Editor’s Note: This Q&A originally ran on The Harvard Gazette and is republished here with permission.

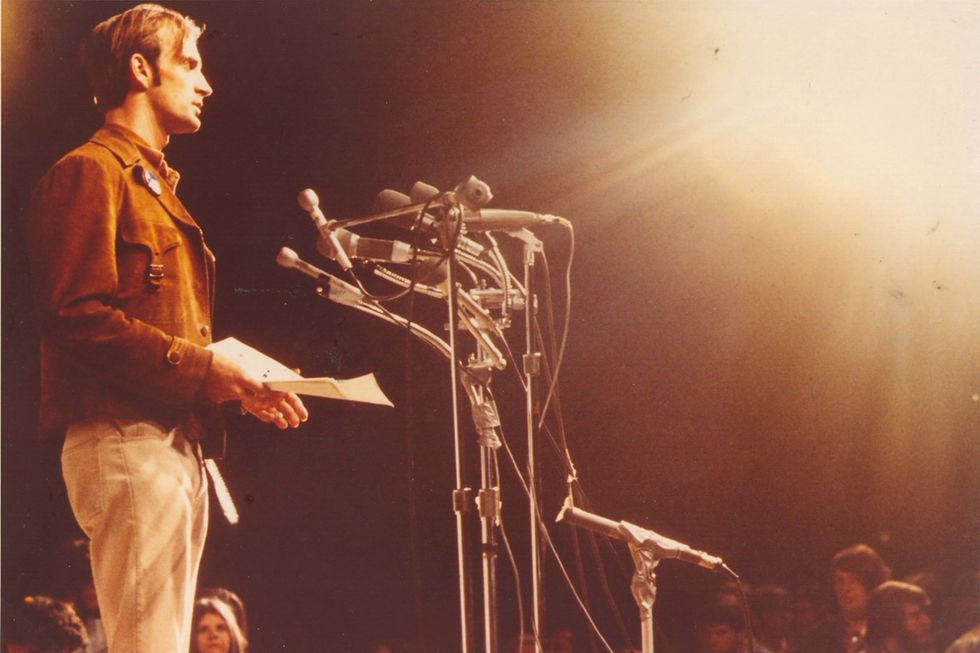

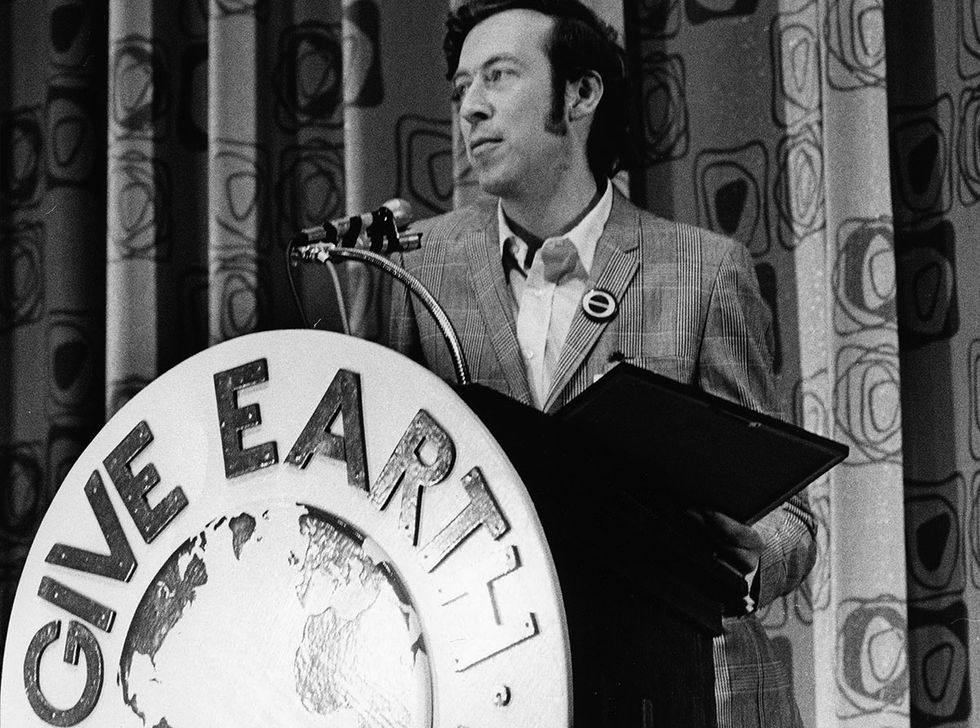

Denis Hayes was a 25-year-old student at Harvard Kennedy School in 1969 but dropped out after a semester to become a principal organizer of a grass-roots nonprofit that planned a nationwide rally on April 22, 1970, an event they would call Earth Day.

That one-day gathering to raise awareness of threats to the environment, held in hundreds of cities and towns across the country, attracted a reported 20 million people.

Now CEO of the Bullitt Foundation, a Seattle nonprofit that promotes and supports environmental and climate protection efforts in the Pacific Northwest, Hayes spoke with the Harvard Gazette for Earth Day’s 50th anniversary about the birth of the event, how he stumbled into a leadership role as a Kennedy School student, and Earth Day’s lasting influence on environmental policy.

How did you first become interested in environmentalism?

HAYES: When I grew up, in a [Washington state] paper-mill community, there was no form of pollution control on the smokestacks. The stench from sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide was pervasive.

The dominant image everybody had of my town for 25 miles in every direction was “that’s the place that stinks.”

The mill poured uncontrolled water pollution into the Columbia River.

Occasionally, we would go down there and come across massive fish kills. Paper, of course, is made from wood, and the logging was about as rapacious as it could be. I’d be out camping one summer in a beautiful place and go back the following summer, and it would be a moonscape.

When I was very young, all this didn’t really turn me into a rabid activist. But I did have this sense that, “My God, we should be able to create paper without destroying the world.”

You got into Harvard Law School, but deferred for a year and then wound up at Harvard Kennedy School in the fall of 1969. What brought you there?

HAYES: I took off after my sophomore year in college and went hitchhiking around the world for three years, sort of in search of myself. I wanted to see firsthand all of the different basic philosophies and economic systems in the world, looking for some unique contribution that I could make.

By the time I returned, I had decided that what I wanted to do with my life was to pursue ways to integrate the principles of ecology into human affairs. So I came back, finished up my undergraduate degree. It was the first year of the M.P.P. program at the Kennedy School.

The way they did it was to invite 12 university presidents to each nominate one student to this pilot class. Stanford nominated me.

I accepted because 1) I thought that there would be things taught there that I could profit from, and 2) just the honor.

Plus, candidly, Harvard provided some financial support and that was something that I really needed. So, all of those things came together.

Was there widespread interest in environmental issues at Harvard then, or were you hoping to be the one to bring that to the forefront?

HAYES: We had a war going on in Southeast Asia and the Civil Rights Movement had moved to a new state of black nationalism.

The environment was not, at that point, a college issue, certainly not in Cambridge, but really, not much anyplace. I didn’t view myself as a person who was trying to bring that to Harvard particularly—at least, not when I arrived.

There was a senator from Wisconsin, Gaylord Nelson, who had an intuitive, political belief that the time was right for environmental issues to start achieving a higher degree of political traction in the country. Gaylord thought that progress was actually leading to a degradation in our standard of living, and that a hidden anger was building up.

We’ve kind of forgotten now, but the air in Gary, Ind., in Pittsburgh, in Los Angeles then, was like the air in Shenzhen or New Delhi or Mexico City today.

He saw rivers catching fire, lots of bird species (including the bald eagle) endangered, the Santa Barbara oil spill, urban freeways slashing through vibrant inner-city neighborhoods, and he concluded that the issue was ripe, even though nobody was speaking of it.

He started giving speeches calling for campus “teach-ins” on the environment.

And precisely because I hadn’t heard anything about the environment, I thought, maybe I could organize Harvard if no one else was already doing it.

So why was your tenure at Harvard so short?

HAYES: With the audacity of youth, I flew down to Washington, D.C., for a 15-minute courtesy interview with the senator. It turned into a more than two-hour talk about how to try to get such a campaign organized. We talked about what one might do, and I returned with a charter to organize all of Boston.

And then, a couple of days later, I had a call from his chief of staff asking whether I would drop out [of Harvard Kennedy School] and come down to organize the United States.

Within a week of my conversation with the senator, I was packing up and leaving for Washington, D.C.

What did environmental activism look like at that time?

HAYES: Candidly, there wasn’t much activism around “the environment” as an issue.

The real situation in the 1960s is that there were people who cared about birds in the Audubon Society and the Environmental Defense Fund.

There were people who lived in Santa Barbara who cared about oil spills, or lived in Gary, Ind., and cared about air pollution. There were anti-freeway coalitions in a dozen cities. But all of these groups, and dozens of others, thought of themselves as freeway groups, as air pollution groups, as bird groups.

One of the most important things—I think the most important thing—that Earth Day did was to take all of those different threads and weave them together into this fabric of modern environmentalism, to help them understand that they were operating from similar sets of values and then that they could support one another and be much stronger as a whole than they were individually.

I remember this one passionate conversation with the then-president of the Audubon Society. He basically said, “What the hell does clean air have to do with birds?”

After Earth Day, nobody would say something that absurd.

When you left Harvard Kennedy School for this fledgling organization in D.C. as one of Earth Day’s very few full-time paid staffers, your charge was to do what exactly?

HAYES: Senator Nelson turned out to be absolutely right: The country was very ripe and ready for something like this. But campus teach-ins turned out not to be the place to start. The first thing that we did was find some regional organizers and send them out to colleges across the country.

This was all starting the first week in January [1970].

And everybody came back after a week or two and said, “This is like running into a brick wall. This is not something activist students care about.”

So we analyzed the mail that had come into Nelson’s office as a result of press coverage of his speeches.

Overwhelmingly, it was from women, mostly they were 25 to 35, mostly college-educated, mothers of young children, mostly in single-wage-earner families, and they want to know what they could do to get involved.

By the end of January, we had changed the name from Environmental Teach-in to Earth Day and taken out a full-page ad in The New York Times announcing the change.

What else did you do to help get out the word?

HAYES: At that point, we were sending organizers out to talk to community organizations and civic groups across the country.

But a very big part of what we did was work with newspapers, with magazines, journals, with various associations to get information broadcast and into people’s hands.

Our biggest supporter by far was the United Auto Workers. We would have these floods of mail after we got something placed in a magazine. In the end, we got the United Auto Workers to start printing our newsletters for us and paying for our postage. We ultimately had about 60,000 names [on our mailing list].

We’d run the envelopes through the addressograph machine; the volunteers would stuff them with the newsletters, stamp them, and haul them off to the post office.

We didn’t have computers or cellphones; there was no internet or social media.

And until the last two months, we couldn’t even afford a 1-800 telephone line. We’d broadcast our messages, wait for interested people to respond, and then follow up with them.

Fortunately, some of those young women volunteers turned out to be world-class organizers.

When did everyone in the organization start to feel a momentum, or realize that maybe this was going to be bigger than you initially thought?

HAYES: We had some feelings of that as early as late February or early March, just because of the volume of mail that was coming in and the numbers of people who were signing up to become organizers. But it was difficult for us to tell until the event itself how real this would be.

The first time that I really knew was in New York City. On Earth Day, one of the places I went was a huge rally in Manhattan. Mayor [John] Lindsay had shut down Fifth Avenue, barricading the streets that would ordinarily pass through it, for Earth Day.

And I climbed up onto this speakers’ platform several stories high, and I could not see the end of the crowd. It stretched out for 40 or 50 city blocks.

It was like looking out at the ocean!

Though you ended up drawing big crowds in a number of cities, wouldn’t you agree that the one in New York City proved especially important for your organization?

HAYES: We thought we would be as big as a typical anti-war rally by the time we started getting optimistic. But what was different about Earth Day was, whereas the Vietnam Moratorium [demonstration on Oct. 15, 1969] was focused in perhaps six or eight cities, Earth Day was in basically every city, every town, every village, every crossroads in America.

Back then, The New York Times, Time, Newsweek, NBC, CBS, ABC, AP, UPI were all [based] in New York City, [so when] they look out their windows and see the crowd, and they’re getting [reports] in from all over the country and suddenly…this estimate that has now become the revealed wisdom of 20 million people, made it the largest organized event in the nation’s history.

In late 1969, had you asked the question, “What do you think about the environment?” I think the most common response would have been, “What is the environment?”

Maybe someone who had taken a psychology course would know, but it just didn’t have any kind of political connotation to it at all.

By midway through 1970, something like 80 percent of Americans said that they were environmentalists.

The Environmental Protection Act (EPA) was established in late 1970 and followed not long after by a slate of important environmental laws, like the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Water and Clean Air acts. What role did Earth Day play in the national policy debate and in the passage of those laws?

HAYES: When [aide to former President Richard Nixon] John Ehrlichman got out of the slammer, I was practicing law, and one of his sons was my paralegal. So John stopped by, and we all went out for dinner. According to him, with regard to the EPA, the effect was crystal clear.

Nixon, in setting off the Southern strategy to try to flip the conservative, racist, solidly Democratic South to the Republican Party, had put in peril a whole lot of Republican support from the Romneys, the Lindsays, the Scrantons, the McCloskeys, the Brookes, the Chafees—the progressive wing of the party.

Nixon was particularly worried about John Lindsay, who was everything that he was not: Lindsay was tall and handsome and rich, attractive to women.

So Ehrlichman says he’s there with the president and Nixon looks out at this very large crowd out on the Mall in Washington, D.C., and he looks at the television and sees a much larger crowd in New York where John Lindsay is addressing it.

And he said, “We gotta somehow become players in this.” According to Ehrlichman, he said to Nixon, “Remember that commission that you had on government organization that Roy Ash chaired for you? It proposed an environmental protection agency. And the beauty of it, Dick, is we’re already doing this stuff: Air pollution? We got that in Health, Education, and Welfare. Water pollution? That’s over in Interior. Radioactive waste? That’s with the Atomic Energy Commission. Pesticides? That’s over at the Department of Agriculture. You can take all of these things out of those departments, you stick them into an agency, you call it an EPA. You might even save a little bit of money and suddenly, you’re a player.”

And Ehrlichman says that, although the Executive Order wasn’t issued for several months thereafter, Earth Day was the day that Nixon decided to set up the Environmental Protection Agency.

So you had some political momentum at that point, but this was a time of widespread political and social upheaval and unrest. Washington was facing calls for various kinds of reform from a number of directions. How did you keep Earth Day from getting lost in the noise?

HAYES: We had this gigantic number of people out for Earth Day, which caught the attention of everybody. For a day, all things were environmental. But a few days later, Nixon invaded Cambodia and a couple days after that, the National Guard shot four students at Kent State. And the environment completely disappeared from the radar.

That fall, we launched a campaign against 12 members of Congress, incumbent congressmen who had bad records on the environment, who’d won their previous elections by a relatively narrow margin, who had an important environmental issue in their districts, and in whose districts we also had a good strong Earth Day organization.

With a very small budget, like $50,000, we launched this campaign against “The Dirty Dozen.” In the end, seven of the 12 were defeated, and more than the margin of victory was clearly made up by people who voted largely on the basis of their environmental record to throw them out. One of them was the chairman of the House Public Works Committee—that really got the attention of Congress.

The 1970 election was when Congress understood that Earth Day was not an anti-litter campaign where people went out in the park and danced around mulberry bushes.

The Clean Air Act was aggressively opposed by the coal industry, the electric utility industry, the oil industry, the automobile industry, the steel industry. The Clean Air Act passed the Senate on a voice vote unanimously and passed the House of Representatives with, I think, one dissenting vote. Congress was running scared over “The Dirty Dozen” campaign.

We carried the momentum from the overwhelming vote for clean air into lobbying campaigns for the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Toxic Substances Control Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, on and on.

What’s been the most heartening sign that Earth Day has made a meaningful difference in the world over the last 50 years?

HAYES: I think the widespread, almost universal respect for environmental values.

That paper mill that stunk beyond belief, that sent out those acids that ate through the roofs of houses and pitted the roofs of automobiles whenever it rained (and it rained all the time in Camas, Wash., a 5,000-person community on the Columbia River)—today, something like that would be literally inconceivable any place in the United States.

What was normal in 1969 became unthinkable in the early 1970s, and it has retained that. It’s strongest with regard to things that influence human health, and most of those laws have human health built right into them as what’s to be protected.

But it goes beyond that. It involves a respect for the diversity of life and the healthiness of the environment. And the need to protect this planet as our only home.

All of these things are now enshrined. I think, if one were to take a poll today, there would be stronger support for the proposition that Americans should have a constitutional right to a clean, healthy environment, than for most of the items in the actual Bill of Rights.

Pretty formidable change.

Interview has been edited for clarity and condensed for length.

Banner photo: Earth Day 1970 (Credit: University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability)