 15 ppb to 10 ppb and create stricter requirements for replacing lead service lines, but those revisions haven’t yet been passed.

Overlapping impacts

Across the country, the COVID-19 pandemic has taken a huge toll on mental health. In October, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the national Children’s Hospital Association declared a national emergency in children’s mental health.

“We need more mental health resources and capacity, especially for those in extreme mental health crises,” Marita Garrett, the mayor of Wilkinsburg, a small borough about eight miles from downtown Pittsburgh, told EHN.

Wilkinsburg is one of many communities surrounding Pittsburgh that’s had ongoing problems with childhood lead exposure.

In October, the city of Pittsburgh announced a new lead ordinance that will require testing for lead paint and dust in rental housing built before 1978 (when lead paint was banned), implementing lead safety plans for repairs and demolitions of buildings that could contain lead paint, and installing drinking water filters at city-owned water facilities.

But Allegheny County is home to 130 self-governing municipalities—more than any other county in the state—and the Pittsburgh ordinance won’t apply to them. Many, including Wilkinsburg, have government agencies that are under-funded and under-staffed. Garrett said old lead water lines in Wilkinsburg need to be replaced, but it’s expensive.

Naccrati-Chapkis said Lead Safe Allegheny, a local coalition of government agencies and nonprofits, hopes to help other municipalities in the county use the Pittsburgh lead ordinance as a model to pass their own.

Meanwhile, communities with childhood lead exposures are also likely to experience other issues that can disproportionately impact people’s mental health, including poverty, racism, violence, and other harmful environmental exposures, including air pollution.

Wilkinsburg, for example, is a majority non-white community that experiences high levels of air pollution from U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thomson Mill and has a poverty rate of more than 24%.

In these types of communities, Guilarte said, “It’s almost like the perfect storm for these children to have developmental problems.” He noted that lead poisoning is linked to higher rates of crime and violence, and that mental illness likely plays a role.

Communities with high levels of poverty are more likely to have lead in their water, but research has also shown that regardless of income level, Black children in the U.S. are two to three times as likely as white and Hispanic children to experience lead poisoning—a lingering effect of racist practices like redlining and a clear result of environmental injustice.

“This is a pure consequence of our history of systemic racism and a racialized caste system in America that has still not been adequately addressed today,” Reuben said.

Some of the most high-profile national cases of widespread lead contamination in drinking water have been in majority Black communities, including Flint, Michigan; Newark, New Jersey; East Chicago, Indiana; and Benton Harbor, Michigan, which is unfolding right now.

Examples of “toxic zip codes”—regions where a combination of environmental injustice, poverty, and violence create substantial negative health impacts—abound in western Pennsylvania

For example, the Monongahela Valley (commonly referred to as the “Mon Valley”), a former steel corridor of municipalities from the southern tip of Pittsburgh to the West Virginia border, is home to a large number of environmental justice communities (census tracts with a poverty rate of at least 20% and/or a non-white population of at least 30%) and also faces disproportionate risk of lead exposure.

Duquesne is a Mon Valley town about 10 miles southeast of Pittsburgh that’s about 70% non-white (compared to Allegheny County as a whole, which is 80% white). In June, during one of 10 virtual discussions about the Lead and Copper Rule between representatives from the EPA and cities across the country, Duquesne Mayor Nickole Nesby told the agency that on average, children tested in Duquesne for blood lead levels have an average of 7 micrograms per deciliter.

“Those children are going to need medical services,” Nesby told EHN, pointing to the city’s high poverty rate and noting that 33% of the city’s school children have learning disabilities. At the state level, about 17% of children have learning disabilities. “We don’t even have a medical facility in Duquesne. We need medical care and we need medical research.”

In addition to lead problems, Duquesne’s drinking water contains levels of unregulated contaminants linked to cancer at rates up to 400 times higher than recommended health limits.

Duquesne buys its water from the Municipal Authority of Westmoreland County, but Nesby said contaminants enter the water once it flows through Duquesne’s aging infrastructure, which would cost millions of dollars to repair that the city doesn’t have. Nesby is hoping to use some COVID-relief funds toward that end. She recently traveled to Washington, D.C. to talk about her city’s infrastructure needs before the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

“Our water department is just run amok,” she said. “We need help.”

A 2018 report by the Allegheny County Health Department identified the census tracts in the county with the highest levels of lead exposure risk based on factors like what percentage of homes were built before 1950 (when lead paint and lead water pipes were more common) and what percentage of the population is under 5 years old. Many of those census tracts fall within the Mon Valley.

These overlapping impacts can also have physical effects that impact mental health.

“There’s evidence that one harmful exposure changes the brain in a way that can magnify the effects of another harmful exposure later on,” said Reuben, who has also studied the impacts of air pollution on mental illness. “So it’s not an additive effect—one plus one equals two—but a synergistic effect, where if you’re getting one hit from lead exposure and one from air pollution, they combine to create three or four hits.”

Banner photo: NaTisha Wasington in conversation with Melanie Meade in Clairton, PA. (Credit: Njaimeh Njie)

This story is part of a collaboration between Environmental Health News and The Allegheny Front for a series called “Pollution’s mental toll: How air, water and climate change shape our mental health,” with funds from the Pittsburgh Media Partnership.

Follow the fallout from this investigation on Twitter at the hashtag: #EHNmentalhealth

Struggling with your mental health? Want to take action against pollution and climate change? Check out our solutions guide.