I’m a Black woman with a doctorate in environmental health. For six years, I was the only Black doctoral student in my department.

In post-graduate life, my close network of Black professionals in the environmental field is now slightly larger. It has grown from one to four.

We scrutinize new “clean” beauty products, pass along interesting podcasts, and expand each other’s professional connections. Importantly, we provide a safe space to discuss workplace issues.

In a recent conversation, Danielle (not her real name), an attorney whose practice focuses on the intersection between environmental justice and law, was sharing her latest struggles as a woman of color in an environmental organization. She is passionate about her work, but workplace mistreatment was leaving her mentally and emotionally exhausted and causing her to question whether she had a future at this organization.

The struggles that people of color face at work are well-documented and pervasive, often beginning before they’re even hired. White-sounding names and lighter-skinned applicants are often more successful in getting hired. Once employed, the day-to-day work can involve dealing with microaggressions,

gaslighting, and tone policing. The result is an environment where people of color feel uncomfortable and unsafe. It is no surprise that fewer Black women were interested in returning back to the office than their white counterparts after more than a year of remote work due to COVID-19.

This essay is part of “Agents of Change” — see the full series

The topic of environmental justice itself can take a toll on people of color working on these issues. Advocating for communities harmed by environmental policies can be difficult, especially if you are a member of that community. The work becomes more challenging if the workplace culture does not respect people of color or see value in environmental justice work. The combination of a racially stressful work environment plus the heaviness of emotional connection to the work can leave staff of color struggling, both emotionally and physically.

At the end of the conversation, Danielle asked, “but where would I go?”

Addressing racism in environmental organizations

As a young scientist in the final year of my postdoctoral training, I am asking a similar question. I have years of expertise investigating how chemicals in consumer products negatively affect human health and, in my current work, I focus on how these chemicals disproportionately affect people of color. While I am still deciding what my next career steps will be, I hope my research contributes to and supports advocacy work that prioritizes chemical safety and environmental justice.

I cannot help but wonder if Danielle’s struggles will eventually be my own. Last year, the country was forced to reconcile with its racist history. While many environmental organizations and agencies — such as non-profits, federal and state agencies — are now addressing environmental racism in their work, that doesn’t always immediately translate down to employees and the workplace cultures. In looking at these potential employers, I wonder if the culture within has shifted. I wonder how I’d engage in environmental justice work while navigating the uncomfortable reality of discrimination at my future workplace.

This essay is also available in Spanish

Dr. Jill Lindsey Harrison, a sociologist who focuses on environmental justice, describes how the culture of U.S. agencies hinders environmental justice work in her book, “From the Inside Out.” Harrison interviewed staff from multiple environmental agencies operating at the federal, state, and local levels of government — from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to city agencies with environmental justice programs — and found that their work is sometimes hindered by their own colleagues. For example, proposals for environmental justice work or recommendations by environmental justice staff were dismissed or ignored as being outside of the agency’s identity or agenda. In other instances, staff criticized environmental justice reforms using “prejudiced arguments” that suggest that working class communities and historically excluded communities don’t deserve the benefits from environmental justice programs. While Harrison’s work is merely a snapshot, it is easy to see how this culture can be discouraging, uncomfortable, and isolating for staff of color.

Identifying these unhealthy work environments while job searching is difficult. While it is not always easy to recognize a toxic work environment, seeing a lack of diversity amongst staff or leadership is a red flag for me. Despite environmental organizations hiring more people of color, the field is still grossly lacking in diversity. There is a higher turnover of people of color at environmental organizations. A recent report showed that staff of color at environmental organizations felt like they had fewer opportunities for development and promotion at their jobs, which made them feel more inclined to leave the organization. Hiring without committing to inclusive practices means organizations are not making meaningful progress towards the diversity issue, particularly at the leadership levels.

Emotional toll of environmental justice work

Addressing racism is currently at the forefront of the environmental health field, for the first time in a long time. For example, this past spring Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael S. Regan directed all offices to integrate environmental justice into all agency actions and plans. This means attorneys are mandated to hold polluters accountable for environmental violations against over-polluted communities, and scientists should consider all aspects of a community when assessing health impacts.

For the people of color tasked with doing this work, I imagine it feels personal. Communities overburdened by pollution are often majority Black and Brown. As a result, people of color integrating environmental justice into their work may feel emotionally invested because they can relate. In my previous job as an environmental health consultant, I often worked on toxic tort cases, where a person or group of people sought legal action after exposure to a chemical in a product made them sick. The company I worked for was frequently employed by the defendants — usually the company or producer of the product. When the plaintiffs were people from marginalized communities, I often felt conflicted and uncomfortable. Eventually, I declined invitations to work on these projects to spare myself the stress.

My friend Danielle described how colleagues belittled her work focusing on over-polluted communities and rolled their eyes and sighed when she inquired about hiring more attorneys of color. She expressed how thankful she was to not be working in her hometown, New York City, because the disregard from staff would feel like an attack on the community where she grew up, an attack she fears she would not be able to handle. The stress of trying to promote environmental justice while dealing with intolerance and discrimination takes a toll.

Balancing work and well-being

When I think about the unique situation that environmental justice staff of color face, I think of weathering, which is the way repeated social or economic adversity and political marginalization can lead to premature aging and health problems for Black people. This is the combined wear and tear on the body as a result of repeated stressors, such as being mistaken as part of the company’s janitorial staff or being told that you are “so well spoken” after finishing a presentation to your department. Researchers can measure this stress using markers such as blood pressure, body mass index, or protein levels that indicate inflammation. Weathering can explain, in part, why Black people experience disproportionately higher rates of heart disease, hypertension, and obesity.

The issues that environmental justice staff of color face go beyond normal work stress because of how personally intertwined the discrimination is with the motivation of their work — it all becomes personal. And that is why staying in a job like that feels right, despite the challenges. I chose this field because I believe that everyone has the right to safe and clean places to live and work.

Returning to Danielle’s question — where could she work and not face these problems? That is a question that I don’t have any answer for, but it is an important one.

The decision for us and other people of color is complicated — how do we balance our own personal safety and wellbeing with the drive to pursue environmental justice?

Lariah Edwards is a postdoctoral scientist working jointly at the George Washington School of Public Health (GWSPH) and the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). She can be reached on Linkedin or on Twitter at @lariah_e.

This article was produced through the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice fellowship. Agents of Change empowers emerging leaders from historically excluded backgrounds in science and academia to reimagine solutions for a just and healthy planet.

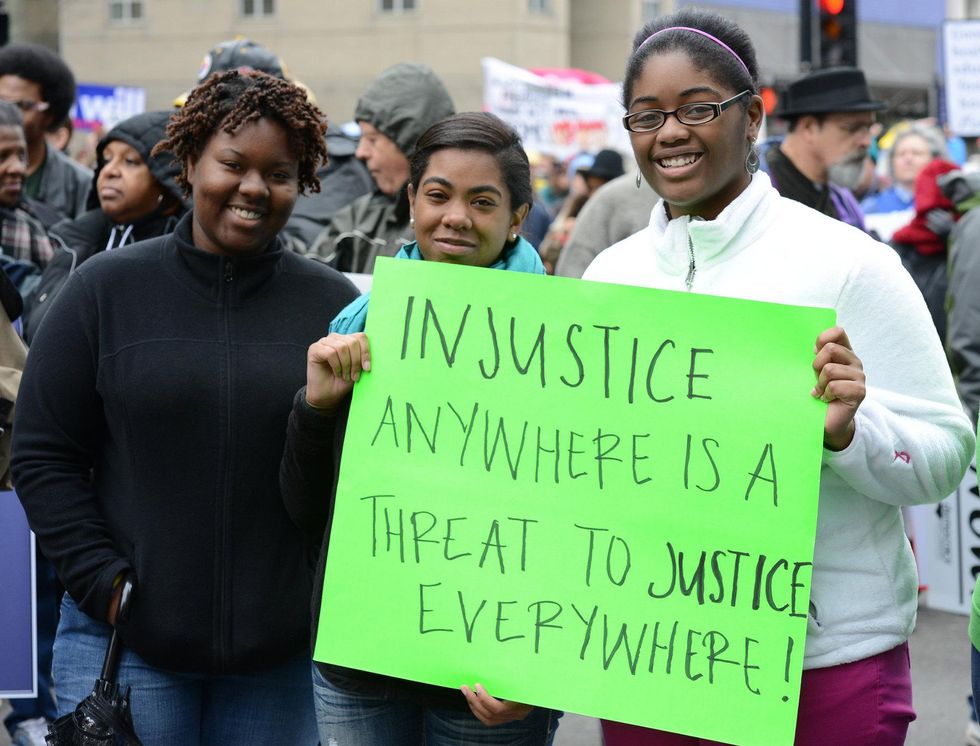

Banner photo: A march against climate injustice at COP25 climate talks in Madrid, 2019. (Credit: Friends of the Earth International/flickr)