US government health agencies need to move quickly to launch broad testing of people exposed to types of toxic chemicals known as PFAS to help evaluate and treat people who may suffer PFAS-related health problems, according to a report issued today.

The report recommends that the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention advise clinicians to offer PFAS blood testing to their patients who are likely to have a history of elevated exposure to the toxins. Those test results should be reported to state public health authorities to improve PFAS exposure surveillance, according to the report, issued by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or NASEM.

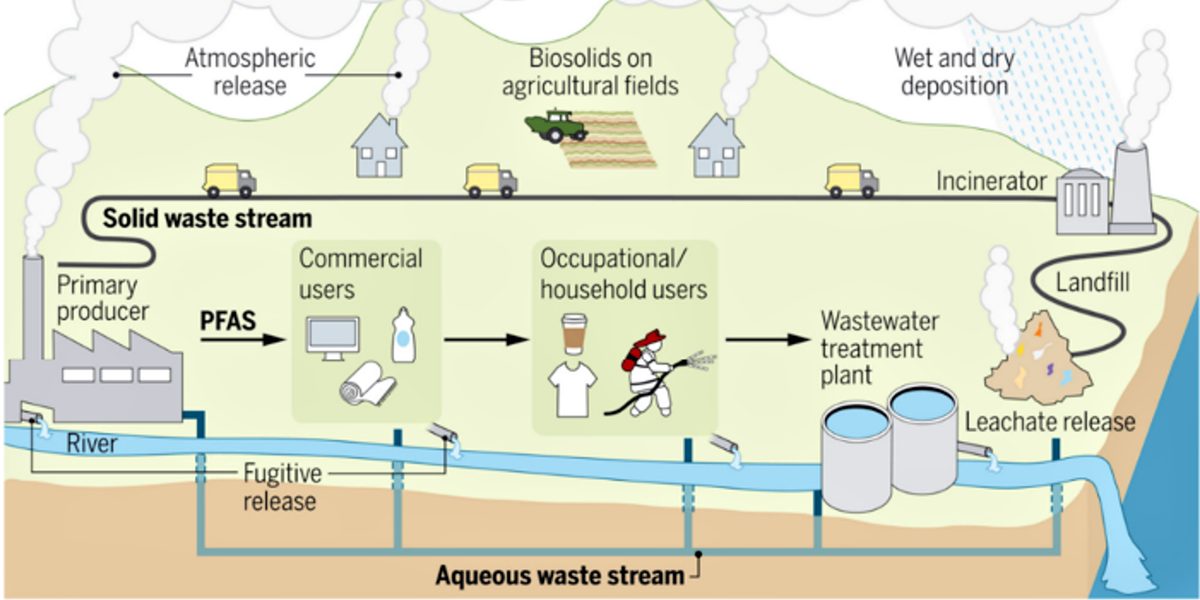

The testing should be done for people with occupational exposure, as well as those who have lived in communities with documented contamination, and those who have lived where contamination may have occurred — such as near commercial airports, military bases, wastewater treatment plants, farms where sewage sludge may have been used, or landfills or incinerators that have received waste containing PFAS, according to the report.

“Our report shows that we are going to need robust and effective collaboration between local communities, states, and federal agencies in order to respond to the challenge of PFAS exposure,” Ned Calonge, chair of the NASEM committee that authored the report, said in a statement.

‘Make PFAS testing available’

“We need to continue to identify communities with elevated PFAS exposure, learn more about specific health impacts, make testing available to patients, and give clinicians more strategies for counseling patients and providing preventive medical care,” Calonge added in the press statement. Calonge is associate professor of family medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver and associate professor of epidemiology at the Colorado School of Public Health.

NASEM acts as the collective scientific national academy of the United States and its recommendations typically are highly regarded. It was created to provide independent and objective guidance that informs American policy.

The report released today is sponsored by US Department of Health and Human Services.

PFAS, the ‘forever chemical’

PFAS is an acronym for a class of chemicals known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. PFAS are also often referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not break down in the environment and bioaccumulate, persisting in the bodies of humans and animals. There are more than 4,000 man-made PFAS compounds used by a variety of industries for such things as electronics manufacturing, oil recovery, paints, fire-fighting foams, cleaning products and non-stick cookware.

People can be exposed through contaminated drinking water, food and air, as well as contact with commercial products made with PFAS. Some PFAS have been linked to cancer, immune deficiencies, thyroid disease, and other health problems.

How PFAS enters the environment

Last year, the US Environmental Protection Agency identified more than 120,000 locations around the United States where the agency believed people may be exposed types of PFAS. The scope of the list underscored that virtually no part of America appears free from the potential risk of air and water contamination with PFAS.

The Biden Administration has announced a series of steps to try to restrict PFAS from contaminating water, air, land, and food as well as to clean up PFAS pollution and speed up research on other PFAS issues.

Last month, the administration started the process of designating two types of PFAS – PFOA and PFOS – as hazardous substances under the law, which would allow the EPA to deploy recover clean-up costs from companies responsible for contamination and take other steps to address contamination.

NASEM said a large body of scientific literature on PFAS shows there is “sufficient evidence” of association between exposure to PFAS and increased risk of decreased antibody response in adults and children, abnormally high cholesterol in adults and children, decreased infant and fetal growth, and kidney cancer in adults.

The report found there was “limited or suggestive evidence” of increased risk of breast cancer in adults, liver enzyme alterations in adults and children, pregnancy-induced hypertension, increased risk of testicular cancer in adults, thyroid disease and dysfunction in adults, and increased risk of ulcerative colitis in adults.

The NASEM report warned that people with PFAS in their blood above 2 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL) but below 20 ng/ml may face the potential for adverse effects, especially “sensitive populations,” such as pregnant women. Clinicians should encourage reduction of PFAS exposure for these patients and prioritize screening for a range of health problems that include hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, breast cancer, signs of kidney and testicular cancer and of ulcerative colitis, according to NASEM.

People found with PFAS in their blood at levels higher than 20 ng/ml potentially face a higher risk, the report states.

The report noted that more information is needed on how PFAS affects children and pregnant women, and recommends the gathering of data to address those groups.

Environmental justice and systemic racism

The report notes that systemic racism and issues of environmental justice could compound the “challenge of responding clinically” to PFAS contamination.

The report notes: “While environmental justice research specific to PFAS contaminants has been limited, place-based factors that may put individuals at greater risk of exposure (siting of chemical companies, refineries, and industrial sites), coupled with insufficient access to environmental screening, information, and adequate health care, have disproportionate impacts on Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous communities, as well as low-income populations.”

“PFAS contamination did not just randomly occur in rural communities serviced by well water that happened to be near industrial sites. Rather, the locating of certain industrial sites and decisions to dispose of PFAS with limited regard for the surrounding community’s access to safe water are rooted in the relationship and history of these industries and communities.

The disposal of these chemicals did not occur as single events lacking context, but reflected a pattern of decisions made over time. Understanding the historical and social context influencing how and where PFAS are distributed is an essential part of identifying effective mitigation strategies.”

This story was originally published in The New Lede, a journalism project of the Environmental Working Group, and is republished here with permission.