ALBANY, NY—We descended stairs into the basement and swung open metal doors. In some ways, the animal autopsy lab at the New York Department of Environmental Conservation looks exactly how you might expect, with stainless steel benches and fluorescent lights.

Kevin Hynes, my guide for the day, explained that this was one of several rooms where his team investigates animal deaths. Hynes, a wildlife biologist, has worked in these labs for almost 30 years, where researchers track diseases and learn how humans affect animal populations. He’s studied everything from salamanders to moose, and the data is used to inform management practices and rules statewide, and serve as evidence in poaching and poisoning cases.

The bald eagle population has been an area of focus for the lab, and Hynes personally, for decades. The team has watched eagles because of their protected status, and the monitoring efforts have made clear the challenges facing bald eagles today, especially from lead poisoning.

Lead poisoning in wildlife

The day I visited, another DEC research scientist, Ashley Ableman, was scheduled to autopsy a young bald eagle, not yet sporting the white head-feathers of an older bird. This eagle had been found on the side of the road near a landfill. On the X-ray taken before the examination, bright white spots had appeared in the stomach—an indicator of metal inside.

The biologists’ first thought was lead, Hynes explained, as the lab often sees birds with lead fragments in their stomach, usually from lead ammunition used in hunting. Rarely are the eagles the direct target of bullets—they’re usually collateral damage. When hunters shoot a larger animal like a deer, the bullet breaks apart when it hits the target: An animal that’s been shot can have up to hundreds of tiny fragments in their body. While hunters usually take their kills with them, they often remove the organs, leaving gut piles for scavengers to snack on, lead and all.

Unfortunately for opportunistic eaters, lead is toxic. Just one or two tiny pieces can kill an adult bird. “It really doesn’t take much,” Hynes told EHN.

The effects of lead poisoning can vary depending on exposure, but they’re often devastating. “Lead impacts every system in the body,” Krysten Schuler, a wildlife ecologist at the Cornell Wildlife Health Lab, told EHN. Exposed birds can go blind, lose their ability to digest food, and struggle to fly, along with a litany of other issues.

Lead poisoning isn’t always fatal, but even in low levels, it can harm birds’ ability to move and survive in the wild. And while eagles, along with a couple of other species like condors and loons, have been carefully studied, it’s likely that other animals are affected by lead poisoning too, said Schuler. Trail cameras often show other scavengers like crows, hawks, coyotes, and more, picking at gut piles.

Most eagles brought into rescue centers across the U.S. are tested for lead, Nicole Lewis, a wildlife veterinarian at the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Fish and Wildlife, told EHN. These centers can treat birds with lead exposure through a process called chelation therapy, although it can be lengthy and expensive. And in high enough doses, lead can kill a bird within just a few days, before any rehabilitation is possible.

In the autopsy room, Ableman checks for signs of lead poisoning, weight loss and bile staining near the tail. After unfolding the bird’s wings, Ableman carefully sliced down the center of the bird’s chest, peeling it open. She methodically cut out organs, running her gloved hands around over the rib cage, feeling for breaks.

Related: The campaign to keep toxic lead in hunting ammo and fishing tackle

She explained her process to me as she worked, throwing ideas around with Hynes. One clue she pointed out was that the eagle’s lungs were dark with blood instead of pink and fluffy: a sign of trauma. But there were no obvious breaks in the ribcage or the skull, so Ableman turned her attention to the stomach. She was going to search through the contents, looking for those metal fragments that had lit up the X-ray. Figuring out what those were could be the key to understanding what had happened.

U.S. eagle populations

Bald eagles were nearly wiped out in the late 20th century by habitat destruction and DDT, a widely used pesticide that has lingered in the environment long after it was banned in 1972. In 1963, only 417 known breeding pairs were left nationwide. From this all-time low, eagle populations grew to more than 70,000 in 2009, and then quadrupled over the next decade, reaching more than 300,000 individual birds in the U.S. by 2020.

But there are still plenty of preventable deaths, Hynes explained, some of them coming from lead poisoning. A study earlier this year reported lead ammo has reduced population growth in Northeast U.S. bald eagles by 4% to 6% annually since DDT was banned. It was like “a foot on the brakes” of the eagle population, said Schuler, who was a co-author of the study.

The non-lethal impacts are even more widespread. One recent study, published in February in the journal Science, examined 1,200 bald and golden eagles across 38 states and found that nearly half of the birds showed signs of lead poisoning.

New York State has monitored all eagles found dead for decades. Today, about 13% of eagles found dead in New York and examined by the wildlife health program are the victims of lead poisoning. It’s not the leading cause of death from human causes in the state—more than 30% are hit by either cars or trains.

There are multiple ways that wildlife might encounter lead, but the most common exposure route is through lead ammunition from hunters, Hynes said. His office typically sees cases go up in the late fall after deer season starts and taper off in the spring.

“Most hunters have no idea this is happening. It’s not on their radar, and they just don’t know about it,” Hynes said.

Lead shot for waterfowl hunting was banned in 1991. Lead ammunition is still used for other hunting today, although some organizations have called for wider lead ammunition bans. California enacted one in 2019, largely because of lead poisonings in the highly endangered California Condor population. But hunting groups have often opposed such measures, sometimes resorting to misinformation techniques to cast doubt on the growing body of research showing how lead impacts wildlife.

Protecting wildlife

After we had given Ableman time to sort through the eagle’s stomach contents, Hynes and I descended back into the basement. She’d pulled out tiny fragments from the stomach—each smaller than a grain of rice. We took them to the microscope, and Hynes made the diagnosis: not lead. It was aluminum foil, probably something the bird had gotten into in the landfill.

They still planned to send out samples to their partner toxicology lab at Cornell, where researchers test tissues for diseases and for contaminants.

The results came back a few weeks later. The lab didn’t detect lead in the samples, and the bird’s cause of death was ruled “unknown trauma,” probably from a vehicle strike. But in the meantime, Hynes has seen other birds come in that did suffer from lead poisoning. It happens every year. “It’s kind of disheartening to see,” Hynes said.

Simple actions like choosing alternatives to lead ammunition and taking care to keep contamination out of the ecosystem can help prevent these unnecessary poisonings, Schuler said.

“We shouldn’t be killing these animals,” she added. “This is a totally preventable source of mortality, based on how we choose to exist in our environment.”

Want to learn more about lead ammunition and fishing tackle impacts on wildlife? See our investigative series, Misled on lead: The campaign to keep toxic lead in hunting ammo and fishing tackle.

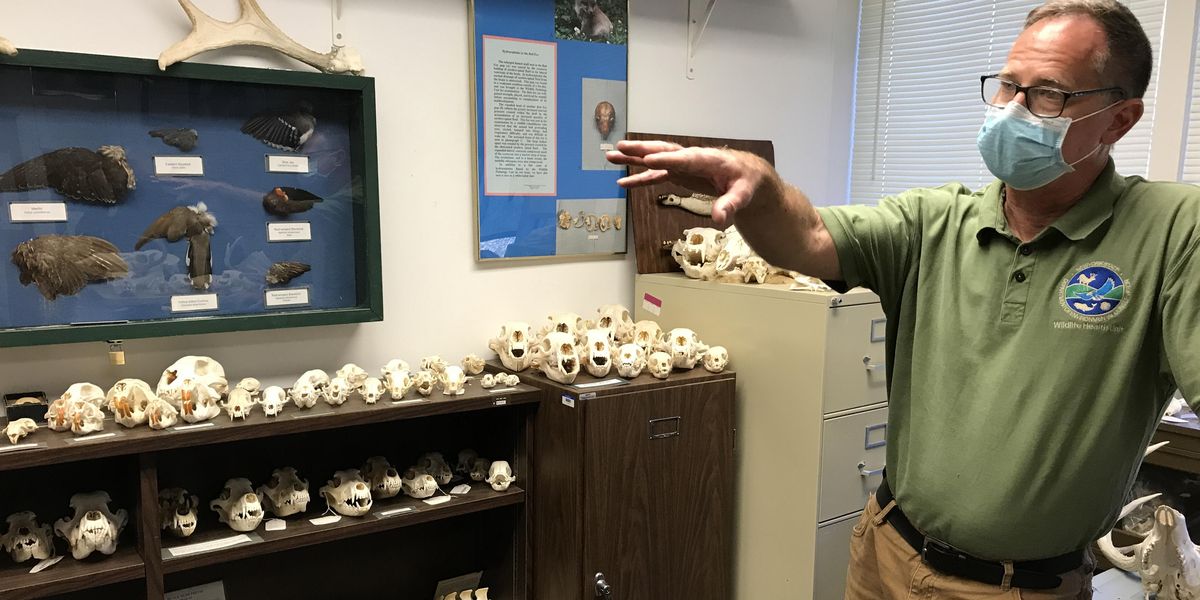

Banner photo: Kevin Hynes, a wildlife biologist with the New York Department of Environmental Conservation. (Credit: NYSDEC)