In addition to great concern over the COVID-19 pandemic, I’m also disappointed.

For more than half a century, scientists have been expressing concern over the deterioration of what I like to call the “epidemiological environment.” That environment consists of the constellation of circumstances that influence patterns of disease and factors related to health.

It includes such things as population sizes and densities, diets, speed and type of transportation systems, toxics, climate disruption, frequency of human-animal contacts, availability of medical isolation facilities, stockpiles of medicines, vaccines, and medical equipment.

The epidemiological environment also includes cultural norms: levels of education, equity in societies, competence of leadership. Few aspects of the human predicament do not impinge on our epidemiological environment.

My own interest in one part of that environment, transmissible diseases, started as a grad student working on the evolution of DDT resistance in fruit flies. The results of that research had obvious implications for the evolution of antibiotic resistance, a key element in the epidemiological environment.

It clearly influenced my wife Anne and my scenarios in our 1968 book, The Population Bomb and a section on the epidemiological environment in The Population Explosion, the 1990 sequel book. We were responding not just to our own fears, but the fears of colleagues much more knowledgeable in areas like virology and epidemiology.

Of course, the utter failure of global society to deal appropriately with high probability threats to civilization warned of by the scientific community is hardly limited to pandemics.

Climate disruption is the best recognized of contemporary health threats, but the decay of biodiversity, and “updating” the American nuclear triad as part of the Russian-United States’ “mutually assured imbecility” are among the most critical.

Those, at least, are not obvious to the average citizen or decision-maker, but what about others such as increased flows of plastics and toxics (especially synthetic hormone mimicking compounds) into the global environment?

Everyone knows about volumes of plastics in waste streams and oceans and has personal experience with the thermal paper receipts coated with bisphenol-A (BPA), yet little to no remedies have been undertaken.

Indeed, why are there so few effective responses to the epidemics and the maladies of industrial civilization?

Bolster basic medical care

It is convenient for progressives to blame the COVID-19 disaster in the United States on the spectacular incompetence and corruption of the current Republican national leadership. Yes, it has turned away from science, and worked hard to speed the demise of civilization.

One of the Republicans’ many steps in that direction was to destroy the global health security and biodefense directorate that the Obama Administration created to help prepare for emergent diseases. Americans are now likely paying with their lives for Trump’s move there.

But the basic problem dates much further back and is bipartisan. After all both parties have been supportive and remain supportive of the growthmania that has been the basic driver of environmental destruction.

Rather than dwell on the past, however, let’s look at what the U.S. should be doing about the epidemiological environment starting right now. The U.S. has long stood alone in failing to supply all its citizens with health care, an error COVID-19 has highlighted. Changing that, however it is done, should be top priority.

Besides the obvious ethics and justice reasons, people without basic medical care exacerbate public health problems, especially pandemics, in ways that threaten even senators and presidents.

A comprehensive national health program should also remove incentives for infected people to go to work sick and for keeping businesses and other entities that provide essential services functioning.

Plans and equipment should be put in place to greatly increase the capacity of the medical system to deal with large surges of victims of epidemics.

Programs are needed to keep both the plans and essential supplies up to date. A provision for quickly establishing unified leadership in disasters is essential.

Climate change and biodiversity

U.S. security in a globalized world demands leadership in dealing with all aspects of the world’s epidemiological environment.

In addition to rejoining the Paris agreement, America should demand greatly increased ambition in replacing fossil fuels in energy systems so it will have a better chance of ameliorating the building climatic catastrophe and reduce the likely huge refugee flows that will transform the entire global epidemiological environment.

The U.S. should aid China to reduce that nation’s huge pig-duck-pond-wildlife market, which is a lethal virus manufacturing machine. Putting pigs and ducks together with ponds is bad in itself, but adding wildlife markets to the mix makes it worse – and it’s an important factor in the global epidemiological environment.

America and China could lead a civilization-wide program to halt the destruction of biodiversity – another factor which negatively impacts that environment.

What I’m basically saying is that the U.S. should fix the epidemiological environment by taking the obvious steps to solve the human predicament – to avoid the collapse of civilization now entrained.

Teaching planetary literacy

This seems wildly optimistic in a world that has not even recognized its problems of overpopulation and overconsumption or the impacts on health and well-being of socio-cultural regression: rising xenophobia, racism, religious prejudice, sexism, and, especially, economic inequity.

What explains this?

There are the causes usually noted, such as the power of money, not just in politics but in global culture as a whole. But a major element is widespread ignorance, partly due to broken educational systems – allowing, for example, mobs of innumerate economists, politicians, and decision-makers in general to believe in perpetual growth in population and consumption.

The widespread inability of “educated” people to think is frequently underlined by statements on how “we don’t have a population problem, just a problem of too much consumption.”

Can’t they grasp the not-so-difficult idea that a billion people are likely to consume more than a hundred? Case in point on the ignorant “educated”: Donald Trump got a B.S. in economics from the Wharton School of my alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania.

To overwhelm this vast ignorance demands resuscitation of our higher education system. Universities and colleges remain stalled in a 19th century Aristotelian state. They have given up any goal except turning out people who will be financially successful in a deteriorating culture — oiling parts of the engine with never a thought for where the train is heading.

And that “education” clearly doesn’t even give its products a grasp of such concepts as exponential growth, as the response of Trump and many others to the COVID-19 epidemic have shown.

Educational systems have given up any pretense of supplying leadership to society or informing people about what is coming down the track. Faculty members discuss “sustainability” in major universities that will not even divest from fossil fuel stocks.

Can the absence of a draft alone explain the difference between the ferment in universities during the Vietnam War and the quiet today with the situation a million times worse?

Once again, population size and growth are major factors in this human dilemma – maybe Homo sapiens shouldn’t have tried to organize itself into groups exceeding the Dunbar number, which anthropologist Robin Dunbar showed was about 150 people, the size of hunter-gatherer groups. He also showed that’s roughly the size of groups in which human beings are comfortable today.

Rethinking resources

Where could all the money come from to make the changes to preserve civilization? That’s one of the challenges for the economists who today are operating in a perpetual-growth fairyland.

Much depends on the course of events and whether the debt pyramid collapses. One obvious step, however, is repurposing the military. When Anne and I were working with them on nuclear winter issues, we were greatly impressed by the intelligence and ethics of some of the field-grade officers with whom we were involved.

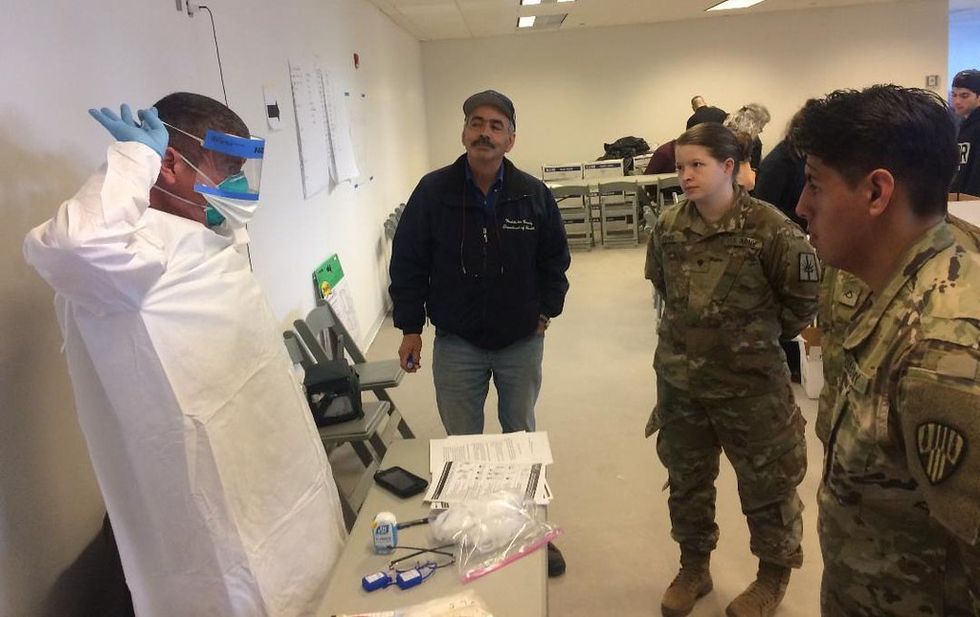

The military is already way ahead of the present civilian government in addressing existential threats like climate disruption. Various military units have already been deployed to deal with emergencies ranging from pandemics to hurricanes, and there is no reason why they cannot be used to help in tasks ranging from building medical isolation facilities to small-scale affordable housing for the homeless.

Allocation of resources is part of the epidemiological environment. The gigantic amounts of money wasted on such nearly useless toys as nuclear weapons, aircraft carriers, main battle tanks, and air superiority jet fighters could be redirected toward rebuilding infrastructure such as sewage systems, modernized electric grids and water-handling networks, and on and on.

The same can be said for the other funds and activities used for decades to support (often clandestinely) U.S. state terrorism that has cumulatively killed millions since the second World War.

Is all this impractical, pie-in-the-sky, never-happen stuff? Sure.

But nothing is more impractical than civilization trying to continue business as usual as it circles the drain.

The current pandemic disaster may end up damping down consumerism and improving the environment – there are reports of the lethal smog usually blanketing some Chinese cities clearing during pandemic lockdowns.

Maybe there’s some chance that people are learning lessons.

We can always hope.

Paul Ehrlich is the Bing Professor of Population Studies, Emeritus and President of the Center for Conservation Biology at Stanford.