This is a republishing collaboration with Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, where this originally published. See the full series, Caribbean People at Risk from Sargassum Invasion.

Schools evacuated due to toxic gas. Smelly tap water at home. Tourist operators and fishers struggling to stay in business. Job losses. Power outages affecting tens of thousands of people at a time. Dangerous health problems. Even lives lost.

To read a version of this story in Spanish click here. Haz clic aquí para leer este reportaje en español.

Such crises were some of the consequences of sargassum in the islands of the Caribbean in 2023, and they have become common in the region since 2011 when massive blooms began inundating the shorelines in the spring and summer months.

On April 18, 2023 in Guadeloupe, the air-quality monitoring agency Gwad’Air advised vulnerable people to leave some areas because of toxic levels of gas produced by sargassum. Six weeks later, about 600 miles to the northwest, sargassum blocked an intake pipe at an electricity plant at Punta Catalina in the Dominican Republic. One of the facility’s units was forced to temporarily shut down, and a 20-year-old diver named Elías Poling later drowned while trying to fix the problem.

In Jamaica, during the months of July and August, fishers found themselves struggling through one more season as floating sargassum blocked their small boats and diminished their catch.

“Sometimes, the boats can’t even come into the creek,” said Jamaican fisherman Richard Osbourne. “It blocks the whole channel.”

In the British Virgin Islands (BVI), most of Virgin Gorda’s 4,000 residents had to deal with sporadic water shutoffs and odorous tap water for weeks after sargassum was sucked into their main desalination plant last August.

And in Puerto Rico, a highly unusual late-season influx inundated the beaches of the Aguadilla area for the first time, leaving residents like Christian Natal and many others out of work for a week when it shut down businesses including the jet ski rental company that employs him.

These victims are among thousands of people hurt by sargassum blooms last year alone in the Caribbean, where about 70% of the population of around 44 million lives near the coast, according to the World Bank.

Scientists blame the explosive growth of the seaweed on global pollution, climate change, and other international problems that Caribbean islands did little to cause and lack the political power to resolve.

“Seaweed must be seen as an impact of global warming, with the opening up of the right to compensation on the grounds that we are small, vulnerable islands,” said Sylvie Gustave dit Duflo, the vice-president of the Guadeloupe Region in charge of environmental issues and president of the French Biodiversity Office.

She added that the countries of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) — which include 15 member states and five associate members that are territories or colonies — recorded economic losses of about $102 million due to sargassum in 2022 alone.

“These figures do not take into account the losses recorded in all the other Caribbean countries, including the French islands,” she said. Nor do they take into account yearly costs of beach cleaning estimated to be as high as an additional $210 million.

Gustave dit Duflo and other experts say the global problem requires a global response. But so far, the Caribbean has failed to coordinate even a region-wide strategy, and the international community has largely turned a blind eye. National-level responses — which in most Caribbean countries include a draft management strategy that hasn’t been officially adopted or adequately funded — have done little to take up the slack.

Most sargassum influxes are predictable, and the worst impacts are often preventable. But again and again, Caribbean governments have waited to react until the crisis stage. And even then, the responses have often focused on protecting the tourism industry while other groups, such as local communities or fishers, are left behind.

As a result, residents’ health, livelihood and natural environment have been endangered, and hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent on reactive emergency responses that experts say could have been better spent on prevention, planning and mitigation.

At the Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP28) last December in Dubai, Gustave dit Duflo helped unveil a French proposal for the sort of international response she says is urgently needed. It includes forming a global coalition to better understand the problem, ensuring that sargassum is on the agenda of major international forums, and continuing previous work in partnership with the European Union, among other measures.

But to implement the proposal, governments in the Caribbean and further abroad will have to overcome hurdles that have previously stymied cooperation, including political and legislative differences, funding shortages, and debate about whether to prioritize health, the environment, the economy, or other areas.

In the meantime, sargassum has already started to arrive on the Caribbean’s shores once again. And once again, the region is not ready.

The ‘Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt’

Sargassum is not a bad thing in itself. Nor is it new to the Caribbean, where it has always washed ashore in modest quantities in the spring and summer, providing habitat for marine life and helping build beaches as it decays.

But 2011 brought too much of a good thing. Way too much.

Without warning that year, sargassum suddenly swamped shorelines. It piled several feet high on some beaches. It stank like rotten eggs as it decomposed. It shut down resorts, dealing a major blow to a tourism sector in some areas of the Caribbean still struggling to recover from the 2008-2009 global recession. It gave coastal residents headaches, nausea and respiratory problems. It disrupted turtle nesting sites and threatened reefs and mangroves.

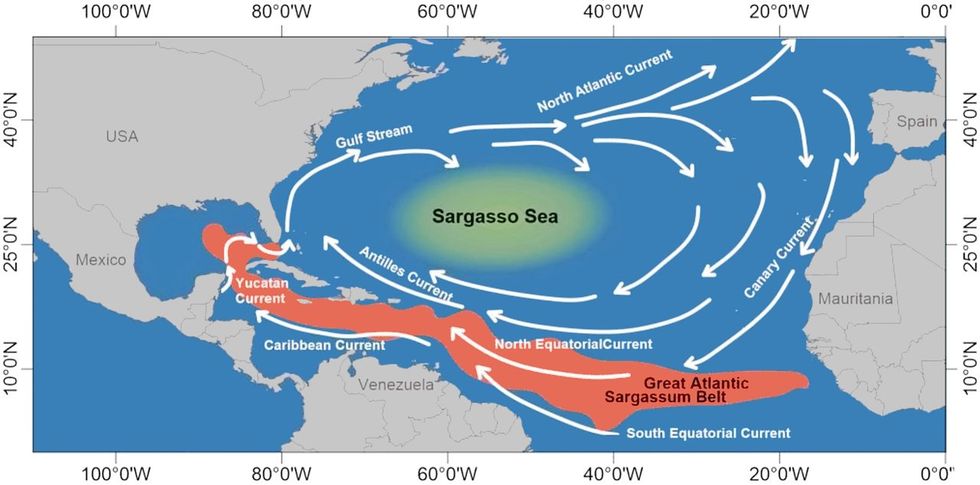

As sargassum continued to flood the Caribbean and the western coast of Africa 8,000 miles away, scientists made a surprising discovery. Historically, most of the seasonal influx in the Caribbean had come from a two-million-square-mile gyre in the northern Atlantic Ocean: the Sargasso Sea.

“The Sargasso [Sea] has been around for hundreds of thousands of years, and it’s an ecosystem that was perfect, so to speak,” said Dominican Republic oceanographer Elena Martinez. “It was there surrounded by four oceans gyres, or currents, that kept it perfect.”

But scientists soon learned that most of the new Caribbean influx wasn’t coming from the Sargasso Sea anymore: It was coming from a new sargassum ecosystem that had formed in the southern Atlantic Ocean.

The area dubbed the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt in a 2019 article in Science is now visible from space, and its length often exceeds 5,000 miles, according to scientists who use satellites to track it.

Its cause is still debated. Sargassum researcher Dr. Brian Lapointe sees the Atlantic belt as a global version of a smaller bloom he witnessed in 1991 that shut down a nuclear power plant and other electricity facilities along the Florida coast.

Since the 1980s, the world population has nearly doubled, explained Lapointe, a professor at Florida Atlantic University. This, in turn, has led to a massive increase in the sargassum-boosting nutrients washing out of major rivers like the Mississippi in the US, the Amazon and Orinoco in South America, and the Congo in Africa.

“To grow that world population, we’ve used these fertilizers; we’ve deforested along all the major rivers in the world,” he said. “The nitrogen has gone up faster than the phosphorus from all these human activities, including wastewater, sewage, from the increasing human population.”

Another likely culprit is climate change. Martinez said warming waters may have disrupted the giant gyre that held the Sargasso Sea in place for thousands of years, releasing sargassum to float south and form the new belt.

The new belt also receives additional nutrients from the Sahara dust that frequently blows across the Atlantic — which itself could be exacerbated by climate impacts such as the expansion of deserts as temperatures rise. Some scientists also argue that warming oceans provide a more sargassum-friendly growing environment.

Experts tend to agree that the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt is here to stay — and that it is a global problem that needs a global response.

‘A terrible scene for the people’

That much was clear by 2018, when the belt grew to a record size that was estimated at 22 million tons and much of the Caribbean saw its worst-ever inundation. The season spurred increasing calls for a collaborative international response.

The following year, United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres visited St. Lucia for a July meeting of the Caribbean Community, and he took a side trip to the small fishing village of Praslin Bay.

Surrounded by dignitaries, Guterres walked down a dock lined with small boats bobbing atop thick mats of sargassum, which for years had plagued fishers, sea moss farmers and other residents in the area.

“So it’s a terrible scene for the people?” he asked a resident in a video posted on the United Nations website.

“Yes,” the man responded. “It’s killing the fishes in the bay. The stench. It’s destroying our electronics because of the fumes.”

After his visit, Guterres described his sadness on seeing a “landscape that resembled an algae desert for hundreds of meters.”

Then he called for international action.

“Oceans don’t know borders, nor does climate,” he said. “It is a global collective responsibility to take action now.”

But that broad international action has not materialized as planned. Despite a growing patchwork of studies and projects across the region, various attempts by the UN and others to coordinate a Caribbean-wide response have been largely stalled by funding shortages, geopolitical issues, the Covid-19 pandemic and other factors.

One of the most extensive efforts came about three months after Guterres’ visit to St. Lucia, when Guadeloupe hosted the First International Conference on Sargassum in October 2019. Partners at the event — where the three-year Sarg’Coop program financed by about $3.2 million in European Union funds was officially launched — included the French government, the Guadeloupe Region, UNESCO and other entities. In attendance were representatives from more than a dozen Caribbean countries and territories, as well as the US, Mexico, Brazil and France.

Some progress followed. For instance, the Guadeloupe Region — in partnership with the French government, the French National Research Agency and two Brazilian agencies — launched a call for projects that enabled a dozen international studies to be carried out on the health, environmental and economic impact of the seaweed, as well as possible uses for it.

Other regional meetings have been held since then as well. Last June, for instance, an European Union-Caribbean conference on “Turning Sargassum into Opportunity” was held in the Dominican Republic, and the topic was discussed the following month at a summit of the EU and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (EU-CELAC) in Brussels, Belgium.

But almost five years after the 2019 Guadeloupe conference, the broader goals have not come to fruition on a regional level as envisioned, experts acknowledge. No Caribbean strategy is in place, and the region-wide warning and monitoring center envisioned at the conference has not been established.

Instead, many of the actions that grew out of the Guadeloupe conference have centered mainly on the French Caribbean. Funded in part by about $66 million allocated for 2018 to 2026 by the government of France — which for decades has struggled with algae washing ashore on its European coasts — the French islands have launched some of the most extensive response efforts in the Caribbean in recent years.

But even this has not been enough to protect residents.

Describing Guterres’ visit to Praslin Bay as “nothing more than a photo op,” Martinique-based professor Dr. Dabor Resiere and seven other researchers claimed in a March 2023 article that the “local authorities failed to take advantage of such an important visitor to give international recognition to the sargassum phenomenon in the Caribbean.”

Four years later, they added, the situation remained “unchanged.”

“Despite the French government’s plans to tackle the sargassum problem, these toxic algae are continuing to inundate the coasts of Martinique, Guadeloupe, and French Guiana in ever-greater volumes,” the researchers wrote in the Journal of Global Health, adding, “Today, there is no national and international consensus on facing this public health problem. There is no Caribbean network or a broad consensus to advance research at this level.”

Even Praslin Bay saw scant relief in the years after it welcomed the UN secretary general.

In 2022, St. Lucian sargassum researcher Dr. Bethia Thomas produced videos about the village and two other nearby communities as part of her doctoral thesis. In each video, several residents listed complaints ranging from breathing problems to fisheries destruction to corroding jewelry.

“It affects how I breathe, and I also think it affects the children and the way that they function, because sometimes they’re so moody and they cannot sit and do the activities because it’s so awful,” a teacher says in the video of Praslin Bay. “And I think it’s affecting us mentally.”

Concerns about sargassum’s effects on the mental health of coastal residents and workers were noted in a September 2023 report by the 34-member Western Central Atlantic Fishery Commission. “The unpleasant odor, the deterioration of their environment, lack of access to the beaches for relaxation, uncertainty about the future, increase in physical ailments such as respiratory illness and skin rashes, and concerns about other potential health risks, among other things, will naturally affect mental health,” stated the commission, a regional fisheries body established under the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization.

However, the report added that such mental health impacts are not currently being studied.

In the absence of a regional strategy, national sargassum management plans have been developed in most countries and territories in the Caribbean, including eight through grant-funded projects affiliated with the University of the West Indies in St. Lucia, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, BVI, Anguilla and Montserrat.

But few have been officially adopted at the government level, and even fewer are adequately funded or closely followed.

“Sometimes the small communities get left behind,” Thomas said. “Maybe not intentionally, but in small island developing states with limited resources, you have to prioritize. And perhaps other things — like building a new hospital and constructing new roads, new schools — might take precedence over developing a sargassum management plan.”

Partly as a result, sargassum responses can vary dramatically from island to island.

But in probing major influxes in six Caribbean countries and territories last year, CPI found one constant: people are suffering.

Negligible investment from polluting countries

As residents experience health and economic consequences, Caribbean leaders often complain about a shortage of money to deal with the crisis. Local funds, they note, are tied up with many competing priorities, including handling climate-related impacts like hurricanes, droughts and flooding.

They also say that the cost of the sargassum crisis should be shouldered in part by the larger countries mostly responsible for it, but that accessing international climate financing for the purpose is not easy.

A CPI review of projects funded by the Global Environment Facility and by members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development between 2000 and 2021 found out that of the hundreds of billions of dollars spent on climate change projects in the world, less than $7 million went to address sargassum-related issues. About 89% of those funds, or $6 million, were spent in the Caribbean.

But for many non-independent islands, the problem is compounded by a political status that renders them ineligible for most climate financing.

“We have no access to global funds: Resilience fund, the loss-and-damage fund,” said BVI Health and Social Development Minister Vincent Wheatley, whose home overlooks the Virgin Gorda desalination plant that was recently damaged by sargassum.

At the annual UN Climate Change Conferences, he explained, overseas territories are not parties and don’t have their own seat at the negotiating table.

“We fall under the [United Kingdom],” he said. “So whatever the UK negotiates, it will pass on to us.”

Therefore, he said, the BVI and other overseas territories have been in separate negotiations with the UK.

“We banded together to petition the UK to carve out a specific fund for [its] overseas territories,” he said, adding that these discussions are ongoing and include sargassum.

A lack of funding and regional coordination has also stymied efforts to monetise the seaweed by finding a large-scale sustainable use for it.

“Even though there are so many things you can make with sargassum, the actual amount of sargassum that is used for products is still very low,” said Dr. Franziska Elmer, a sargassum researcher based in Mexico.

Sargassum plan proposed at COP28 in Dubai

The 2023 sargassum bloom in the Caribbean had mostly abated by Dec. 2, when Gustave dit Duflo, the French Biodiversity Office president, stood at a podium 8,000 miles away during a side event at the COP28 meeting in Dubai.

As dignitaries looked on, she issued a stark warning about sargassum.

“It is a very invasive and aggressive phenomenon, and through all the Caribbean it affects tourism, and all the economies of the region are based on biodiversity and tourism,” she told those gathered at the French pavilion on the sidelines of the conference. “The Caribbean has a lot of hot-spots of biodiversity. So if we don’t act, in 20 years this marine biology, including the reef, will disappear from our coast.”

She then explained the French government’s proposal to address the issue. The program, she said, has four prongs: forming an international coalition to better understand the problem and its causes; addressing sargassum in international forums like the COP of Biodiversity; acting in the framework of the Cartagena Convention; and working with the EU to support the continuation of the regional Sarg’Coop project launched during the 2019 conference in Guadeloupe.

The French government has presented the proposal as an unprecedented move at COP 28, with the aim of placing the sargassum issue on one of the high-level panels of the United Nations Conference on the Oceans to be held in Nice, France, in June 2025.

Such collaboration is essential, according to Gustave dit Duflo.

“We manage sargassum at a local level, but this is not a phenomenon of an island. It is the whole basin of the Caribbean and a part of the Atlantic,” she said. “This is why all the countries that are impacted, we need to create an international coalition to be able to find means and ways to act.”

Since COP28, the Netherlands and its overseas countries and territories decided to join the international program proposed by France alongside Costa Rica, Mexico, Dominican Republic and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States, Gustave dit Duflo told CPI.

A meeting will be held soon with the European Commission to define the project’s legal guidelines and financing, she said.

Also at COP 28, the EU and the government of the Dominican Republic co-organised a related panel at the Dominican Republic pavilion, where they launched an initiative to “turn sargassum into an economic opportunity” by tapping the EU-Latin America and the Caribbean Global Gateway Investment Agenda.

To succeed, such projects will need to build on work that came out of efforts like the 2019 conference in Guadeloupe — and overcome the challenges that delayed them.

Since early 2019, for instance, Météo France, the French weather service, has been operating a sargassum monitoring and detection service in the French West Indies and French Guiana. But so far, these efforts have not expanded into the regional center envisioned at the 2019 conference despite various monitoring systems launched in recent years, such as the Jamaica Early Advisory System, the regional CARICOOS tracker in Puerto Rico, and the Satellite-based Sargassum Watch System at the University of South Florida.

The Sarg’Coop program launched at the 2019 conference also planned to replicate work done in Martinique, which in 2015 had set up a hydrogen sulfide and ammonia monitoring system that was later developed into a large-scale measurement network and extended into Guadeloupe in 2018.

Under Sarg’Coop, the Martinique-based research institute Madininair was given responsibility for supporting St. Lucia, Dominica, Tobago, Cuba and Mexico in preparing similar networks. But the Covid-19 pandemic delayed progress, and only recently did the effort get back on track with work carried out in each of those countries.

Asked about the past obstacles to implementing a common international strategy, Gustave dit Duflo, also a lecturer in neuroscience at the University of the West Indies, pointed to geopolitics. As one example, she cited the May 2023 summit of the Association of Caribbean States in Guatemala. The summit discussions, she said, were largely dominated by the conflict in Ukraine as countries in the region debated the issue of supporting Russia or the United States.

Regional collaboration has also been hindered by legislative differences across borders, according to the scientist.

Guadeloupe senator Dominique Théophile made a similar observation when he was commissioned to conduct a study on sargassum management strategies in the Caribbean ahead of the 2019 conference. After several trips to St. Lucia, the Dominican Republic and Mexico, he found that the most successful area management plans were carried out by major hotel groups on a local scale.

But such strategies often could not be deployed throughout the entire Caribbean.

For instance, health and environmental laws in French and other European territories precluded a practice that is common elsewhere in the region — spreading sargassum behind beaches — because of the possibility that the seaweed could contain arsenic and other heavy metals that could affect the ocean or groundwater.

Because of such laws, Théophile explained, the French sargassum management strategy attaches heightened importance to health and environmental impacts. Often for financial reasons, other countries’ initiatives don’t address such environmental and health considerations in corresponding detail, he said.

As countries work to rectify such issues and establish an international response, time is of the essence for residents of the coastal Caribbean.

Shortly after the COP28 drew to a close, scientists at the University of South Florida estimated the sargassum floating in the tropical Atlantic Ocean at about five million metric tons, compared to a December average of about two million. By February, the mass had increased to some nine million tons — the second highest quantity ever recorded for the month.

In other words, another record-setting sargassum season could have just started.

Reporters Rafael René Díaz Torres (Centro de Periodismo Investigativo), Mariela Mejía (Diario Libre), and Hassel Fallas (La Data Cuenta) collaborated in this investigation.

This investigation is the result of a fellowship awarded by the Center for Investigative Journalism’s Training Institute and was made possible in part with the support of Open Society Foundations.