The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted U.S. health inequities—and the field of public health, which includes the branches of epidemiology and environmental health, has long been complicit in sustaining these inequities.

Black and Brown people have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19—and this is not explained by biological determinism, because such theories are racist and false. Centuries of economic, social, and environmental injustice have left communities of color more susceptible to illness and disease.

Knowledge of these health inequities is not new. It is common knowledge within the field of public health that oppressed communities are impacted with a higher burden of diseases. Despite this, it is not common practice for the public health field to address the root causes of health inequities.

As many folks are newly interested in pursuing careers in epidemiology in hopes of addressing these inequities, it is imperative for the world to know that epidemiology has not prioritized uprooting the root causes of health inequities, including the r word: RACISM. Otherwise the field would have begun to adequately name, understand and address the social and political causes sustaining health inequities hundreds of years ago.

However, the field is shifting. Many scholars and communities from oppressed backgrounds are refusing to be erased and silenced and are highlighting the need for public health to take a look in the mirror and dismantle the practices within and outside of the field to achieve optimal health for all, especially the most oppressed.

I am one of those researchers.

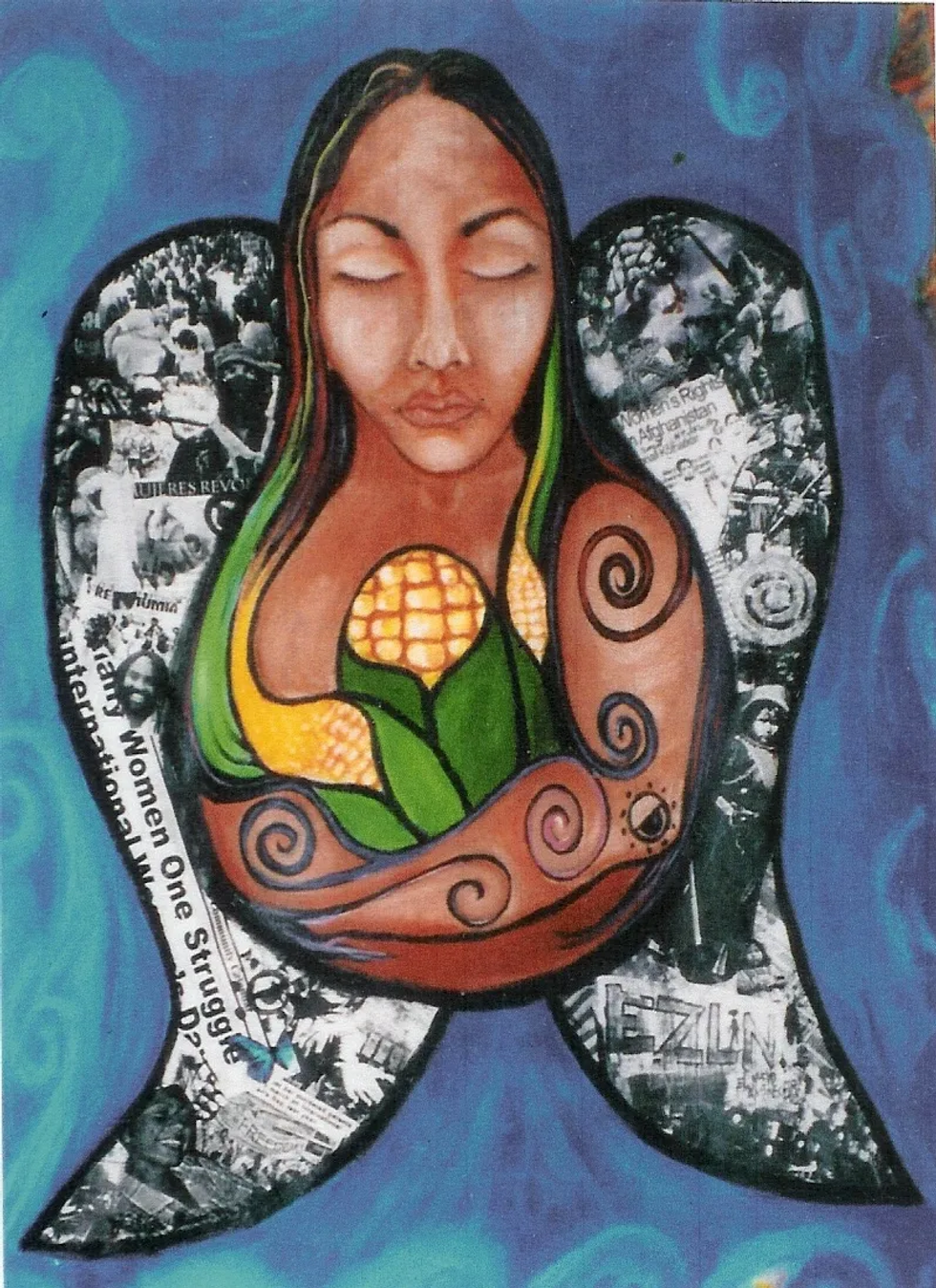

As a Xicana—granddaughter of a Mexican Bracero, with Hñähñu roots—I witnessed systemic barriers to optimal health faced by underserved communities. I came to environmental health because I was raised as a member of a community that thought about how our actions would impact the collective, including nature.

This essay is also available in Spanish

An abundance of family practices connected me to others and the environment. As a young child, my great uncle would solicit my help to desgranar masorcas de maíz para nixtamal de tortilla (shell corn cobs for tortilla nixtamal), passing on the cultural ecological knowledge of Mesoamerica. My parents built a well to collect rain water for home use, connecting me to vital elements.

I also witnessed the exploitation of community members and the environment on both sides of the US-Mexico border. As a child I visited a Mexican community that grieved the loss of their ecology and livelihoods after being displaced by a hydroelectric dam. As a member of a farm worker community, I witnessed exposure to occupational hazards while many farm workers were denied health insurance and basic worker health rights.

I’ve been silenced and witnessed firsthand how the field of public health fails to address oppressive and racist systems. But increasingly I am hopeful—my current department prioritizes equity, openness, learning from failure, and has shown me that advancing health equity is not a fad, but in the words of my mentor, Dr. David Michaels, “it is the right thing to do.”

My MPH cohort was the most diverse —race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality—I have ever been a part of and we lifted each other up. We brought our lived experiences and spoke openly about systems of oppression and health. Environmental Justice wasn’t a buzz word on the backburner, it was at the forefront of our work.

It is through this kind of acknowledgement of racist systems and policies that the field of public health can progress and work better for all communities.

Inspiration from home

I pursued education in global environmental and occupational health to help me better understand how decisions impacting marginalized communities were made without our voices being included.

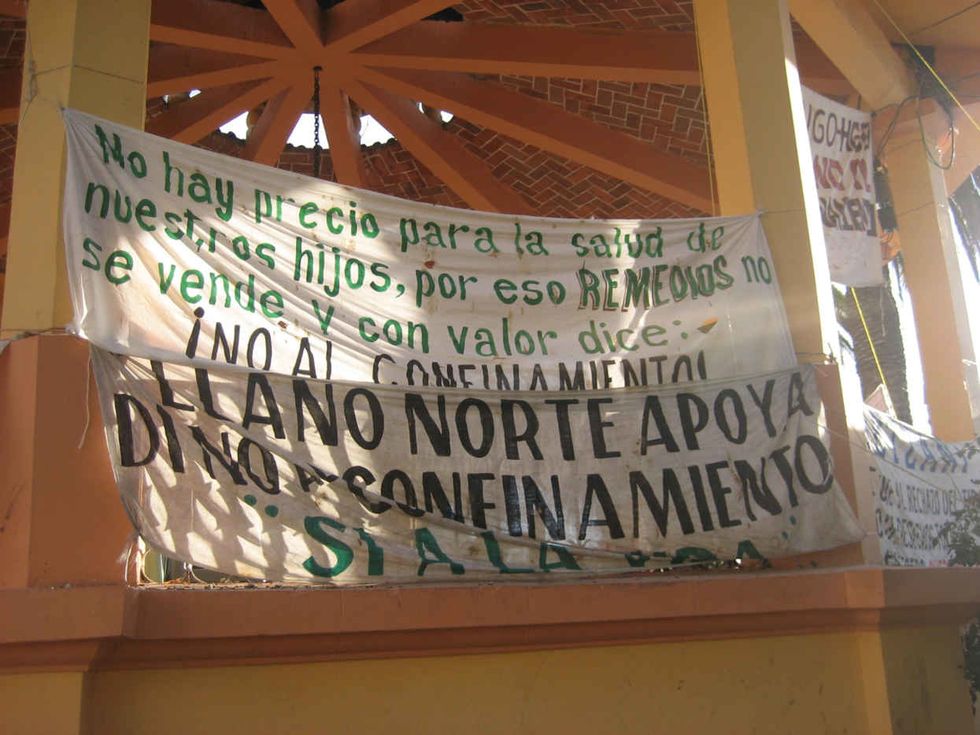

This hit close to home—the community that has been home to my family since pre-Hispanic contact, Zimapán, Hidalgo in Mexico, was being threatened by the construction of a toxic waste site. The decision to house toxic waste from around the world in Zimapán had excluded the community. Additionally, the community was lied to; they had originally been told that a recycling center was being built. But the truth came to light.

This essay is part of “Agents of Change” — see the full series

Recognizing that exposure to such toxics would adversely affect the community’s health and ecology, a local social movement, Todos Somos Zimapán, mobilized to prevent the construction of the site. Community members advocating for a healthy environment were met with oppression and violence, tactics commonly faced by environmental and land defenders around the globe, especially in Latin America.

Zimapán won its fight against the toxic waste site, and it inspired me—catalyzing my academic career and public health engagement; while solidifying my unwavering commitment to social and environmental justice, reverence for nature, and vocational calling to protect the environment and human health.

This career path has helped me identify some of the biggest weaknesses of the public health field including ethnocentrism and lack of understanding systems of oppression.

Reimagining environmentalism

The environmental health field is predominately white and centers on American environmentalism and western scientific values. Western knowledge has monopolized power and presents itself as the one, right way of knowing.

My undergraduate environmental studies program placed John Muir and other racists on a pedestal. Many of my peers signaled their environmentalism through consumption of green products and solo hikes performed while wearing expensive recreational outdoor gear purchased from companies aiming to help American environmentalists “re-create” human relationships with nature, which have been broken.

It goes beyond environmentalism: these views of environmentalism inform environmental health by maintaining white as default and normative. White is most often the race included in environmental health research. The health of non-white people is compared to white people, which neglects the unique experiences, challenges, and characteristics of Black and Brown communities.

Environmental health has also compartmentalized the environment into a series of “exposures” that impact human health. These exposures are framed as separate from humans, and are defined by scientists, not communities.

I’m as American as maíz. Yet, my environmentalism looks different than what was taught in my undergraduate environmental studies program. My environmental health recognizes that environmental justice is reproductive justice is social justice is climate justice is immigrant justice is justice.

My environmentalism is also informed by intersectionality. The environmental health field is barely scratching the surface of understanding race and racism. Intersectionality is a framework that articulates how different systems of oppression, not just racism, intersect and impact the lives of communities and individuals. My environmental health includes understanding how my positionality, including privileges and disadvantages, impacts my engagement with funders, other researchers, and participants.

My environmental health understands that when humans pollute the environment, humans are hurting themselves.

My environmentalism and environmental health echoes that of Berta Cáceres, the Lenca leader who was assassinated in Honduras for defending sacred rivers. In Berta’s Lenca worldview, nature is living and her fight for justice was informed by understanding the intersection of structures of domination and exploitation.

“This mountain region has a strong relationship with the Lenca people, the forests are alive, the mountains are alive. This is a live river that is threatened by the construction of six hydroelectric dams … From the Lenca cosmovision, water is a fundamental element, just like land is part of balance and creation, the spirits live in the water. That is why it is crucial to respect and care for the water as a being just like us. This explains why a community has so much strength to defend a river.” Berta Cáceres (Friends of the Earth 2017)

Speaking truth to power

While I’ve now re-joined a department that acknowledges racism and environmental justice, I learned the hard way that not all institutions do so.

At my former doctoral program, it became clear to me that the department was failing to understand the root causes of health inequities and could improve greatly on their community based participatory research. I felt that a key part of the research should be to better integrate an understanding of root causes of health inequities and anti-racists practices within the department.

I shared these thoughts with concrete suggestions at a meeting focused on the future of the department. I was met by two white female professors saying that I clearly had no idea about community engagement and I must be overlooking the department’s programs conducting community based participatory research for years.

They also repeatedly shut down the voices of the non-white people in the group. Despite this gaslighting, I shared my thoughts to the entire department aloud. The white male leading the meeting met my feedback by stating “okay, we’ll have the department vote on that,” and continued listening to others and incorporating their feedback, but not mine.

There was no vote held, and no discussion about systems of oppression. Disappointed, I left the meeting early. I recognized that the department was not going to change any time soon and I needed to be around people that recognized and named racism.

A few months later, I transferred from the department because I had experienced an unimaginable level of discrimination from faculty, staff and students.

My experience was “disempowering,” to say the least but I share my testimony with other students of color as I encourage them to join or remain in public health field, so that they know that they are not alone when faced with discrimination and tactics to silence their voices or erase their contributions.

As a mentor, I encourage youth of color to pursue public health because we need to be in the positions and rooms making decisions impacting the health of our communities. More often than not, these decisions are made without us.

Prioritizing the health of the most oppressed

One year later, that former department is following the bandwagon of institutions publicly articulating their commitment to becoming anti-racist. My hope is that these words are coupled with actions and that racism is not the only system of oppression that public health condemns.

Sometimes I have felt ashamed of the public health field because it refuses to name racism, sexism, xenophobia, classism and other systems of oppression. I’m inspired by my Agents of Change cohort who unapologetically fiercely bring to light the many ways that environmental health can improve. Their work is infused with abundant tangible ways to dismantle systems of oppression and move towards health equity.

I have some suggestions of my own for the field:

- Name racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, classism, and work towards dismantling these oppressive systems.

- Know what policies and histories have sustained these systems of oppression.

- Teach students, staff, and professors to identify how they benefit and/or are disadvantaged because of these systems, and how that plays out in their research funding, participant relationships, opportunities, and elsewhere. This is called understanding your positionality.

- Stop biting the hands that feed and heal us (farmworkers, health care workers and other essential workers).

In my research I hope to instill these ideas and continue to speak up in the face of injustice, because the lives of oppressed and marginalized communities are literally at risk, mine included.

I extend an invitation to all to prioritize the health of the most oppressed, because our liberation is tied to each other. There are strings attached, and COVID-19 clearly demonstrates this. We must be committed to each other.

Brenda Trejo, MPH is a PhD Student in the Environmental and Occupational Health Department at The George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health.

This essay is part of “Agents of Change,” an ongoing series featuring the stories, analyses and perspectives of next generation environmental health leaders who come from historically under-represented backgrounds in science and academia. Essays in the series reflect the views of the authors and not that of EHN.org or The George Washington University.

Banner photo: Jorge Garza — http://www.qetza.com/