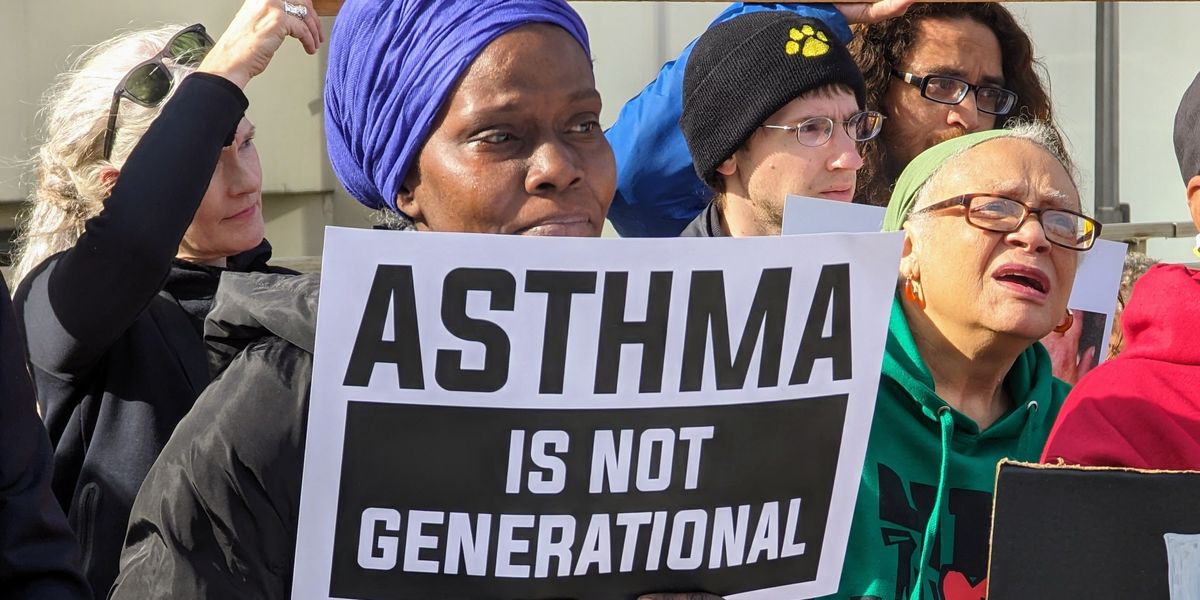

PITTSBURGH —“Will your grandkids forgive you?” “Stop hurting us,” “Asthma is not generational,” and “Cancer is not normal” were just a few of the messages delivered by protestors outside a meeting of steel industry executives on Wednesday afternoon.

The MetCoke World Summit is an annual gathering for leaders in the coke, coal and steel industries. Coke is a key ingredient in steelmaking that involves heating coal to extremely high temperatures. The Pittsburgh region is home to a network of steelmaking facilities, including U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works, which is the largest coke-generating facility in the country.

Emissions from the coke and steel manufacturing process are toxic, and southwestern Pennsylvania communities near these facilities have long suffered from health issues associated with exposure to this type of pollution, including elevated rates of childhood asthma, COPD and other respiratory diseases, heart disease and cancer.

Around 45 protesters gathered outside the hotel where the MetCoke World Summit took place, including residents who live near the region’s steel plants and residents of East Palestine, Ohio, the site of a catastrophic train derailment and environmental health disaster last year that was caused by Norfolk Southern, one of MetCoke World Summit’s 11 corporate sponsors. A series of speakers delivered messages to the crowd and the executives meeting in the hotel suites above.

“Today we’re here to serve notice on all of you that we are here to stay,” said Archbishop Marcia Dinkins, founder of the Black Appalachian Coalition. “We are here to fight… and it’s not just going to be some of us. It’s going to be all of us, and then some.”

A spokesperson for Smithers, the company that hosts the MetCoke conference, said “we don’t have a position” on the concerns raised by the protesters and declined to comment further.

”I’ve had to live in fear and uncertainty and in danger”

Several protestors from East Palestine, Ohio, held posters with enlarged photos of wounds on their childrens’ arms, legs and faces that they say resulted from Norfolk Southern’s toxic chemical disaster.

Hilary Flint, a former resident of East Palestine, Ohio and a member of the community advocacy group Unity Council East Palestine, said her great grandparents originally purchased her family’s land and she was the fourth generation to live in the family home. She said that after the spill she was told her home was safe, but paid for independent testing that found toxic chemicals including vinyl chloride, ethyl hexyl acetate and dioxins. She had to take a second job to afford relocating her family.

“Since February, I’ve had to live in fear and uncertainty and in danger,” she said. “I’ve had to give up all that I enjoy to fight for justice for myself, for my family and for my community. I wouldn’t wish this disaster on anyone else, and I don’t want your community to be next.”

Angelo Taranto, a member of the environmental health advocacy group Allegheny Clean Air Now, shared that he used to live downwind of a nearby coke plant that shut down in 2016. Research has shown that levels of sulfur dioxide, a byproduct of cokemaking linked to respiratory and heart problems, decreased by 90% after the plant shut down, which resulted in 42% fewer emergency room visits for heart attacks and 38% fewer ER visits for asthma attacks in surrounding communities after the plant’s closure.

“County officials, health department officials, heard the story of many residents who were being harmed by this,” Taranto said. “But we never did get that better regulation. In 2016 the company voluntarily shut down… Communities downwind from coke plants shouldn’t have to wait until the plants voluntarily shut down to get the types of health benefits that we got.”

Political winds shift

The rally took place the day after Allegheny County, which encompasses Pittsburgh and is home to several of the region’s largest industrial polluters, elected Sara Innamorato as its new county executive.

Community advocates have long complained that the county’s major industrial polluters operate under a “pay to pollute” model because it’s cheaper to pay the fines levied against them for repeatedly violating clean air laws than it would be to clean up their operations — a practice Innamorato pledged to end during her campaign.

NaTisha Washington, a longtime environmental justice advocate and newly elected councilwoman for Wilkinsburg, said on social media that Innamorato’s election gives her hope for the future, particularly when it comes to the health of the environment. Speaking at the rally, Washington said she’s tired of the companies that pollute local communities saying they’re environmental stewards and good neighbors.

“I’m over it, and I’m sick of it, and that’s why I became a politician,” Washington said. “We’re all here asking our politicians, our decision makers, the people that have the money that’s supposed to be owed to us, the people that have the power over the land that’s supposed to be owed to us, to finally do their jobs.”