PITTSBURGH—Last month, Pennsylvania took a major step toward joining the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a program that limits climate-warming carbon dioxide emissions from power plants.

The program, already implemented in Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia, has an important side benefit: lower emissions of other air pollutants that are harmful to human health, including sulfur oxide, nitrogen oxides, and fine particulate matter (PM2.5). RGGI only specifically regulates carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, but emissions of these other pollutants are reduced as a natural side effect of cutting CO2.

A 2020 Columbia University study found that those reductions helped RGGI states avoid an estimated 537 cases of child asthma, 112 preterm births, 98 cases of autism spectrum disorder, and 56 cases of low birthweight from 2009 to 2014, creating economic savings of between $191 million to $350 million.

Related — Fractured: The body burden of living near fracking

Pittsburgh has some of the worst air quality in the country, and childhood asthma is an epidemic. Up to 22% of kids in the region’s most polluted neighborhoods have asthma—more than double the state rate of 10% and the national rate of 8%.

RGGI (often pronounced “Reggie”) only regulates emissions from power plants, so it won’t reduce emissions from other major sources of air pollution in the region, such as U.S. Steel’s Clairton Coke Works and Edgar Thomson Plant, PPG Industries, and Harsco Metals. And Republican policymakers and industry groups remain opposed to RGGI, citing concerns that it may hurt communities that rely on the coal industry or raise electricity bills.

But, as the state eyes a 2022 entry into RGGI, experts say the program could have a major positive impact on children’s health in southwestern Pennsylvania and bring economic gains from avoided climate impacts and hospital visits.

“Air pollution doesn’t respect state lines or any kind of border, and a lot of what kids are exposed to is generated outside of their immediate area,” Frederica Perera, professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia Mailman School who led the 2020 study on RGGI and children’s health, told EHN. So even for children who live near other polluting facilities, Perera said, “there certainly would be benefits from RGGI.”

Air pollution and children

In addition to housing numerous polluting industrial facilities, western Pennsylvania is also home to four of the state’s six remaining coal-fired power plants—Keystone Generating Station in Armstrong County, the Conemaugh and Homer City Generating Stations in Indiana County, and Cheswick Generating Station in Allegheny County—which have the highest levels of toxic and climate-warming emissions compared to other energy sources.

Coal-fired power plants across the country have been closing as cleaner sources of energy become cheaper. As recently as 2005, Pennsylvania was home to 40 coal-fired power plants. Cheswick Generating Station, the plant closest to Pittsburgh, which has a long history of violating clean air laws, is expected to retire on April 1, 2022.

“Pennsylvania has the fifth dirtiest power sector in the nation and those three remaining power plants are among the top greenhouse gas emitters, so when you talk about putting caps on carbon dioxide emissions [through RGGI], the plants in this region are going to be a huge part of that conversation,” Vanessa Lynch, a Pittsburgh-based organizer with the environmental health advocacy group Moms Clean Air Force, told EHN.

Lynch noted that Pennsylvania has the tenth highest rate of childhood asthma among all U.S. states.

“Those rates are heavily impacted by pollutants coming from fossil-fueled power plants,” she said. Lynch has two teenage kids and said it’s frustrating how often it’s not safe for them to spend time outdoors because of poor air quality. “I’ve been pushing for the state to join RGGI because it will have a significant positive impact on the air our kids breathe.”

Asthma is more than an inconvenience—the disease caused hundreds of hospitalizations and more than 100 deaths in Pennsylvania in 2020. Nationally, asthma is the leading cause of absenteeism among elementary school students, contributing to developmental delays that can impact kids’ ability to succeed for a lifetime.

Lynch also noted that those facilities are among the state’s top emitters of sulfur oxide and nitrogen oxides. These compounds can cause decreased lung function and increased risk of respiratory diseases like asthma and COPD, and they also contribute to the formation of PM2.5 particles and ground level ozone, which are linked to a broad range of negative health impacts including cancer, heart disease, autism risk, and birth defects.

While kids near the fence lines of polluting facilities like the Clairton Coke Works will still be subject to localized emissions, they’ll likely still breathe cleaner air if RGGI results in a drastic reduction of harmful emissions in the state as a whole and in southwest Pennsylvania specifically.

Jamar Thrasher, a spokesperson for the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP), said the agency did not analyze region-specific benefits of the program, but its power sector modeling indicates that by 2025 the state’s remaining coal-fired power plants will have shut down.

“The communities surrounding those plants can expect to see air quality improvements based on the elimination of emissions specifically from those plants,” Thrasher told EHN.

The PA DEP has estimated that at the state-wide level, by 2030, joining RGGI will result in:

- 45,299 fewer asthma exacerbations in kids ages 6-18;

- 1,000+ fewer cases of acute bronchitis in kids ages 8-12;

- 350+ fewer hospital admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory issues combined;

- 282-639 premature deaths;

- Public health benefits totaling up to $6.3 billion

Climate change progress

DEP also estimates RGGI participation will prevent between 97-227 million tons of CO2 emissions between 2022 and 2030, depending on energy demands.

States already participating in the program have reduced their annual CO2 emissions from the power sector to 48% below 2005 levels, exceeding original goals. They’re expected to reduce these emissions by an additional 30% by 2030, and have already seen a net economic benefit of $4.7 billion.

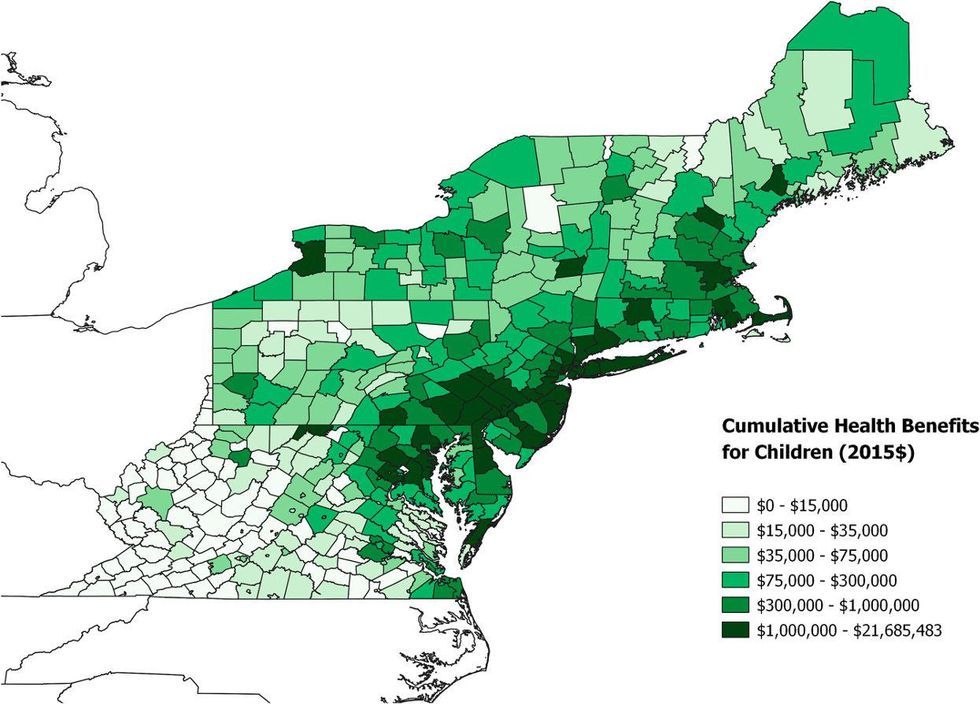

Because emissions travel, southwest Pennsylvania has already seen benefits from surrounding states participating in RGGI. According to the study conducted by Perera and her colleagues, Allegheny County has saved between $300,000 and $1 million in cumulative health benefits for children as a result of RGGI in surrounding states.

Conversely, a separate 2020 study found that Pennsylvania has the most premature deaths caused by air pollution per capita of any state, and that air pollution generated in Pennsylvania was also responsible for 306 premature deaths in Maryland, 715 in New Jersey, and 657 in New York.

“States that benefited from neighboring states joining RGGI are free riders in a way,” Perrera said. “Along with the health benefits, the PA DEP estimates an increase in gross state product of nearly $2 billion and an increase of over 30,000 jobs in the Commonwealth. So that’s a pretty substantial economic benefit in addition to what the state already saw from riding along on the actions of neighboring states.”

Environmental injustice implications

Perera cautioned that despite all of its benefits, “RGGI has not been an unmitigated success.”

She pointed to one study showing that under California’s cap-and-trade program, which is similar to RGGI, some power plants actually increased their emissions—and those plants tended to be located in environmental justice communities. Environmental justice communities are low-income communities and communities of color, which often face disproportionately high levels of pollution. The state of Pennsyvlania defines environmental justice communities as any census tract where 20% or more of the population lives at or below the federal poverty line, and/or 30% or more of the population identifies as non-white.

State agencies in California dispute that study, but research on RGGI in eastern states has documented a similar pattern, finding that 29% of facilities regulated under the program continued to increase emissions after RGGI was implemented, and that those facilities were usually in environmental justice communities.

DEP spokesperson Jamar Thrasher said that neither DEP’s modeling nor modeling conducted by researchers at Penn State University indicate that this is likely to occur in Pennsylvania.

“While we do not anticipate this to occur,” Thrasher told EHN, “We understand that there is a concern regarding the potential, which is why we committed to the annual air quality impacts assessment—to monitor for such an issue and respond accordingly.”

Those annual assessments, which were added during the final phases of DEP’s RGGI planning, will require DEP to review and publish emissions each year so that if this does occur, the state can take actions aimed at curbing those emissions. In response to public comments, DEP also added “equity principals” to its RGGI rules, which prioritize gathering input from the public, mitigating any adverse impacts to human health especially in environmental justice communities, and striving for equitable distribution of the program’s proceeds.

Economic benefits

Under RGGI, pollution limits on carbon dioxide become stricter over time. If power plants of a certain size are unable to stay below the limits they can purchase allowances, which both provides the state with funding and incentivizes cleaner, cheaper sources of energy. In Pennsylvania, it’s estimated that RGGI will generate $300 million a year from these fees.

“The proceeds from RGGI have been devoted significantly to communities that are hardest hit by air pollution [in states already participating in the program],” Perera said. “So that’s another potential benefit for these frontline communities.”

It hasn’t yet been decided how the proceeds of RGGI would be spent in Pennsylvania, but advocates of RGGI are pushing for the benefits to go to environmental justice communities. During a public comment period, a majority of the comments urged investment in these communities.

Gov. Wolf and Democratic legislators introduced legislation that would allocate the funds to communities affected by climate change, clean energy and energy efficiency initiatives, communities impacted by the transition away from fossil fuels, and environmental justice communities. If that law fails to pass—which is likely while the legislature remains Republican-controlled—RGGI’s proceeds will go into the state’s Clean Air Fund, and the legislature will vote to determine how it’s spent.

Opposition to RGGI

There’s a network of business groups and Republican lawmakers in Pennsylvania that have fought to stop RGGI from moving forward.

Many of these organizations and individuals

have ties to conservative think tanks that receive funding from fossil fuel companies and actively promote climate change denial.

One group without any known, direct ties to those organizations is the PA Chamber of Business and Industry, has cited a number of specific complaints about the way Pennsylvania RGGI is being set up.

“We generally support market-based programs as being more efficient in delivering environmental gains,” Kevin Sunday, director of Government Affairs at the PA Chamber of Business and Industry, told EHN. According to

its website, nearly 10,000 businesses are members of the organization, which lobbies for business growth in the state.

Power map produced at LittleSis.org

Sunday said his organization is concerned that other states that share Pennsylvania’s power grid won’t be included in RGGI. Power plants across 13 states share pooled energy through a transmission network called PJM, which stands for Pennsylvania, [New] Jersey, and Maryland (the first three states to join the network). Other states include Delaware, Ohio, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, West Virginia, Indiana, Michigan, and Illinois.

He pointed to

modeling conducted by PJM that suggests that if Pennsylvania joins RGGI, power generation might just shift to non-RGGI, coal-heavy states like West Virginia and Ohio. DEP’s modeling predicts that even if this occurs, it would have “no bearing on the environmental, health or economic benefits” of the program—an assessment Sunday said his organization disagrees with.

The PA Chamber of Business and Industry also disagrees with the way the DEP defines certain types of power plants to determine whether they’re subject to RGGI, thinks the state should have an option to leave the program in the future, and questions whether the public health benefits DEP is projecting under RGGI would occur even without the program since coal-fired power plants are already closing as a result of market pressure.

A number of Republican lawmakers have put out statements opposing Pennsylvania joining RGGI, including State Sen. Gene Yaw, who chairs the Senate Environmental Resources and Energy Committee.

“RGGI is a superficial fix, at best,” Yaw said in a press release. “It does very little to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, moves electric generation to Ohio and West Virginia, all while putting hardworking Pennsylvanians out of work.”

What’s next for RGGI in PA?

Now that the Pennsylvania Environmental Quality Board has approved the final rules for RGGI, The Wolf administration hopes to join the program in early 2022—but there are still a few hurdles.

The Independent Regulatory Review Commission, which has a board of three Democratic and two Republican appointees, is currently reviewing RGGi to determine whether it is “in the public interest” as defined by state law.

The Attorney General’s office is also reviewing the final RGGI rules to determine whether they comply with existing laws.

There could also be legal challenges. Last year, Republican state lawmakers filed a bill that would have required legislative approval to join RGGI, which was vetoed by Gov. Wolf. Republicans have promised a similar bill again this fall.

“The most important thing to me when I think about programs like RGGI are the impacts to families and children,” Lynch, the Moms Clean Air Force organizer, said. “It’s easy to talk about industry and supporting businesses, but in that process I think sometimes we forget about everyday experiences of those of us who live next to industrial processes.”

Banner photo: A Pittsburgh Climate Strike in 2019. (Credit: Connor Mulvaney for EHN)