Many years ago, endocrinologist and medical doctor Robert Lustig had a patient, a 5-year-old girl, who was suffering from obesity. Unable to determine the cause of her obesity, Lustig scanned her for tumors.

The culprit was not a tumor, nor the girl’s diet, exercise, or family history. Rather, it was her body wash, said Lustig,a professor emeritus of Pediatrics, Division of Endocrinology at the University of California, San Francisco. A Victoria’s Secret bath gel, labeled “For Adults Only,” had been the source of a chemical — phytoestrogen — in the girl’s blood known to spur obesity.

Phytoestrogen is found in plants and acts on the body’s estrogen receptors, which induces the production of fat cells. It’s one of a class of chemicals referred to as obesogens, according to a set of new reviews published last month in the journal Biochemical Pharmacology.

As obesity rates rise in the U.S., scientists are working to understand what’s driving the epidemic. While diet and exercise are major factors, these reviews point toward obesogens as another important but under-studied contributor. The three reviews, which cover what obesogens are, how they cause obesity, and methods for studying them, point out how paying attention to obesogens can help shift focus in obesity research from treatment to prevention. Scientists also call for a reduction in exposure to obesogens, which are ubiquitous in everyday life, as a method to slow the obesity epidemic.

“They’re pretty much everywhere,” Jerry Heindel, a biochemist, founder and director of HEEDS, and lead author on one of the reviews told EHN. “Pretty much everybody is going to [be exposed to] some of these obesogens.”

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals

Obesogens are a subset of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, which disrupt a body’s hormone activity. Obesogens are generally defined as any chemical that can cause the human body to produce more fat than it normally would. These can include substances we usually think of as fattening, like sugars or artificial sweeteners.

However, many obesogens are not found in food, rather entering the body through other consumer products, like makeup, shampoos, soaps, plastics, and cleaners. Obesogens can also get into food from pesticides and food packaging. The chemicals are shed from such products and can accumulate in household dust, which people breathe in. PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (toxic chemicals used in many consumer and industrial products) are another example of obesogens, as is bisphenol- A (BPA).

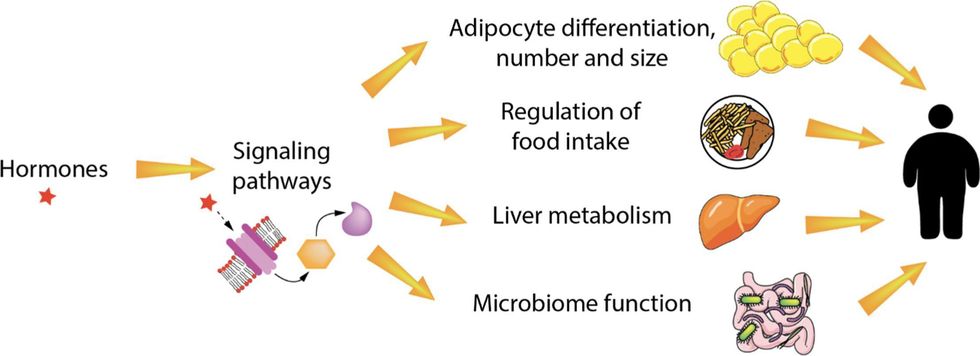

Obesogens can act on the body in many different ways. For example, said Heindel, different obesogens can disrupt metabolism, cause the body to produce new fat cells, alter our eating behavior, and even disrupt the gastrointestinal tract and the way food is digested.

Obesity levels

In the U.S., obesity has risen steadily over the past decades, from 30% of adults in 2000 to 42% of adults in 2018. Obesity in children has risen as well, from 14% in 2000 to 19% in 2019. People think about obesity mostly in the context of calories—if you eat more calories than you burn, you’ll gain weight. To deal with obesity, many clinicians will advise reducing the number of calories eaten and increasing exercise.

Diet and exercise undoubtedly play a major role in obesity levels. However, the persistent rise in obesity in the U.S. indicates to Heindel that something besides diet and exercise is at play.

But with the lack of available tests to determine whether a person might be suffering from obesogen exposure or not, scientists are still unsure of the role that obesogens play in proportion to other factors like diet and exercise. “There are so many multiple different factors going on, that we can’t pinpoint which one is doing what,” said Heindel.

Related: BPA—what you need to know

Doctors and healthcare workers, he added, are “focused on the fact that obesity is due to over-eating. So if you are obese, you can take drugs, you can be on a diet, or you can have surgery. And that’s supposed to take care of the obesity.”

Bruce Blumberg, a professor of developmental biology at the University of California, Irvine and an author on the reviews, agrees. “That’s still the view of the medical community, that obesity really has everything to do with calories and activity and not much to do with anything else,” he told EHN.

The Centers for Disease Control, for example, does not list obesogens as a driver of obesity; instead, it lists diet, activity, sleep, and genetics.

Ryan Baldwin, a spokesperson for the American Chemistry Council, an organization representing more than 190 chemical companies, pushed back against the new reviews.

“The prevailing view among the mainstream medical community is that obesity results from an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure caused by poor nutritional choices and insufficient exercise,” he wrote in a statement to EHN. “The evidence to support this view is much larger and of much higher quality compared to the evidence cited by Heindel [and co-authors] to support their obesogen hypothesis.”

Who’s most vulnerable?

While exposure to obesogens as an adult can cause weight gain, there are specific periods in development when people are most susceptible to obesogen exposure. Exposure is a particularly important consideration for pregnant people, the review warns, as the chemicals can pass through the placenta and affect the development of a fetus’s metabolic system in utero. That exposed fetus will have a higher risk of obesity later in life.

Young children are also more vulnerable to obesogens. During early childhood, the metabolic system is still under development, and susceptible to chemical influences. The changes that these metabolic systems undergo in early childhood — such as obesogen exposure — are carried through to adulthood, putting the child at a higher risk of obesity.

Avoiding obesogens

Individuals can reduce their exposure by avoiding pre-packaged or processed foods, which often come in containers made with obesogens like PFAS or other plastic additives. Avoiding fruits and vegetables treated with pesticides, or washing produce that has been sprayed, is another way to reduce exposure.

The authors of the reviews urge that obesogen exposure is such a widespread public health problem that it should be dealt with through regulation. For example, said Lustig, the Environmental Protection Agency should take responsibility for testing for and regulating such chemicals. That’s not happening, said Blumberg, because of a lack of will and funding within the EPA. “The EPA is heavily influenced by the industries that are regulated … that’s not the way they’re supposed to work,” he said.

Regardless, said Heindel, “it’s hurting peoples’ health, and hopefully [governments] will pay attention to that and act accordingly.”

Banner photo credit: i yunmai/Unsplash