Appalachia’s fracking boom has failed to deliver on promises of jobs and benefits to local economies, according to a new study.

The study, published today by the Ohio River Valley Institute, a nonprofit think tank, revealed that while economic output in Appalachian fracking counties grew by 60 percent from 2008-2019, the counties’ share of the nation’s personal income, jobs, and population levels all declined. The analysis concluded that about 90 percent of the wealth created from shale gas extraction leaves local communities.

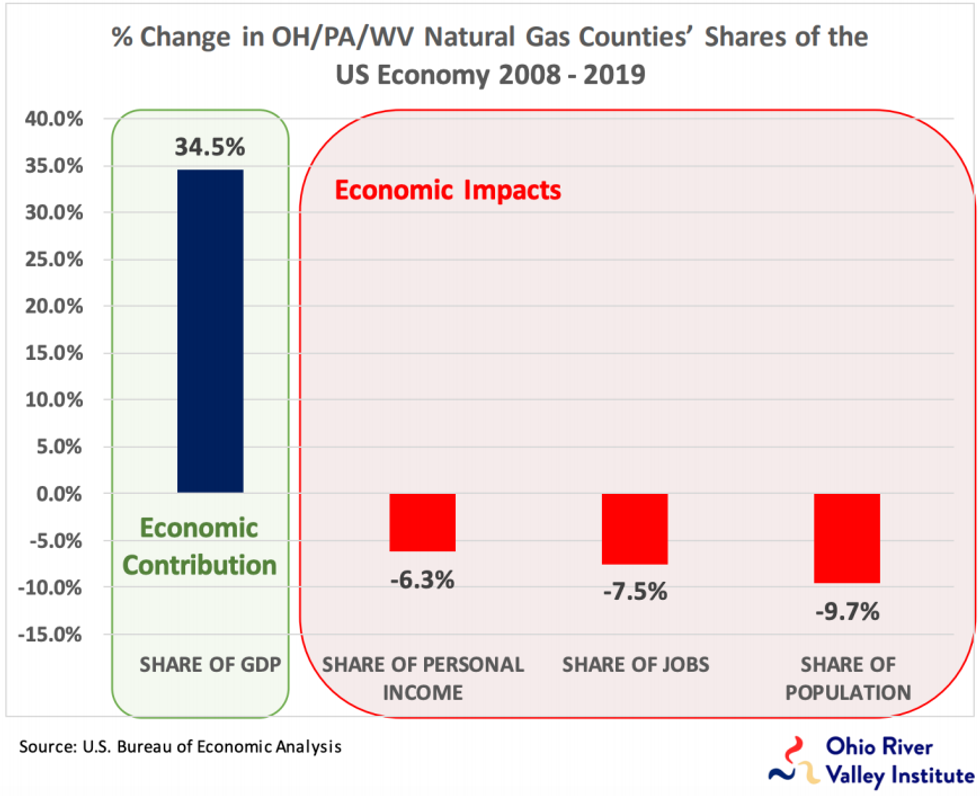

The study looked at the 22 counties in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia that produce more than 90 percent of the region’s natural gas. In 2008, those counties were responsible for $2.46 of every $1,000 of national economic output. By 2019, the counties were generating $3.31 of every $1,000 generated nationally—an increase more than triple the rate of national growth. But over the same period, those counties’ share of the nation’s personal income fell by 6.3 percent, their share of jobs fell by 7.5 percent, and their share of the nation’s population fell by 9.7 percent.

“This report documents that many Marcellus and Utica region fracking gas counties typically have lost both population and jobs from 2008 to 2019,” John Hanger, former Pennsylvania secretary of Environmental Protection and policy director to Governor Tom Wolf, said in a statement. “This report explodes in a fireball of numbers the claims that the gas industry would bring prosperity to Pennsylvania, Ohio or West Virginia. These are stubborn facts that indicate gas drilling has done the opposite in most of the top drilling counties.”

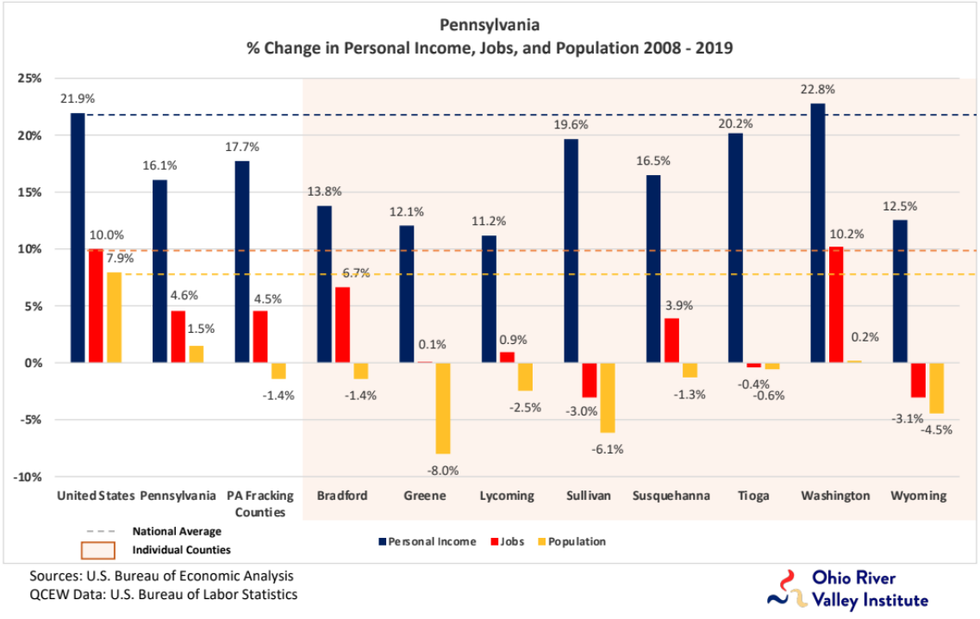

Among the three states the report looked at, Pennsylvania’s showed the best prosperity measures: GDP growth in Pennsylvanian fracking counties was two and a half times as high as the national level and four times as high as the state’s. Personal income growth was slightly lower than the national average, but slightly better than the state average.

But jobs growth in Pennsylvania’s fracking counties was less than half the national rate and about the same as the state as a whole.

Some Pennsylvania counties performed better than others—Washington County fared the best, with a personal income growth rate that slightly exceeded national growth, and job growth equal to the national rate. Tioga and Wyoming counties also exceeded the state average, but not the national average for personal income growth. But five of the other seven Pennsylvania counties either gained very few jobs or experienced a loss.

Negative cash flows and health harms

According to the Ohio River Valley Institute’s analysis, only about 10 percent of the wealth created from shale gas extraction stays local. But despite 90 percent of that wealth leaving the region, oil and gas companies have also struggled to stay afloat: More than 250 oil and gas producers have filed for bankruptcy since 2015, and the industry shed more than 100,000 jobs in 2020 alone.

The process of extracting oil and natural gas from the Earth by drilling deep wells and injecting liquid at high pressure is expensive and many fracking companies go into a tremendous amount of debt getting started. Due to oversupply and consistently low prices for natural gas over the last 10 years, many have yet to pay those debts back.

“These companies are producing gas, but they still haven’t figured out how to make this profitable business—they’ve had negative cash flows year in and year out,” Kathy Kipple, a financial analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis and instructor at Bard College, said during a recent Ohio River Valley Institute forum. “There has been no business case for fracking.”

Meanwhile, evidence that fracking harms communities nearby continues to mount. As of August 2020, there were 2,015 studies indicating harm or potential harm from fracking, according to a literature review conducted by the health advocacy groups Physicians for Social Responsibility and Concerned Health Professionals of New York. The health impacts range from headaches, nosebleeds, and asthma exacerbations to anxiety, depression and increased risk of birth defects and premature births.

Hanger said during the same forum that policymakers have had blind spots when it comes to the oil and gas industry.

“This is a story I’ve heard over and over in my 30 years of being involved with policy-making—it starts with good people who are desperate for economic development, very well intentioned, and looking to create jobs,” he said. “But unfortunately that kind of motivated thinking often ignores stubborn facts.”

The death of the petrochemical dream?

A few years into the fracking boom, once it became clear that it would be difficult to turn a profit through natural gas extraction, companies began looking for ways to salvage their investments.

Ethane, a byproduct of fracking, is used to manufacture plastics, so many oil and gas companies looked to building plastics manufacturing plants that would create new demand for ethane.

Gas extracted from Appalachia is particularly high in ethane, so the dream of an Appalachian petrochemical hub emerged, with at least five companies proposing to build petrochemical facilities, underground storage hubs, and hundreds of miles of pipelines in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, and West Virginia. Each site was estimated to create demand for ethane from 1,000 new fracked wells each year.

In 2017, a report from the American Chemistry Council projected that by 2025, this Appalachian petrochemical buildout would create over 100,000 jobs—roughly 25,000 directly employed by these and other plastic manufacturing facilities and an additional 75,000 indirect jobs like contracted delivery drivers, construction workers, and retail workers. It also projected $500 million in state and local tax revenues from the industry.

But now those plans are falling apart.

Of the proposed projects, only one is actually underway: The Shell ethane cracker in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, about 33 miles northwest of Pittsburgh. That facility was supposed to be operational by 2020, but construction was slowed due to COVID-19 and is still in process. The rest of those projects are on hold indefinitely.

Two major things changed shortly after the American Chemistry Council published its 2017 report: In 2018, China stopped taking U.S. plastic to recycle, and a powerful group of companies that sell products in plastic packaging, including Nestle, Unilever, and Colgate-Palmolive, announced plans to drastically cut their use of virgin plastics by 2025 (a pledge that has since been formalized through the U.S. Plastics Pact).

“Those two things were a huge stop,” Anne Keller, a former Wood-Mackenzie petrochemical analyst and industry consultant, said during the forum. “They challenged growth assumptions not just about the U.S. or China, but the entire market.”

The price of plastics fell (down from about $1 per pound in 2012 when these petrochemical proposals were being launched to about 40 cents per pound in 2020) and some financial analysts now say it’s unlikely that petrochemical development will save the fracking industry—or the local economy.

“The financials do not support the contention that petrochemical development will help,” said Kathy Hipple, finance professor at Bard College and former financial analyst at the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). She noted that building petrochemical facilities costs billions of dollars and takes a long time, so companies have to gamble on what the future of the market will look like by the time such a project is complete—and at present, that future doesn’t look promising.

“At this point I don’t believe Shell will hit their financial targets or produce the kind of economic benefits that were initially promised to the state,” she said. “I think that’s why other companies have not rushed in.”

Hipple added that resistance from local communities increasingly shows up in oil and gas financial reports and disclosures.

“More and more we’re seeing from earnings calls and financial reports that local opposition has become a material risk factor,” she said, adding that when it comes to foreign companies looking to get in on a petrochemical buildout, understanding the patchwork of local state and federal regulations is complicated enough without the addition of lawsuits from community groups challenging every step in the permitting process.

“For those in the community wondering if their efforts are bearing fruit,” she said, “I believe they are.”

Investor flight

Some economists remain confident that the price of oil has always been volatile, and that markets will return to normal in the long-term. But Hipple noted that investors have begun to turn away from fossil fuels and virgin plastics, pointing to coal as an example.

“Coal companies have lost 90 percent of their market value even though coal production has only declined 1.5 or 2 percent,” she explained. “The market is forward looking…and investors know that industry will not continue to buy virgin plastics.”

Hanger added while consumers have benefitted from the low cost of natural gas, many investors lost money in shale gas development, and are instead looking to what the European oil and gas companies are doing next.

“If you look at the majors in the European oil and gas industry like BP and Total and Equinor, they’re all moving into clean tech of one sort or another, making investments in electric charging networks, offshore wind, and solar,” he said.

“This is not the Sierra Club,” he added, “it’s oil and gas companies. To double down or triple down on the shale gas vision or oil and gas industry isn’t even being done by industry at this point…Public money should be synergistic with private investment money. Legislators and economic development folks should follow their lead.”

Hipple agreed. “It’s difficult to sit on a natural resource and not think it’s a ticket to economic development,” she said, “but it’s important to step back and take a cold hard look at economic facts. When you’ve got 11 years of negative cash flows in the fracking industry…it’s not producing jobs, and benefits are not accruing to local communities, it’s really time to step back, take a cold-hearted look, and see what the market is telling us.”

“Simply put,” she said, “the natural gas industry has not delivered the promised benefits for producers, investors—or local communities.”

Banner photo: Drill rig in Beaver, Ohio. (Credit: FracTracker Alliance/flickr)