About 2.3 million Americans are exposed to high natural strontium levels in their drinking water, a metal that can harm bone health in children, according to a United States Geological Survey study.

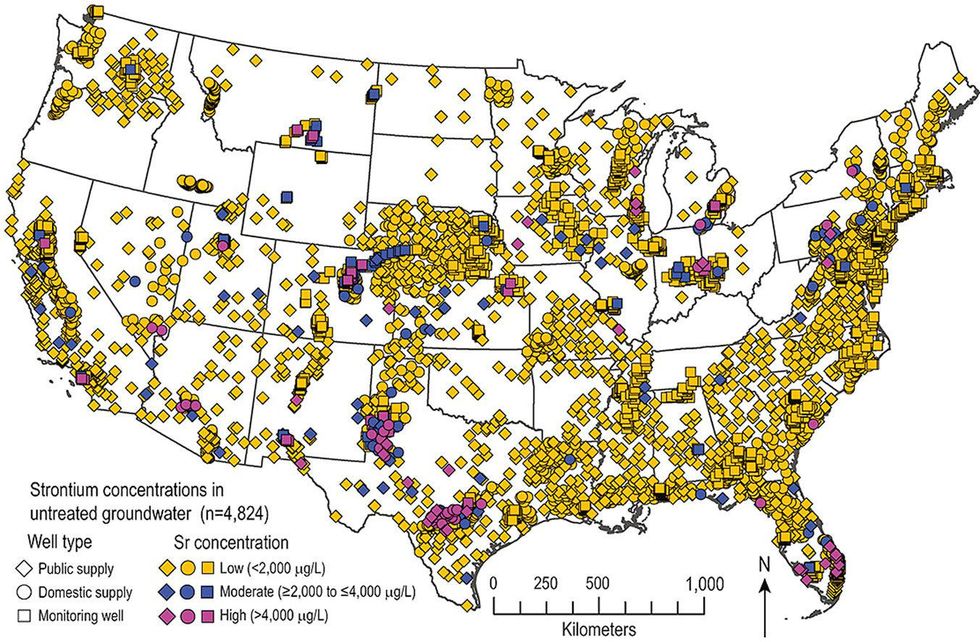

The study, published in Applied Geochemistry, found that almost every groundwater sample across 32 U.S. aquifers had detectable strontium levels, while 2.3 percent exceeded 4 milligrams per liter (mg/L), the maximum amount that people should consume routinely, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. The public and private wells extending from these aquifers provide drinking water for 2.3 million people.

While low amounts of natural strontium are safe and even beneficial for the human body, these high concentrations can stunt bone growth in children who lack adequate calcium intake. Strontium can replace calcium in bones, weakening them and limiting development, according to Sarah Yang, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services’ groundwater toxicologist.

“We’re more worried about infants and children because their bones are actively growing,” Yang told EHN. “Generally infants and children can absorb more strontium in their intestines, and adults can’t.”

High strontium in drinking water is linked to rickets in children, an extremely rare skeletal condition causing soft, sometimes deformed, bones.

Strontium, a soft metal that originates from minerals like celestine, makes its way into drinking water naturally. Aquifers with high strontium concentrations are often surrounded by carbonate rock containing limestone and dolomite.

In the USGS study, author MaryLynn Musgrove, a research physical scientist, found that 86 percent of people exposed to high strontium levels drink water supplied by carbonate rock aquifers. More than half of them are using Florida’s underground reservoirs, where some freshwater has been blending with limestone and dolomite for 26,000 years.

Texas’ carbonate aquifers also stood out.The Edwards-Trinity aquifer system, a sandstone and carbonate formation spanning from Oklahoma to western Texas, had the most frequent occurence of high strontium concentrations in its corresponding wells.

Dolomite is abundant in the bedrock of eastern Wisconsin, where strontium levels are among the highest of U.S. drinking water supplies.

While the USGS study mainly looked at areas exceeding 4 mg/L of strontium in samples, some communities living atop these dolomite layers drink water with more than 25 mg/L, the one-day health advisory limit for children.

“We have a lot of communities that have values above 20, 30, 50 mg/L,” John Luczaj, a professor of geosciences at University of Wisconsin, Green Bay, told EHN.

Removal of strontium from drinking water

While its radioactive sibling, strontium-90, is regulated, natural strontium contamination is unregulated by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The major dilemma, according to Victor Rivera-Diaz, a writer and researcher for Save the Water, is that it is still a “public health mystery.” While some research has conclusively linked strontium to bone degradation, a lack of data has kept the EPA from regulating it under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

“It is a problem,” Rivera-Diaz told EHN. “It definitely requires more attention, even more so in the areas that are prone to high contamination.”

But this is easier said than done, Rivera-Diaz explained.

Strontium cannot be removed with conventional water treatment technology. Thus, communities would have to look to other systems, such as point-of-entry reverse osmosis.

“Some of these technologies can be quite costly, so that might be a barrier for lower-income communities,” Rivera-Diaz said.

Reverse osmosis systems and water softeners are incredibly effective in removing strontium concentrations.

“If it was up to me, I would, in the short term, figure out a way to subsidize technologies that are proven to filter out strontium, especially in those communities where those levels are well above 4 mg/L,” Rivera-Diaz said.

Banner photo: Bluewater Globe/Unsplash