A climate change initiative in the Northeastern U.S. designed to cut greenhouse gas emissions has also greatly reduced harmful air pollution and related impacts to kids’ health, such as asthma, preterm births and low birth weights, according to a new study.

Led by researchers from the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, the study found the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative has reduced fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and, due to this reduction, the region avoided an estimated 537 cases of child asthma, 112 preterm births, 98 cases of autism spectrum disorder, and 56 cases of low birthweight from 2009 to 2014.

By avoiding such impacts to children’s health, the researchers estimate an economic savings of between $191 million to $350 million.

“Toxic air pollutants are released right along with [carbon dioxide],” lead author Frederica Perera, professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia Mailman School and director of translational research at Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health, told EHN. “Because of biological vulnerability, developing fetuses and young child are disproportionately affected by air pollution and climate change.”

PM2.5 consists of toxic airborne particles much tinier than the width of a human hair, and is linked to a variety of health impacts including respiratory and heart problems, birth impacts and altered brain development for children.

The microscopic pollution can be made up of many different particles, but in this study—published today in Environmental Health Perspectives— researchers looked at reductions in nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide, which, once emitted from power plants, react in the atmosphere to form PM2.5.

The estimates of health benefits and cost savings are likely conservative: atmospheric-formed PM2.5 is the majority of the particle pollution from power plants, however, there is also some directly emitted from the plants, which the researchers did not take into account. Nor did they look at other toxics such as ozone or nitrogen dioxide.

The calculated economic benefits also don’t consider the benefits of greenhouse gas emission reductions.

“These estimates of cost are definitely undereatimes, as they do not include the long term lifetime costs of these disorders or impairments,” Perera said.

“Preterm births, for example, raise the risk for respiratory illness in adulthood, and for cognitive effects like decreased IQ, so we can consider these conservative estimates,” she added.

Double-benefit

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative was established in 2005 and is the first of its kind in the U.S.

It’s an effort among Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey (which left the imitative in 2012 but returned in 2020), New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont—with each state expected to reduce their annual carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector by 45 percent below 2005 levels by 2020, and by an additional 30 percent by 2030.

It does so largely by placing limits on carbon dioxide from new and existing fossil fuel-using power plants with a minimum capacity of 25 megawatts—such plants must offset their emissions by buying allowances (for each short ton, 2,000 pounds, of carbon dioxide emitted) that are reinvested in renewable energy and energy efficiency.

It’s been successful: in 2017 the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative reported the states had already reduced carbon dioxide emissions by more than 50 percent since 2005.

As a side benefit of the initiative, levels of PM2.5, carbon monoxide, lead, ground-level ozone, nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide have decreased.

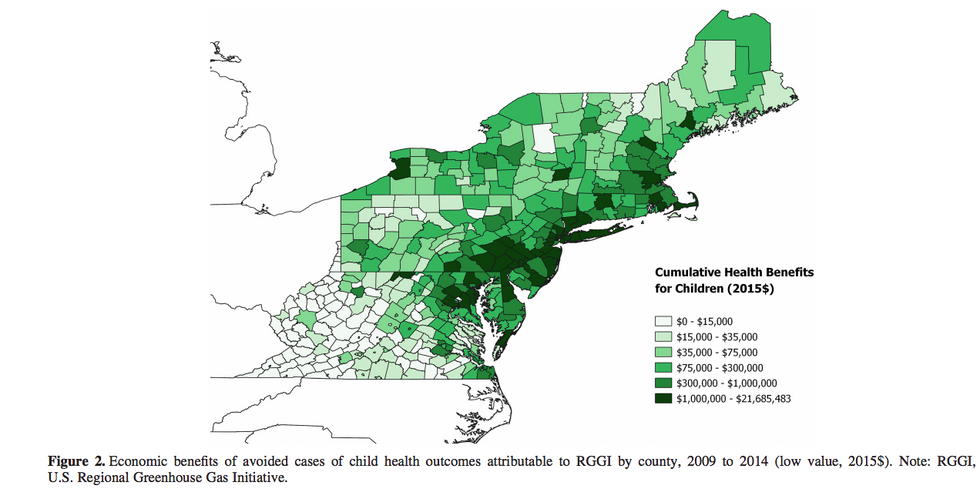

In the new study, the researchers used a tool from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that estimates air pollution-related illnesses and deaths and assigns an economic value. They looked at the states participating in the climate initiative as well as adjacent states (Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia.) The tool doesn’t track actual cases of illness, rather, models what the improvement in air quality would be given the emissions reductions, and then estimated reduced rates of illness and disorders.

The authors pointed out that “more densely populated areas would be expected to have higher benefits because there is a larger at-risk population (more pregnant women and children) breathing cleaner air.”

“This is likely occurring in densely populated counties across New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey,” they wrote.

This isn’t the first analysis to pin health benefits on the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative —in 2017, Abt Associates estimated that the total value of health benefits from the initiative from 2009 to 2014 were between $3 billion and $8.3 billion, with roughly 300 to 830 avoided premature adult deaths.

A “good news” story

The new study did have limitations—the link between PM2.5 and autism is likely given past research, however, hasn’t been proven. There is strong evidence that PM2.5 negatively affects children’s IQ, but the new review did not consider the “potentially large benefit” of the climate initiative in improvement of children’s IQ.

Perera said they were also unable to track health benefits by race or income level, as they would have needed finer, neighborhood level data. “We know these pollutants are major contributors to inequality worldwide, they disproportionately affect places where poverty and environmental injustice compound the effect,” Perera said.

Nonetheless, she said this is a good news story.

“We hope the results will spur policymakers when designing these policies to consider the health benefits to children and how to maximize those,” she said.

Banner photo: Children playing at the Maine Botanical Gardens in 2019. (Credit: Michele Dorsey Walfred/flickr)