Particulate matter pollution emitted by Pennsylvania’s fracking wells killed about 20 people between 2010 and 2017, according to a soon-to-be-published study.

Pennsylvania is the second-largest producer of natural gas in the U.S. after Texas. Between 2010 and 2017, there were 20,677 permitted fracking wells in the state, about half of which had been drilled. Fracking, another name for hydraulic fracturing, is a process of extracting oil and gas from the Earth by drilling deep wells and injecting liquid at high pressure.

One of fracking’s byproducts is particulate matter pollution, also referred to as PM 2.5, which consists of tiny, airborne particles of chemicals that, when inhaled, make their way into the lungs and bloodstream, increasing cancer risk and causing heart and respiratory problems. Exposure to PM 2.5 kills an estimated 20,000 Americans each year.

Previous studies have found that heavily-fracked communities face higher rates of numerous health effects including preterm births, high-risk pregnancies, asthma, and cardiovascular disease—but this is the first to investigate the direct relationship between the local increase in PM 2.5 caused by fracking and deaths from respiratory and heart issues that can be attributed to that increase.

“Our study is not only looking at negative health outcomes, but investigating how fracking actually caused these deaths through increased air pollution,” Ruohao Zhang, a researcher at Binghamton University who specializes in environmental economics and the study’s lead author, told EHN.

Zhang and a team of four other researchers used satellite data from NASA to calculate daily PM 2.5 emissions from all fracking wells in the state over the seven-year period between 2010 and 2017. To determine how many people died as a result of exposure to those emissions, they used county-level mortality data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention paired with established methods for calculating how many of the deaths seen in Pennsylvania during that time period were caused by increases in PM 2.5 exposure.

“The levels of increased PM 2.5 concentrations that came from fracking wells in the state is associated with about 20 additional deaths during that time period,” Zhang said. These are deaths that presumably would not have occurred in the absence of air pollution from fracking. The estimated economic loss caused by these additional deaths is around $148 million, according to the study.

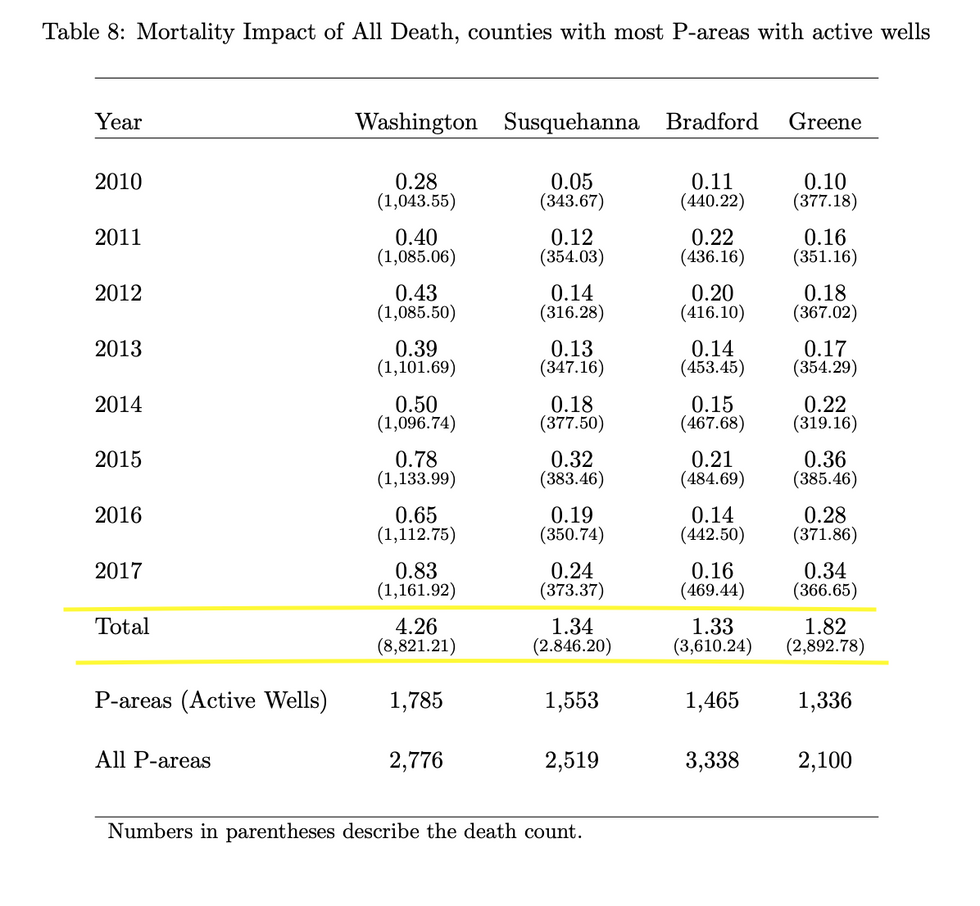

Washington County was the most heavily affected county in the state, with an additional 4.26 deaths caused by PM 2.5 emissions caused by fracking between 2010 and 2017.

“When we accounted for airborne spillover of pollution from multiple wells in the same area we found that, overall, fracking made the particulate matter pollution of a three-kilometer area around each well [roughly 1.8 miles] higher by between 1.27 percent and 5.67 percent,” Zhang said, explaining that the high end of that spectrum usually reflected a higher density of wells in the area.

While the increase in PM 2.5 was highest closest to the fracking wells, Zhang noted that increased levels of the pollutant were also detectable at least as far as 10 kilometers (about 6 miles) downwind of emission sources.

The study also found that without accounting for “spillover,” each individual well caused an increase in PM 2.5 in the surrounding three-kilometer area of between 1.35 percent and 2.19 percent. The higher end of that spectrum generally represents wells in the active drilling phase, while the lower end generally reflects the pollution caused by wells that are already up and running, or in the “production” phase.

The NASA satellite data the researchers used became available about two years ago. Without it, Zhang said, it would have been impossible to calculate the specific air pollution increase caused by fracking in the state due to a lack of continuous, on-the-ground air monitoring systems.

“In the U.S., air quality regulations are highly dependent on ground-based monitors, which only cover a small portion of the whole country,” Zhang said, noting that this is especially true in rural areas that tend to be home to lots of fracking. Even in places that are covered by ground monitors, he added, monitoring is rarely continuous—they often only take samples every six, eight, or 16 days.

“There are huge monitoring and data gaps there, allowing for what’s referred to as ‘unwatched pollution,’” Zhang said. “But this satellite data allows us to continuously monitor air quality everywhere.”

The NASA satellite data itself doesn’t directly relay air pollution data. Researchers like Zhang look at the degree to which aerosols in the air prevent the transmission of light to determine concentrations of PM 2.5. While this method has previously been used to estimate PM 2.5 levels across the globe or over specific countries or continents, Zhang said, it’s most accurate when used to calculate air pollution in a smaller area, such as a single state.

A resident of Washington County, Pennsylvania, points to fracking infrastructure near his home. (Credit: Kristina Marusic/EHN)

A resident of Washington County, Pennsylvania, points to fracking infrastructure near his home. (Credit: Kristina Marusic/EHN)

Based on their findings, Zhang said he would encourage local and state elected officials to regulate the shale gas industry to reduce PM 2.5 emissions and protect the health of residents. In the meantime, he said, people living near fracking wells who are concerned for their health can minimize the impacts of PM 2.5 exposure by keeping their windows closed and not exercising outdoors in close proximity to operational wells.

“I would also tell residents in Pennsylvania that if they learn they have shale gas under their property, they should be aware that their decision about whether or not to lease their land for drilling may impact not only their own health, but the health of their neighbors as well,” he added.

Zhang also pointed out that while their study focused on deaths caused by PM 2.5 pollution from fracking, fracking also generates many other kinds of pollution—such as volatile organic compounds and radioactive waste—that can endanger the health of residents and should be accounted for.

“We think it’s important to know how every kind of pollutant caused by fracking impacts human health,” he said. “We hope that future studies will help us more fully understand the impacts of fracking on local communities.”

Banner photo: A resident of Washington County, Pennsylvania and his son approach fracking equipment near their property. (Credit: Kristina Marusic/EHN)