“Young people are recognizing that the issues that we’re inheriting are ours now. Like, the inheritance process just got significantly shorter because of COVID.”

Prin, a college student and food justice advocate, tells me this as we sit on a bright orange bench at Sankofa Community Farm in Philadelphia. She says the work she does on the farm to support Black food sovereignty was “essential” before the pandemic, and will always be essential. Communities of color, like hers, already faced systemic health and environmental injustices that are only exacerbated by COVID-19.

Still, Prin says, the pandemic has spurred a renewed sense of urgency. Young people are “stepping up to do their part with their families,” especially now that everyone is home. More of her friends are asking her about how growing food is connected to social justice and environmental sustainability, which, she says with a smile, is good for her YouTube channel as well as the planet.

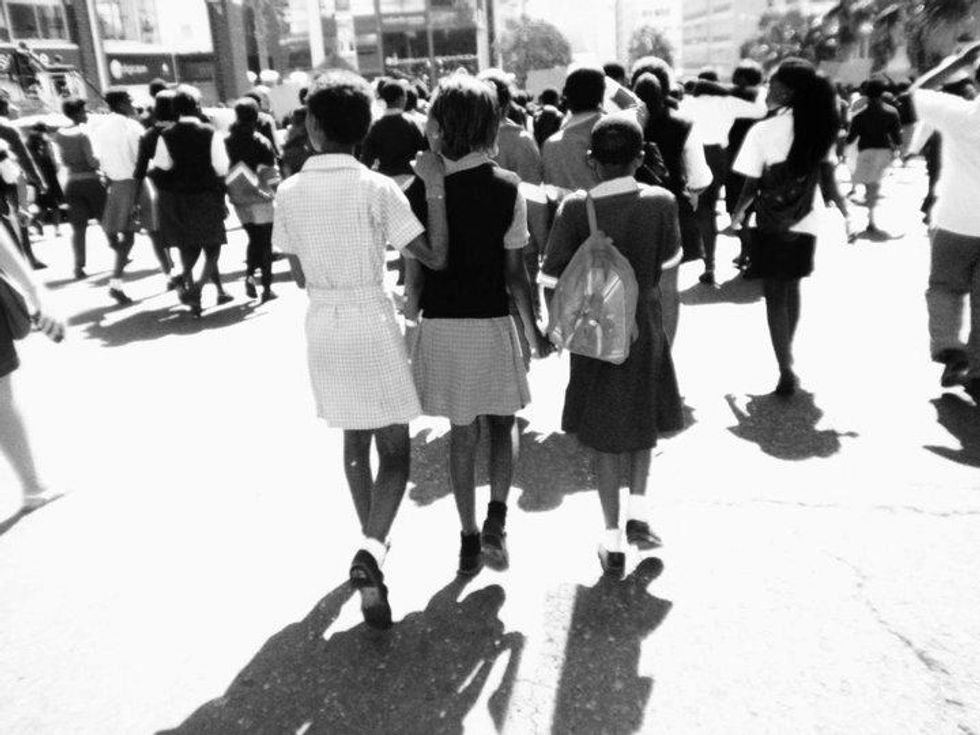

Prin is part of a generation of young people motivated to make sure they have a future to lead. Like the four million young people who took to the streets for the Climate Strikes, Prin is working to secure a healthier, safer, and more just future for herself and her community.

This essay is part of “Agents of Change” — see the full series

Yet, to what extent should young people shoulder this burden?

A hyper-focus on the agency of young people can place unnecessary pressure on a group that already faces significant challenges due to high risks of experiencing food insecurity, poverty, mental health challenges, environmental health hazards, and “climate anxiety.” Educators and researchers like myself are concerned not only about future harm as a result of climate change, but also about present stressors that may cause permanent damage during a developmentally critical time in young people’s lives.

So, as we talk, I ask Prin how she engages with the family and community that support her. “Like, through jokes” she says. She laughs and remembers wise cracks people made at family get-togethers, like “if everything on your plate is the same color, you’re doing something wrong.”

Despite best efforts, families that look like Prin’s continue to suffer from higher rates of food insecurity in the U.S. regardless of whether general population levels go up or down. In addition, the paradox of simultaneous increases in both global hunger and global obesity rates disproportionately affect communities of color who are more likely to be exposed to pollution from industrial food production, more likely to be exploited in the food systems labor force, and less likely to be able to afford nourishing foods as prices rise. Addressing these systemic inequities requires more than just teaching people to “eat healthy.”

This essay is also available in Spanish

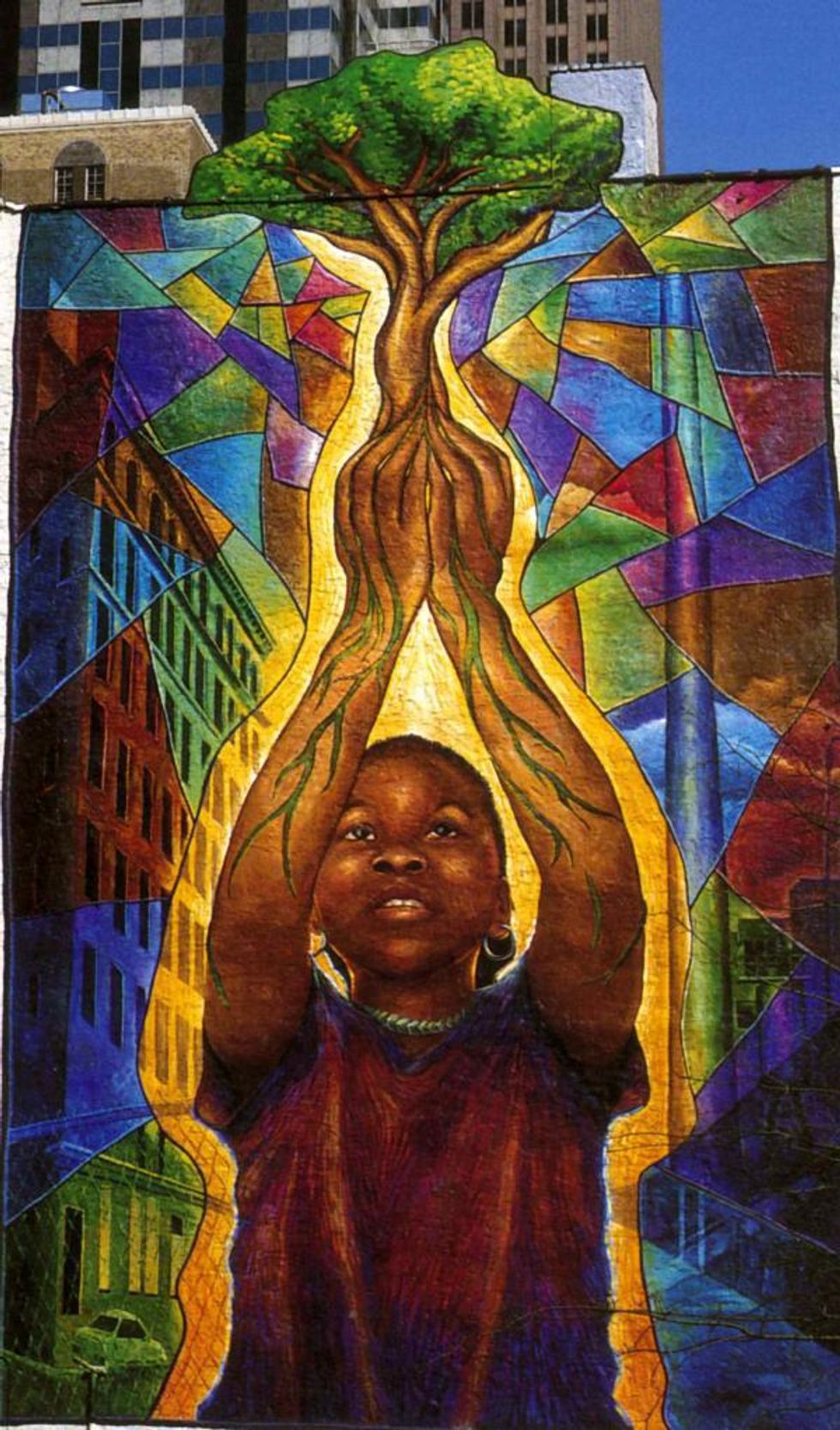

Prin came to the farm to learn more about a history of food and land in this country that made it so that there were “like four or five corner stores” on her path to school when she was a child, even though she only lived 10 minutes away. Through her work on the farm, however, she is learning not just about the problems her generation is “inheriting,” but also about the tools and resources that those who came before her left behind.

Shoulders of giants

Omodé gbón Àgbà gbón L’afi dá Ilé-ifè: the wisdom of the young and the wisdom of the old are the core of Ilé-ifè (Creation)-Yoruba Proverb

Prin is one of many young people I have worked with over the years, building creative and civic engagement initiatives to promote community and environmental health. My current doctoral work focuses on how young people (de)construct, interpret and share oral and written texts as they work toward food and environmental justice in their communities. This work is influenced by extensive contributions from literacy scholars like Dr. Vivian L. Gadsden and Dr. Gerald Campano. They highlight, among other aspects, the importance of engaging families as co-constructors of research and educational processes, and of building intergenerational coalitions to address social injustices.

Studies have shown that young people are more engaged in learning when communities and families are involved. These approaches can also help address the inequities baked into our education system, stemming from concerted disinvestment and discriminatory practices that simultaneously create dependence and strip resources from low-income communities and communities of color. Family and community engagement also helps to make visible the levers needed to improve students’ social-emotional functioning and literacy and math learning.

As rates of homeschooling and distance learning increase due to the pandemic, understanding how young people work with their communities to build on ancestral knowledge can be an important step toward ensuring a more just and sustainable future.

Building intergenerational coalitions

Simply being in intergenerational spaces does not automatically result in intergenerational learning, just like being in a classroom does not automatically result in learning. Efforts to promote intergenerational learning would explicitly aim to promote greater understanding and respect between generations, and would dedicate the time and resources needed to meet this aim. My work thus far has prompted me to center the following questions when thinking about building intergenerational coalitions:

- What is already known and understood? I take heed from Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, who reminds us in Braiding Sweetgrass that “doing science with awe and humility is a powerful act of reciprocity.” For me, this means partnering with community-based organizations like the Southwest and West Agricultural Group to design research questions that are relevant to their work with young people. It means mapping out converging and diverging goals, interests, and methods in these collaborations, and it means remembering that just because knowledge isn’t expressed in ways that might be recognizable to me, doesn’t mean it is not there.

- How are different modes of expression used to activate ancestral knowledge? For me, it’s through dance. West African dance, more specifically, has been an important aspect of my experience with intergenerational learning and food justice, as many of the dances stem from food cultivation and preparation practices. In History Dances, Dr. Ofosuwa Abiola highlights the ways in which natural body movements of everyday tasks, like farming, cooking, and harvesting, helped to inform Mandinka dance systems and even modern West African dance vocabulary. When I dance, there is space for my whole self (body, spirit, mind, emotion) in the merging of movements informed by my unique experiences with movements inspired by the traditional knowledge archived through the dances. The energy that propelled my ancestors to grow, nurture, cultivate, resist, persist, and share are in these movements. I give thanks, and try to pass that energy onwards in my teaching, in my research, in my writing, and in my movement.

- How can tension be productive? Asking people to step into their past can be discomforting, but it can also help to deepen the learning experience. When encouraging my students on the Navajo Reservation to pursue their goal of writing a bilingual, Navajo-English play, a parent asked that I instead focus on teaching English to better prepare students for colleges and careers that privilege English. This parent’s concerns were valid and not uncommon amongst older generations of community members; especially those who had lived through the Indian Boarding School era and who had been told for decades that their language and culture had no value. This is not unlike the experiences of some of the youth I now work with at the farm. They have community members who do not see the return of youth of color to the land as desirable. Rather, they see it as a reminder of this country’s exploitation of Black and Brown bodies in the pursuit of agricultural and economic gains, and as a regression to a lifestyle that many elders fought to be free of. These are the sorts of tensions that invite us to face ruptures in our past so that they don’t persist in our future.

Ensuring accountability

As co-director of Sankofa Farm, Chris Bolden-Newsome, notes “to get our healing, we have to return back to the scene of the crime.” Whether the “crime” took place on agricultural land, or in language and literacy classrooms, often the communities that suffer most from the lingering effects are not the perpetrators and should not be held solely responsible for rectifying the situation. Despite the power of intergenerational collective action, community-based coalitions cannot do this work on their own. It is incumbent upon policy and decision makers to support this work.

Youth leaders like Prin aren’t just asking to be heard, they’re asking for today’s leaders to act in a way that won’t make their efforts obsolete. As we think about how best to support them, it’s important that we uplift young people’s contributions to intergenerational efforts, as well as hold policy and decision makers accountable for ensuring intergenerational environmental justice and health equity.

When it comes to coalitions for environmental justice, advocating for legislation that sustains and protects ancestral knowledge and land, and that provides resources and infrastructure for young people to build on these platforms, are important steps.

Prin is working towards this future; “Like, my story…if I told it more and I got more attention on the issue, more funding to these social programs, more students will be able to be on the farm and get funded. And I just feel like this immense responsibility to do my part.”

Young people all over the world are taking on these immense responsibilities. We need policies and programming that take their stories seriously and that strengthen the intergenerational coalitions that support them.

OreOluwa Badaki is a Ph.D. Candidate in in the Literacy, Culture, and International Education Division at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education. OreOluwa also serves as Co-Director for the Collective for Advancing Multimodal Research Arts at the University of Pennsylvania, and as a lead researcher with the Southwest and West Agricultural Group in Philadelphia. She can be reached at obadaki@upenn.edu.

This essay is part of “Agents of Change,” an ongoing series featuring the stories, analyses and perspectives of next generation environmental health leaders who come from historically under-represented backgrounds in science and academia. Essays in the series reflect the views of the authors and not that of EHN.org or The George Washington University.

Banner photo: Young students in Navajo, New Mexico, signing a banner made by older students to promote cultural awareness and environmental consciousness. (Credit: OreOluwa Badaki)